When Jeff Rose was a financial advisor at A.G. Edwards, he had access to real-time stock quotes provided by the firm. When he left in 2007 to start his own practice with LPL Financial, he had to buy the service, considered at the time a premium offering. It would cost him $300 a month.

“Now that I’m a business owner, am I going to shell out $3,600 [a year] just so I can look cool?” he asks. “I’m not an active trader, so it wasn’t like I needed it.”

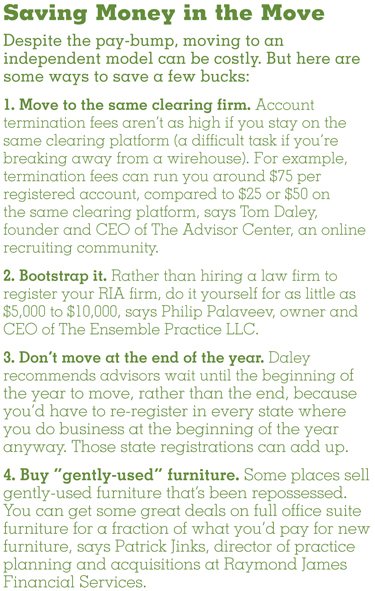

Turns out, $3,600 a year is just the beginning. When an advisor moves from an employee model to independence, the costs of doing business take center stage. The out-of-pocket expense can range from $50,000 to $130,000, depending on the number of people and custodians used, the budget for technology, how expensive the furniture is, and whether an FA sets up a registered investment advisory firm, says Philip Palaveev, owner and CEO of The Ensemble Practice LLC.

But what an advisor can’t always budget for are the opportunity costs—the revenue lost during the transition—as well as the lost assets from the clients that don’t follow, Palaveev says. Those can often dwarf the start up costs. An advisor generating $4 million in revenue, for example, can expect to lose about $1 million in revenue in the process, he says.

“When you’re changing firms, for a period of three to six months you’re going to be severely distracted by the transition, and as a result of that, you’re going to be less productive,” he says.

Broken Books

Not only does an advisor’s output decline during a transition, it’s also difficult to estimate what percentage of a book of business will follow an advisor to a new firm.

“You can budget for your expenditures; you can budget for what you’re going to spend,” says Patrick Jinks, director of practice planning and acquisitions at Raymond James Financial Services. “But what’s the most difficult thing I think to budget for is going to be the clients that you retain in that transition.”

Jinks tells advisors to be conservative in estimating what their top-line revenue is going to be.

“Let’s assume you’re a $1 million producing advisor; don’t assume that you’re going to be a $1 million producing advisor right out the gate,” Jinks says. “Assume that there’s going to be some non-retention.”

More realistically, an advisor this size could assume about 80 percent client retention, but they won’t be at $800,000 in revenue right away, Jinks says.

Some clients may follow immediately and others may take a long time, Palaveev says. If a client takes eight months to come over, for example, that advisor loses eight months’ worth of revenue from that client.

Even before sitting down with a new RIA to talk about their compliance, Chris Winn, founder and managing principal of AdvisorAssist, will ask about their client retention. In the early stages of the transition, it’s incumbent upon the advisor to get on the phone.

“I don’t want to hear how your profitability’s down when you haven’t called half your clients yet,” Winn says.

Good advisors will typically bring over 65 to 80 percent of their targeted clients within the first 90 days, says Tom Daley, founder and CEO of The Advisor Center, an online recruiting community. The remaining business tends to move over within the next 90 days.

“Oftentimes the client doesn’t understand the implications of having to return that paperwork back in immediately,” he  says.

says.

Advisors should prioritize the move based on the clients they have good relationships with, Daley says. But advisors should also prioritize those accounts that provide the most recurring revenue to add stability to their life when they first move over.

“What [advisors are] thinking about is, ‘I’m going after my largest account,’” Daley says. “Your largest account might be a $10 million brokerage account, where the guy has so much cost basis in stocks he’s held for 50 years. There’s no revenue coming off of that account.”

Broker/dealers are doing a better job helping advisors move their books of business and retain more of the assets, Daley says. (See REP.’s story in the September 2013 issue, titled “The Secret Weapon.”) In addition, ten years ago, the wirehouse firms had selling agreements with asset managers that the independent b/ds didn’t have access to. That game has changed.

“I remember 10 years ago trying to move a guy out of one of the wirehouses and a huge cost of going independent was the fact that they’d have to really figure out how to reposition assets,” Daley says.

Hidden Costs

Beyond lost time and assets, other hidden costs will creep up that advisors may underestimate.

Take client complaints, for example. If an advisor was previously with a wirehouse, complaints would be sent to the firm’s lawyers. On the independent side, the advisor is responsible for hiring their own attorney, says Winn.

Customer relationship management software is a great tool, but advisors often underestimate the time and effort it takes to build and configure this system, he adds.

“They’re now running a business that has hidden and embedded costs and they need to be able to prepare for it,” he says.

Advisors also have to take tax expenses into account when going independent, says RJFS's Jinks. Previously, their taxes were withheld by the employer.

“Now that you’re a sole proprietor, you not only have federal income tax, you could also have state income tax,” Jinks says. “You could have employment tax; you also have the self-employment taxes.”

The Paycheck

Despite the costs, many advisors who start their own practice will get a pay-bump. Some throw out figures like a 90 to 95 percent payout, but by the time you pay the broker/dealer and cover ongoing overhead expenses, an IBD advisor can more realistically expect to take home about 60 to 67 percent, Daley says.

Within the first 60 days of going independent, Rose says he brought over a large chunk of his clients and received his first check, which blew him away.

“For me, the biggest takeaway was not having to give up 60 percent to the broker/dealer,” Rose says. “That was the part when I got a check and it was the most I’ve ever made.” And, he says, he still hadn’t brought over half his book.

That’s one of the appeals of independence. But without taking into account the hidden costs of running a business, it’s largely an illusion that one channel is more profitable than another, says Palaveev.

“By and large, there’s no such thing as a magical business model that’s suddenly going to make you a lot of money because you switched over there,” Palaveev says. “It’s much like a highway—all the lanes are equal. If it’s congested, it’s congested. If it’s fast, it’s fast.”