You’ve no doubt heard the adage “All good things must come to an end.” But Geoffrey Chaucer’s original words were actually more encompassing. He thought all things must come to an end. The good and the bad.

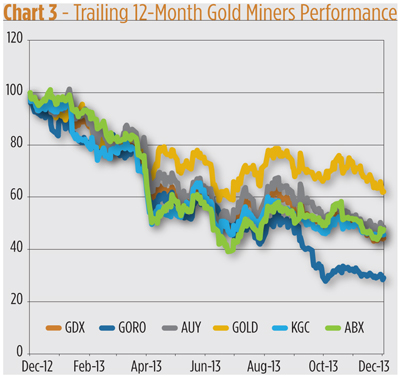

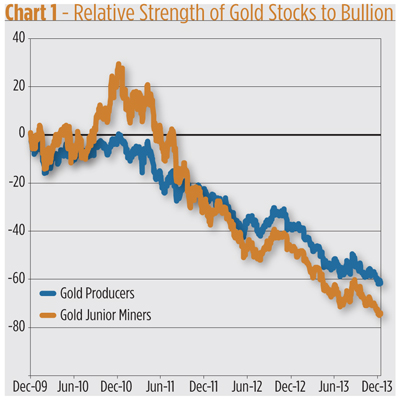

This should comfort fans of gold mining stocks. Heaven knows they could use some consolation. The market value of global gold producers sunk at twice the rate of bullion’s decline, 54 percent vs. 27 percent in the past 12 months. Things have to get better. Sometime.

That time may be now, according to Paula Bujia, Gold and Precious Metals Fund Manager for London-based Schroders plc. But, she cautions, her thesis depends on whether investors have warmed to bullion itself.

“We think that the main catalyst is investor confidence that the gold price has bottomed,” says Bujia. “With a stable gold price, we think gold producers can outperform.”

Can bullion find a foothold after slipping so dramatically in 2013?

Even some of gold’s most vehement detractors concede it is possible. “Gold and the gold miners could definitely bounce here after such horrid performance,” declares Chart Prophet LLC Executive Director and Chief Investment Officer Yoni Jacobs. “Gold could find support at $1,200 or $1,000.” (See more of Jacobs’ outlook for gold in the August 2013 issue of REP.)

Bujia’s more upbeat. While Schroders doesn’t publish an official gold forecast, Bujia looks for an average bullion price between $1,400 and $1,600 in 2014, implying as much as a 14 percent hike compared to last year.

Industry insiders seem to be favorably disposed toward the metal as well. In early December gold producer and user commitments on the Comex gold market turned net long (combined futures and options) for the first time since disaggregated reporting began in 2006.

“A net long position doesn’t necessarily create a trend,” says Jacobs, “but it could be another confirming indicator that gold is finding support at these levels.”

The case for gold stocks

According to Bujia, gold producers have slashed costs and boosted their free cash flow recently. “When the gold price starts to go up again,“ she predicts, “they will benefit enormously through margin expansion and higher dividends.”

But not all companies will rise. More marginal mining companies are being washed out. “The 11-year gold bull market allowed the creation of companies with poor assets to get financing,” she says. “This is no longer the case. The good projects will be developed by stronger hands and the poor ones will die.”

“It simply is not possible for a busted industry to keep all of the involved companies alive,” says Jacobs. “There is more bad news to come for the miners, leading to a few bankruptcies and increased consolidation in the sector.”

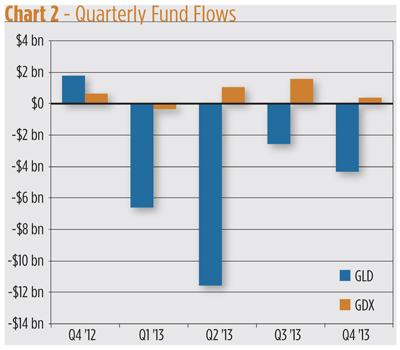

Investors, for their part, seem sanguine. The nosedive in miners’ prices has actually drawn in buyers. Over the past year, the Market Vectors Gold Miners Index Fund (NYSE Arca: GDX), an exchange-traded portfolio tracking three dozen global producers, doubled its asset base with $3 billion in fresh inflows while the bullion proxy SPDR Gold Shares Trust (NYSE Arca: GLD) bled $25 billion – half its heft.

Demand for some sort of gold exposure seems to be holding up despite sagging bullion prices. And that, says Bujia, makes a case for value hunting among the miners. She, in fact, has a short list of companies that could outdo gold this year. Miners getting the nod include Randgold Resources Ltd. (Nasdaq: GOLD) and Yamana Gold, Inc. (NYSE: AUY), both low-cost producers in her estimation. In the “very cheap” category, Bujia likes Kinross Gold Corp. (NYSE: KGC) and Barrick Gold Corp. (NYSE: ABX).

Yamana is Canadian-based with sizeable production, development and exploration properties in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Mexico and Colombia. Randgold is engaged in the exploration and development of gold deposits in Sub-Saharan Africa while Barrick manages production from its North American, South American, Australian and African operations out of its Toronto headquarters. Kinross, also based in Toronto, has operations in North and South America, the Russian Federation, and Africa.

Jacobs isn’t as enamored of these miners. “Even after huge drops in their stock prices, their price-to-earnings ratios are still high,” he says. “Yamana’s trailing P/E multiple is 21.2. It’s forward P/E is 17. After such a devastating drop and taking into account that future earnings won’t be as powerful as they have been in the past, the P/E should be much lower to be attractive. Rangold’s trailing P/E is 18.7 and its price-to-sales ratio is 4.5. True value plays are closer to 1.”

For Jacobs, debt is especially worrisome. “Yamana has $1.1 billion in debt but only $232 million in cash. Barrick has an outrageous $15.4 billion in debt -- almost equal to its entire market capitalization -- but only $2.3 billion in cash,” he grumbles.

To boot, these miners can ill-afford their dividend payouts. “Kinross, “ says Jacobs, “had negative earnings and twice as much debt as cash, yet still intends to pay a 3.4 percent dividend. Is that sustainable?” Dividends are financed by free cash flow, or the cash a company generates after paying for the maintenance of its asset base. Free cash flow also pays for new acquisitions and debt reduction.

If Bujia’s free-cash-flow benchmark flags any recovering miner, Gold Resource Corp. (NYSE MKT: GORO) ought to be on any value hunter’s target list. The Colorado-based company engages in gold exploration and production in Mexico. Its stock was positively drubbed over the last 12 months – losing nearly three-quarters of its market value – and now offers an enticing 19.4 percent free-cash-flow yield.

Dividing a company’s free cash flow per share by its current stock price derives a free-cash-flow yield. Savvy investors often look at free-cash-flow yield as a better return metric than an earnings yield. None of the stocks in Bujia’s short list have chalked up positive free-cash-flow yields recently; that seems to confirm Jacobs’ rather dismal diagnosis.

About the miners’ misery, Jacobs adds: “We have to remember why all of this devastation has happened and how it can get worse. The miners simply stopped hedging as gold prices soared to all-time highs, taking enormous risk at the worst possible time. The miners are stuck in terrible financial situations with very little room for growth.”

Competition fostered by the bull market for gold prices pushed up the costs of mining, putting further pressure on producers’ earnings.

“We have already seen earnings decreases, unhappy shareholders, rising mining costs, worker strikes, and leadership turnover due to falling gold prices and poor performance,” says Jacobs. “I don’t think the weak hands have truly been washed out. Perhaps the cost reductions and abandonment of unprofitable projects will help some of these mining companies recover a bit, but their situation could still deteriorate significantly if gold prices fall further. Some will recover and see a new day, but there will be a number of bankruptcies “

The risk of going kaput

So how do investors seeking gold exposure gauge the bankruptcy risk of a gold producer? Luckily, there’s a metric that does just that. Years ago, New York University professor Edward Altman developed the Z-score formula to test a company’s financial strength. An Altman Z-score is derived as a weighted sum of factors including a company’s earnings, assets and equity market value and other financial measures. A score below 1.8 indicates a high likelihood of a date in bankruptcy court while companies earning scores above 3.0 aren’t likely headed for a Chapter 11 scenario.

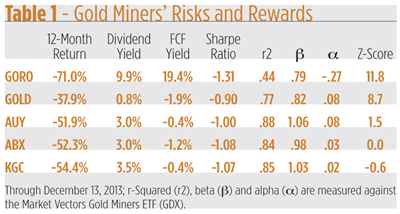

Table 1 lays out the trailing 12-month performance of the five gold miners discussed above, along with each company’s current Z-score. While all these issues are much cheaper in dollar terms than they were a year ago, only one – Gold Resources – represents a true bargain, owing to its positive free-cash-flow yield. Most important, though, is the company’s Z-score. At 11.8, it bespeaks financial strength or, more properly, a lack of financial weakness. Value investors may be more likely to realize their bargain with an investment in Gold Resources rather than the other stocks.

Randgold, it should be said, also rises above the bankruptcy risk threshold with an 8.7 Z-score, but is still under water on free cash flow. Caveat emptor.

The rest – Yamana, Barrick and Kinross – could, by virtue of their low Z-scores, be candidates for some sort of reorganization or consolidation. For these stocks, perhaps fugiat emptor* is a more proper warning.

*“Buyer stay away”