In February, the White House published its annual report on the economy, within which the Council of Economic Advisors included a fairly lengthy discussion around the growing use and impact of robotics and automation. While the research highlighted the likelihood for a paradigm shift as it relates to employment in the U.S., what may have been overlooked was the effect on clients and consumers at large. For those in the custody market, who are witnessing the tech revolution occur in real time, it is already clear that the growing reliance on automation has altered the customer experience significantly in just a few short years.

To be sure, technology adoption has introduced several benefits for custody providers. From a client perspective, the efficiencies that have come alongside the advances in technology have generally resulted in lower costs. Moreover, when it comes to the services a traditional custody bank provides, technology has also facilitated more effective ways to communicate rote business needs, whether it's to obtain trade information or initiate simple actions, such as wire requests.

What most private wealth clients may not realize, however, is that among the larger custody banks and brokerages, much of the tech spend is focused on either servicing institutional relationships, such as asset owners and fund managers, or moving into new, adjacent businesses that leverage the massive amount of data at their disposal to sell information-driven services back to the same institutional clients. The push toward automation, meanwhile, is often leaving private wealth advisors and smaller family offices on the outside looking in. And as independent RIAs look to compete against the growing army of algorithm-fueled robo advisors, an automated and impersonal custody offering actually cuts against the value proposition they aim to offer to their clients.

The Evolving Custody Landscape

The custody industry has experienced a massive wave of consolidation during the last 10 years. This has been driven by a number of factors, ranging from historically low interest rates, which have reduced the spread custody providers earn, to the unrest created by the 2008 financial crisis, which saw several banks sell off their custody operations to meet capital requirements. A mountain of new global regulations has tilted the playing field further to those custodians that enjoy the greatest economies of scale, providing yet more impetus for the largest players to become even larger.

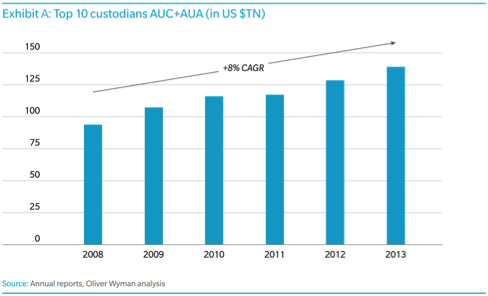

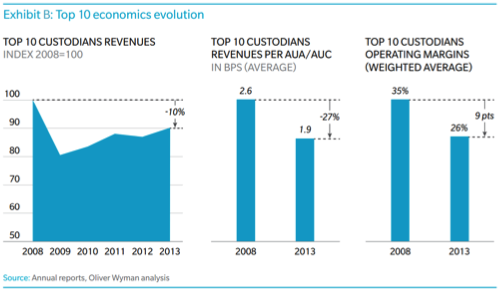

A study from management consulting firm Oliver Wyman published last year, highlighted that among the top 10 custodians, assets under custody and administration (AUC/AUA) expanded at a roughly 8 percent compound annual growth rate between 2008 and 2013 (see Exhibit A). This growth, driven largely by M&A, overshadowed a parallel decline in both revenues and operating margins. Sales per AUC/AUA were down 27 percent from 2008 to 2013, according to the study, while operating margins shrank from 35 percent to 26 percent over the same period among the top 10 providers (see Exhibit B).

This consolidation has effectively led to a bifurcation in the custody market, in which the dominant players are split between the traditional, fee-based custodian banks and the large brokerage platforms. In contrast, many of the mid-sized banks that historically offered custody have exited the business altogether, leaving a noticeable vacancy in the market in which the boutique providers, who can offer hands-on, high-touch services, are increasingly difficult to find.

Among the largest custodian banks and brokerage platforms, the adoption of technology, beyond complementing their service offerings, are increasingly defining them. This march toward automation represents the next stage of the custody market's evolution. Indeed, many of the largest providers are effectively repositioning themselves as tech and information companies, which as Oliver Wyman points out, generally attract higher Price/Earnings ratios.

The latest annual reports from the largest players document both the progress and end-state visions as they re-imagine themselves as digital enterprises offering big data capabilities. BNY Mellon, last year, launched NEXEN, a digital technology ecosystem that generates predictive data and insights. This technology, they claim, will be able to anticipate client needs. JPMorgan boasted about its more than $9 billion technology spend and how its investments in big data are leading to efficiencies in its custody business. And State Street introduced State Street Beacon, the next stage of the company's Business Operations and Informational Technology Transformation program. In outlining its Beacon roadmap during its most recent Investor Day, State Street highlighted that by 2020, the bank expects to cut as many as 7,000 jobs worldwide thanks in large part to automation, and also identified a savings goal of $550 million over the next five years.

The Impact on Wealth Managers

Welcome to the age of digital custody. Wall Street is applauding the effort due to the focus on expenses, but in putting technology and automation at the heart of their service offerings, this new era will likely prove to be a boon for some, but a burden for the majority of clients, particularly those focused on private wealth. Automation is meeting institutional clients' demand for international investment services, straight-through processing, platform integration, workflow solutions and big data insights. But, as these capabilities eventually become part of the woodwork, they will likely fail to provide any enduring competitive advantage.

It's hardly surprising that the global custodians are prioritizing bigger, more lucrative projects, like back-office infrastructure to settle trades, or initiatives that will reduce their own costs. In a way, the big custodians are becoming victims of their own success. The bigger they become - and the more dependent they are on technology - the less ability they have to handle anything that deviates from the system. In this tech-heavy workflow environment, manual intervention becomes nearly impossible unless it's a contingency measure in the event that clients are experiencing business interruptions. And let's not forget that one of the biggest stories in the custody market last year involved a software glitch, the result of a corrupted accounting systems upgrade, that led to inaccurate NAVs for thousands of mutual funds and ETFs.

The same catalysts that are driving the bigger players to pursue consolidation - the shrinking margins and higher costs of compliance - are also affecting smaller custody providers. Without the option of scaling up, however, many smaller providers are scaling back, which means fewer resources for clients. We've also witnessed a growing trend in which the small regional banks that still offer custody actually outsource the back-office and administration to the one of the Big Four custodians, which creates just another layer to be navigated for clients.

But for private wealth clients, the biggest issue still boils down to whether or not they can receive hands-on, high-touch service, and given where these clients fall on the priority scale of the largest banks, there seems to be waning appetite to meet the high demands of this audience. At State Street, for instance, private wealth assets represent less than a single percentage point of the $27 trillion of assets currently held by the bank. Many of the smaller custodians, meanwhile, simply don't have the labor power to meet these demands either.

For clients with assets of between $50 million and $1 billion under management, which is no small sum, it can be particularly frustrating to go from working with dedicated relationship managers, who know their business, to adopting a "1-800 service" model, featuring a new representative with every new request. But even advisors with $2 billion of AUM would likely fall well outside of what the largest custody banks would consider to be their top-tier clients, those asset owners and fund managers whose AUM is measured in the hundreds of billions.

So what does this new service model look like from the perspective of a private wealth manager? In most cases, the technology will be forced on them. If a client wants to make a wire request, it has to go through a system, one that was more likely designed with institutional back-office administrators in mind, who may also have IT resources available to facilitate any technological needs. If the request wasn't initiated correctly, it gets rejected. If there are other issues, it may linger in queue before those are discovered and clients are asked to resubmit their request from scratch. Representatives, who very likely are having their first interaction with a given client, are typically unable to intervene, and the very idea of a manually facilitated wire transfer no longer exists in a workflow-driven environment.

Keep in mind, this is a request that should take 10 to 15 minutes when it's completed manually, but can extend past 48 hours once it's introduced into the digital bureaucracy and becomes just another transaction in queue. As most advisors well know, this delay, when the request is urgent, can strain even the closest client relationships.

What's a Wealth Manager to Do?

Most advisors realize the momentum is moving away from delivering the hands-on services required for private wealth managers. Whereas in past eras the decision-making process was fairly easy to choose a custodian, with the rapid evolution of the market, due diligence can be far more involved today. For instance, private wealth advisors will want to ensure that there is a commitment to the underlying technology, but not at the expense of personalized service. Moreover, advisors should have a sense of a custodian's financial wherewithal and performance trends. On the large end, if margins have been shrinking, the focus will be on finding efficiencies and cost cutting; for smaller custodians, the performance could speak to the viability of the business. Also, beyond understanding the service model, advisors will want to understand how much experience their representatives have and their tenures at the companies in question. Employee turnover can be just as frustrating as an offshore call-center experience, and will preclude any kind of long-term relationships from taking root.

Of course, all this is not to say that all technology should be viewed in a negative light. Custody-centric platforms that automate trading, account reviews, compliance processing and performance reporting are critical functions and would be considered the ante for doing business today. But most private wealth managers still have far too much at stake to place all of their trust in an automated network, that while it's billed as innovation, is premised on expense reduction first, and an enhanced experience second - priorities that are more often in conflict than aligned.

Scott Sumner is a vice president and head of custody at Fiduciary Trust Company, which specializes in investment management, estate and financial planning, trust and custody services for high-net-worth families, charitable organizations, family offices and advisors.