The nation's health reform debate has been raging for three years, but one of the most critical questions seems to have fallen by the wayside: The risk that a major long-term care need will devastate the savings of seniors.

The current system for financing long-term care is fragmented. The stressed Medicaid system is the nation's largest insurer. Medicare provides limited coverage, and the commercial long-term care insurance business remains a struggling niche product for mass affluent buyers.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) aimed to create a new "public option" for long-term care insurance, called the The Community Living Assistance Services and Support (or CLASS Act). The intent of CLASS was to expand coverage by providing a basic, inexpensive LTC option deployed mainly through the workplace.

CLASS was shelved by the Obama Administration late last year after actuaries concluded that the plan wasn't workable. But that doesn't mean the need we don't need new approaches to long-term care.

Experts estimate that 70 percent of Americans over age 65 will need some type of long-term care. Of course, not everyone will require nursing home care – many seniors will receive care in community settings or from family members at home.

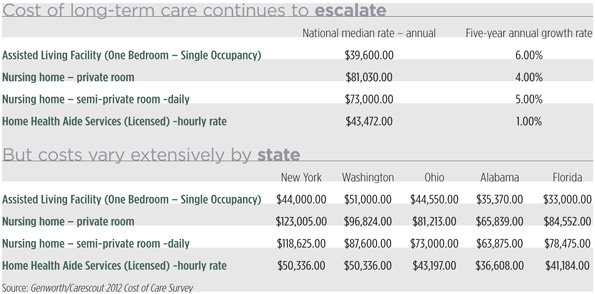

But those who do need nursing home care will be facing expenses that can be devastating. The median annual cost of a private nursing home room this year is $81,030, according to the 2012 Genworth/Carescout Cost of Care survey. That's $15,330 more than in 2007, and a 4 percent five-year growth rate. The cost of in-home and community care is rising at a more moderate pace – and the cost of care varies tremendously around the country (see chart).

Self-insuring is an option, but could require allocating a substantial portion of household assets to pay for long term care, when that money could be earning a return and funding retirement for a spouse or heirs. Some families also rely on tapping home equity via a home equity loan or reverse mortgage.

Medicare will cover up to 100 days of skilled nursing care or rehabilitation if it is ordered by a physician. Patients must have already been enrolled in Medicare Part A (hospitalization), and have been formally admitted to a hospital for at least three consecutive days. After 20 days, patients are responsible for a small co-payment.

Medicaid covers nursing home and community-based care – but only if you are indigent or receive Social Security disability payments. Some patients begin by paying for care out of pocket and go on Medicaid later after their resources have been exhausted.

Medicaid is funded jointly by the federal government and the states, and administered at the state level. Income eligibility vary by state, but the program generally is aimed at very low-income patients. An individual can’t have more than $2,000 in “countable” assets – $3,000 for a couple – which includes everything but personal possessions, one vehicle and the patient's principal residence.

Medicaid also provides a safety net for people who become “medically needy” due to high LTC expenses. In these situations, the applicant needs to have spent down assets to a state-defined eligibility standard. But Medicaid also reviews the five years prior to the application to prevent abuse of the program through asset transfers.

Medicaid funding also faces an uncertain future due to ongoing budget battles in Washington and stretched state budgets. Many states are trying to cut their LTC costs by applying for federal waivers that allow them to shift to managed care programs. And those changes could accelerate if Republicans succeed in their efforts to transform Medicaid into a block grant program to states.

That leaves older Americans – and their financial planners – with a hodge-podge of problematic options—and few new solutions on the horizon from policymakers. “There are people in the federal government thinking about this question, but there have been people thinking about this for the last 20 years,” says Richard Johnson, senior fellow and director of the program on retirement policy at the Urban Institute.

For financial planners serving mass affluent clients, the commercial long-term care insurance market (LTCI) looms large as the solution of choice–despite several years of negative news. Policyholders have been hit with waves of double-digit rate hikes, and the price of new policies has soared. Meanwhile, a long list of major insurance companies have stopped writing new individual policies, including Prudential, Metlife and Allianz.

“We're still supportive of long-term care insurance,” says Michael Kitces, partner and director of research for Maryland-based Pinnacle Advisory Group. “With prices ratcheting up, it's not doable for a larger number of our clients. But it's still affordable for a wide base of moderately-affluent clients.”

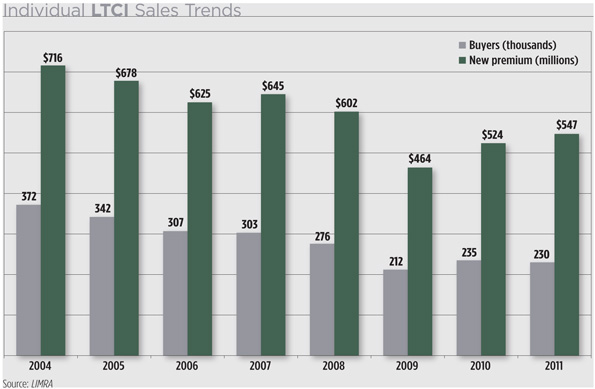

LTCI is limping along as a niche business. Overall penetration remains less than five percent of the total possible market, according to LIMRA, the insurance industry research and consulting firm. Sales of individual policies fell sharply during the 2008-2009 recession, and have recovered only modestly since then. LIMRA reports that in 2011, just under 230,000 Americans purchased individual policies – down two percent compared with 2010, and 24 percent lower than the sales pace in 2007.

“I don't think the number of buyers will rise much in this economy,” says Jesse Slome, executive director of the American Association of Long-Term Care Insurance (AALTCI). “It's not a universal solution – it's a niche solution.”

The cost of LTCI in a weak economy is a key driver of the sales downturn.

Long-term care insurance policies cost anywhere from 6 to 17 percent more this year than in 2011, according to an annual survey by AALTCI, which adds that rates are 30 to 50 percent higher than five years ago. A 55-year-old couple purchasing long-term care insurance protection can expect to pay $2,700-per-year (combined) for about $340,000 of current benefits.

And existing customers have been roiled by very large rate hikes, which has undermined consumer confidence in the product. Genworth, for example, said in July that it would ask state insurance regulators around the country for rate hikes around 50 percent on many in-force policies – mostly older policies with unlimited lifetime benefits and high annual inflation adjustments.

The ultra-low interest rate environment is a key factor driving the rate hikes and new policy pricing. Insurance companies haven't been able to earn enough on their fixed income portfolios to fund benefits. Forty to 60 percent of the dollars an insurer accumulates to pay future claims comes from investment returns, according to AALTCI.

Another challenge for insurance companies, oddly enough, is customer loyalty. Once purchased, it makes sense to hold on to an LTCI policy. You may not be able to find new coverage due to medical underwriting issues, and prices will have risen in the intervening years. What's more, insurance companies benefit when policyholders walk, because they've collected premiums and carry no risk of paying out future benefits.

And policyholders have been holding on tight. Lapse rates for individual LTCI remain low with just three percent of policies unaccounted for at year-end, according to LIMRA – a rate that is much lower than for other types of insurance – and much lower than the industry had expected.

Alongside higher prices, insurance companies have also been moving to make LTCI more profitable through changes in policy designs and tighter underwriting standards. If you're assisting clients looking for policies, here are the key market trends to watch:

Pricing. The industry is at the tail end of those large rate hikes, argues Kitces. “This coverage is never supposed to be re-priced,” he says. “It only happened because no one a decade ago predicted lapse rates as incredibly low as they've been, or that interest rates would plunge as far as they did. But all that is in the pricing now. That means a policy issued today has the lowest risk of any policy issued in the history of the business. The risk of moving further in the wrong direction is very low.”

Some financial advisers have been advising clients to hedge against the risk of premium hikes by telling clients to purchase less coverage in order to make sure policies remain affordable even if rates jump. Kitces thinks that's the wrong approach. “Most planners I talk with are obsessed about building in all this padding, but the storm has already passed.”

Notably, the AALTCI survey found that pricing varies widely among carriers, which means it pays to shop around. “For the 55-year-old single policy applicant the highest price policy cost almost 80 percent more than the lowest priced policy,” says Slome. “For some categories, the difference was as much as 132 percent and no single company always had the lowest nor the highest rate which is why we stress the importance of comparison shopping.”

Less generous policies. Insurers have been capping lifetime benefits, and reducing inflation riders to three percent (compounded). “Three percent inflation protection is the new five percent,” Slome says.

Most new policies will cover three years of care, which will be sufficient for all but 20 percent of policyholders, according to Milliman, the actuarial consulting firm; just 15 percent will need more than four years of benefits and only 10 percent will require more than five years of care.

Genworth, which is a market leader in LTCI, recently reduced spousal discounts for couples purchasing policies together, and discounts based on good health. Policies covering couples have been an especially good deal for women, who tend to outlive men. But Genworth will introduce gender-based pricing next year, a move that will set an industry trend, according to Dawn Helwig,a principalat Milliman who follows the LTCI business closely. “For the first-time, we're going to see gender-based rates,” she says.

Genworth also eliminated unlimited lifetime benefits on new policies. “Within a few months of that announcement, most all the other major carriers followed suit,” Kitces says. “The insurers are moving more in lock-step, because no one wants to be the only one writing a more risky benefit than everyone else.”

Tougher underwriting. Many insurers have tightened up medical underwriting in order to more accurately assess risk and manage profitability. That means it may be tougher for clients to buy a policy if they wait too long. Most experts advise buying LTC insurance no later than the late fifties, when pre-existing conditions are less likely to be a hurdle.

Disappearing payment options. Major carriers have moved to eliminate “limited pay” options on new policies, which allowed customers to fully pay for a policy over 10 years or in a single premium. “That was popular for a while, because once you finish paying the insurance company has no way to raise your rates,” Kitces says.”

Employer-based sales shrinking. Purchasing LTC through an employer has been another option, but that market is shrinking. Over the past two years, insurers suspending or exiting the group market include John Hancock, Met life, Unum and Prudential. Last year, just under 84,000 new participants signed up for LTCI via group plans, according to LIMRA – 17 percent less than in 2010.

Mark Miller is a journalist and author who writes about trends in retirement and aging. He is a columnist for Reuters and also contributes to Morningstar and the AARP Magazine. Mark is the author of The Hard Times Guide to Retirement Security: Practical Strategies for Money, Work and Living (John Wiley & Sons, 2010). He edits RetirementRevised.com. Twitter: @retirerevised