FINRA has stepped up the number of cases and the value of fines they levied against advisors last year, but that doesn’t neccessarily mean that the indstury's self-regulatory organization is getting any tougher.

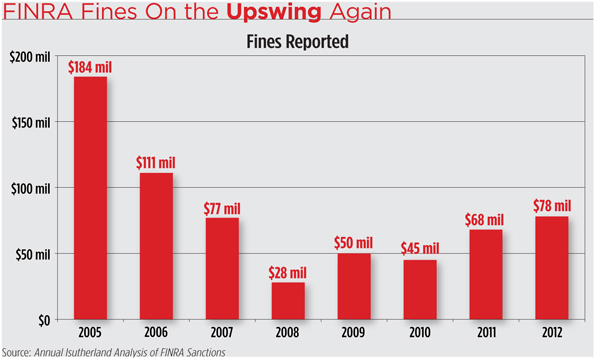

FINRA increased the size of its fines by nearly 15 percent in 2012, and also upped the number of disciplinary actions it opened, according to a new study released by Atlanta-based law firm Sutherland Asbill & Brennan.

“In the wake of the financial crisis and some of the problems it revealed, we are seeing greater enforcement by regulators,” says Skip Schweiss, Managing Director of Advisor Advocacy and Industry Affairs, TD Ameritrade Institutional.

According to Southerland, the number of cases brought by FINRA has increased 44 percent since 2008, to 1,541 in 2012.

But that doesn't neccessarily mean the agency is getting tough on enforcement, say critics. Only a small fraction of the 629, 980 registered securities representatives that FINRA oversees—not to mention the almost 4,300 brokerage firms under the regulator’s supervision—were served with enforcement actions.

Meanwhile, the $78.2 million in fines levied by FINRA in 2012 is substantially dwarfed by the more than $3 billion in penalties and disgorgement gained by the SEC during the 2012 fiscal year.

Further the $34 million that FINRA ordered firms and representatives to pay in restitution only represented 1.3 percent of the $2.63 billion in assets under management controlled by broker dealers as of December 2012, according to SIFMA.

“Given the number of representatives and firms it supervises, I'm surprised the total amount of fines is so anemically small,” says Ron Rhoades, president of ScholarFi and former chair of NAPFA

While FINRA makes referrals to the SEC of larger cases—which may account for some of the federal agency’s penalties—Rhoades says the fines levied by FINRA remain just a "cost of doing business" by FINRA’s broker-dealer firms.

FINRA's fines also continue to support its budget. While in concept they are segregated off to provide for capital improvement items, there is no doubt that the fines levied by FINRA end up indirectly supporting the very same broker-dealer firms upon whom the fines are levied, Rhoades says.

Instead, if such fines were paid to the U.S. Treasury, rather than to FINRA, then the agency would have to raise its regulatory fees. “It seems an unwarranted conflict of interest that a regulator can impose fines to support the infrastructure of the regulator with regard to inspections and examinations,” Rhoades says.

Because of ongoing budget problems that FINRA possesses, examiners and enforcement officers may be motivated, even unconsciously, to levy more or higher fines in order to preserve their own positions from budget cuts, Rhoades says.

David Tittsworth, executive director of the Investment Adviser Association also cautioned against drawing too many inferences about what these increases mean beyond the basic premise that both the SEC and FINRA appear to be trending toward more cases and higher fines.

“Strictly from a numbers standpoint, it is clear that FINRA has brought more enforcement cases but that its fines are dramatically less than the SEC,” he says. “I think we’ll need more information over time to assess whether shifts in annual numbers translate to a significant enforcement trend.”