Over the past few years, the popularity of TED (Technology, Entertainment and Design) Talks has mushroomed. The talks, in case you haven’t seen any, are a series of concise “big idea” presentations made by scientists, artists, educators and others to a global audience via free media.

The first TED conference was held in 1984, but that wasn’t the debut of the “TED Talk.” That actually started in 1981 when Eurodollar futures were launched by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). Eurodollars, the “ED” in the financial “TED” acronym, are time deposits of U.S. currency held in foreign banks. The “T” originally represented another CME contract, Treasury bill futures, which debuted in 1977.

Originally, the talk about “TED” referred to the TED spread—the implied yield difference between “risk-free” three-month T-bills and three-month EDs represented by the London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor).

T-bill futures were discontinued in the wake of the 1987 market crash, but the TED spread survived as the variance between cash Libor and Treasury rates (Libor minus Treasury).

Market observers, bankers and traders track the TED spread as a credit risk indicator and as a metric of liquidity. A rising spread (Libor rates rising above T-bill yields) typically signals a perceived increase in counterparty risk. Spikes in the spread often presage sharp declines in the U.S. equity market. A declining spread, on the other hand, heralds decreased loan default risk or, in the extreme, an increased risk of a U.S. government default.

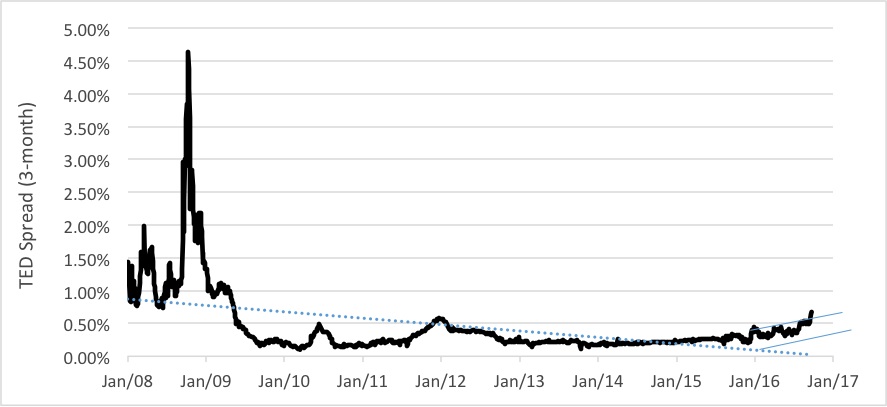

Historically, the spread trades between 10 and 50 basis points (0.10 and 0.50 percent). Indeed, that’s been the case for the past seven years. But look at the chart below and you’ll notice a couple of things. First, there’s the spread’s spike to 464 bps at the height (depth?) of the 2008 financial crisis—a time when widespread defaults were feared. Now look to the opposite side of the chart and you’ll see another widening of the spread—less dramatic, to be sure, but still a breakout above the 50 bps level.

The TED spread closed out last week at 67 bps and seems to be headed higher yet. Is this an early warning of troubles to come? Well, there has been a baseline increase in the cost of unsecured U.S. dollar funding over the past two years. But what about the more recent acceleration?

It’s likely that the credit markets are simply adjusting to new regulations set to go into effect on October 14, which has led to a contraction in available dollar-based funding. Demand for prime money market funds, portfolios primarily made up of corporate debt such as commercial paper and certificates of deposit, is waning ahead of the imposition of rules shortening their weighted average maturity from 90 to 60 days. Additionally, institutional money market funds will be compelled to adopt a floating NAV (net asset value) and be allowed to establish “gates” to slow redemptions in a financial crisis. Government money market funds aren’t subject to these regulations.

Not surprisingly, assets have been moving from prime funds to government funds, increasing borrowing costs for issuers of commercial debt. As money available for prime paper dries up, Libor rates have ticked up.

So, what we’re seeing isn’t a brewing crisis, though the TED spread should still be carefully monitored. Still, there could be continuing fallout from a stronger dollar and, consequentially, weakness in the commodity sector.

Brad Zigler is WealthManagement.com's Alternative Investments Editor. Previously, he was the head of Marketing, Research and Education for the Pacific Exchange's (now NYSE Arca) option market and the iShares complex of exchange traded funds.