The explosion of exchange traded funds in recent years is not news; the total fund population now approaches some 2,200 and shows little sign of slowing down.

That is arguably good news for ETF investors—or is it? After all, more choice doesn’t always lead to better decisions. In fact, too many options can often lead to paralysis. Does the proliferation of ETFs lead to more investor options, or more confusion? Is it possible to have too many ETFs?

“I’m not worried about a particular corner of the market,” says Ben Johnson, director of global ETF research for Morningstar. “My concern is that the market transitioned long ago from innovation to a period of proliferation for all types, including niche and in some cases gimmicky funds. It’s evolved to a lot of spaghetti being thrown at the wall over the past few years, and few of the strands have managed to stick.”

For instance, in recent weeks the market has seen the disappearance of a whiskey-themed ETF and a multifactor water infrastructure ETF, recently launched market “solutions” that went searching for a problem to solve.

Not everyone shares that idea. “Throwing spaghetti against the wall? I’m fine with it,” says Eric Balchunas, senior ETF analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence. “For every five duds, you get a ROBO,” referring to the Robo Global Robotics and Automation Index ETF, which launched in 2013. It has $2.1 billion in assets and a three-year annualized return of 14.3 percent as of June 28, according to Morningstar.

“People vote with their feet,” Balchunas says. “Only 1 percent of apps make it, and no one complains about that.”

Johnson says, however, that even the more successful of recent products largely fall into “sexy themes,” a kind of “hot take” on the markets and the economy, and it’s not always clear that’s the best way for individuals to invest. He mentions robotics, blockchain technology and the launch of blockchain in China as examples. “They’re all somewhat interrelated,” he says. “It’s less being launched on the basis of lasting investment merit, and more opportunists trying to gather assets based on a theme that at any time captures investors’ imagination.”

Todd Rosenbluth, director of ETF and mutual fund research at CFRA research firm, sees a particular danger zone in the explosion of so-called “smart beta” funds, or funds that apply a non-traditional weighting to an index based on various financial factors. “You have 700 or 800 smart beta ETFs essentially fighting over 20 percent of ETF flows,” Balchunas says. “They have such different strategies. Some take magnifying glasses to go through, and I don’t know who has time.”

These funds tend to be less straightforward for investors and advisors, require a lot more education and a lot of free time to rummage around in the fine print to compare and contrast options. Their expense ratios are similar, with many at less than 25 basis points, so it’s difficult to just screen by cost.

“There are so many factors used in so many ways in these funds,” Rosenbluth says. “You need to look inside the portfolio and understand the individual and collective exposure you get. The devil is in the details with these products. They can get quite complicated.” It’s a challenge for advisors to select funds simply and on their own, he says.

Meanwhile, Dave Nadig, managing director of ETF.com, a unit of Cboe Global Markets, has a completely different take from Balchunas and Rosenbluth on smart beta. The most crowded area is in low-cost vanilla beta funds, where meaningful differentiation is next to impossible beyond cost, he says. “Part of the reason there is so much activity in products like smart beta is that this is where there’s more greenfield.”

When it comes to the vanilla beta ETF, “the chance that there could be a successful launch of another one is zero, unless there’s some incredible distribution and brand advantage, such as Google or Amazon,” Nadig says.

Nadig says the whole market has become confusing for advisors and investors as a result of its massive growth, and for that, he offers a simple remedy: “I would stick to a traditional beta fund—a boring fund in Morningstar-style boxes.”

“The market will only get more complicated,” Nadig says. “So due diligence will only get harder. Continuing education is a requirement.”

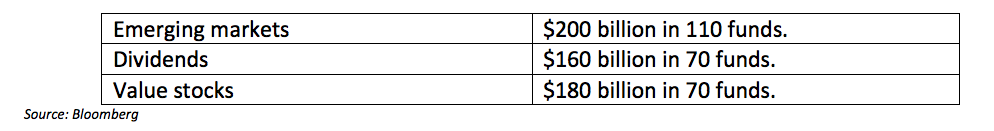

Balchunas sees possible overcrowding in some other sectors too. Environmental, social, governance funds is one. There’s already some 60 ESG funds competing for only $5 billion in assets. “Compare that to robotics, which has almost $10 billion in just three funds,” Balchunas says.

In addition, there are technology ETFs, with $160 billion in 63 funds. “It’s sort of like there’s so much to choose from, you can’t even order,” Balchunas says.

The key question is how much potential any particular area has, Balchunas says. “There are 2,170 ETFs, but about 7,500 mutual funds. If you think many mutual funds investors will switch over, ETFs are right where they should be.”

As for why there may be excess ETFs, “any number of actors are trying to jump on the bandwagon to benefit from the halo effect of the category,” Johnson says.

Then there’s the flip side to that. “The vast majority of investor money continues to flow to seasoned ETFs, the most broadly diversified, vanilla exposure at rock-bottom costs,” he says. “Most investors are still keeping it simple and cheap.”