The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco recently assessed the impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that cuts taxes by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years, the largest stimulus since the guns and butter era of Vietnam (and we know how that ended) in a release titled “Fiscal Policy in Good Times and Bad.”

Let me take you to the conclusion: They deem the tax cuts as large and front-loaded, but coming at the end of a long growth cycle, chances are their impact will be much smaller than during a contraction, and forecasts for large gains to GDP “may prove overly optimistic.”

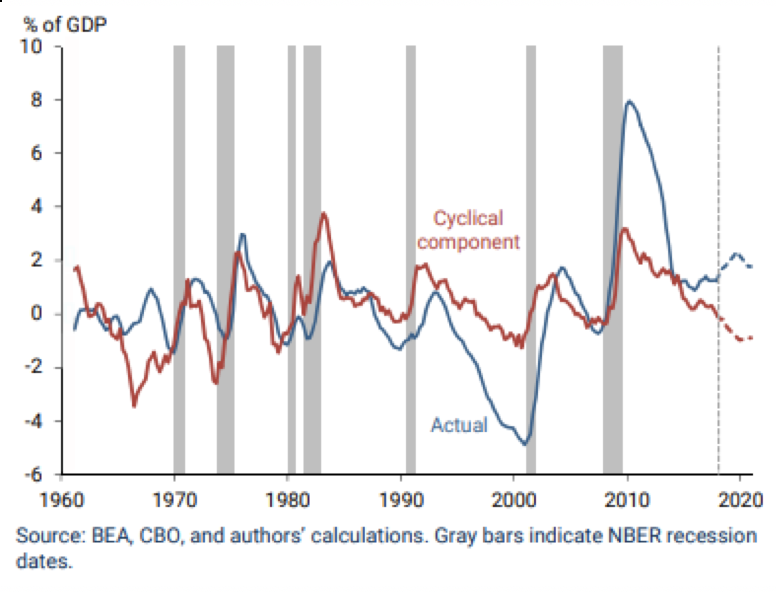

The Fed Research goes like this: Federal fiscal policy has historically been highly counter-cyclical, but you know that; revenues decrease in downturns while spending increases, and vice versa. Highly so. The chart below, lifted from their research, shows the relationship between the cyclical component of the deficit versus the actual deficit. They clearly correlate extremely well. The exception was during the Vietnam War—when we had high government spending inside of an economic expansion.

Note the dashed lines out to 2020. These lines diverge (and unusually so given the history back some 60 year), as the authors’ model projects an increase in the deficit as a percentage of GDP but a sharp decrease in the cyclical component.

Two concerns arise, they say. First, is the ability of fiscal policy to deal with future downturns; and second, is just how much stimulus we’re getting from the tax plan or in academic language, bang for your buck. Apparently, there’s been quite a bit of research on the topic though because of the rarity—fiscal stimulus in an expansion—not a lot of confident conclusions to generate. It’s somewhat more common on a state level or overseas. And even then, domestic studies find those periods of increased spending are largely military-based or focused on spending as opposed to tax cuts—specifically procyclical tax cuts.

The burden of evidence falls on the measures of the marginal propensity to consume. Since the marginal propensity to consume is higher for folks that can’t borrow or sell assets to spend their money, logic dictates there are fewer of them around at the long end of an expansion so additional dollars have a relatively lesser impact.

They didn’t say this, but I will: given that the tax cuts are weighted toward high earners and corporations, owned by high earners, there would seem to be very little implication for the MPC folk just mentioned. The authors end by saying a number of forecasters expect 2018 GDP will be as much as 1 percent higher because of the tax break; however, “[t]he literature … suggests the true boost is more likely to be well below that, as small as zero according to some studies.”