The thing I took away from pretty much all the events of the last week is further cause for curve flattening.

First, we had a more hawkish Fed and can, with a higher degree of confidence, price in more hikes in, say, the next four quarters at least.

Second, we had relatively benign Consumer Price Index after a Non-Farms Payroll report that continues to reveal tame wage pressures—Powell mention as much in his press conference as a “a bit of a puzzle.” (Real Average Hourly earnings are flat year-over-year and Weekly Earnings are up just 0.3 percent.) A sidebar to that is a tame gain in import prices (except oil), up 1.8 percent YoY in May.

Third, we had the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank taking something away from bond buying, which could be deemed at least somewhat risk-off. (As an aside, given that the ECB’s buying involves corporate bonds, I wonder if the exit from quantitative easing puts upward stress on credit spreads to the benefit of sovereigns.)

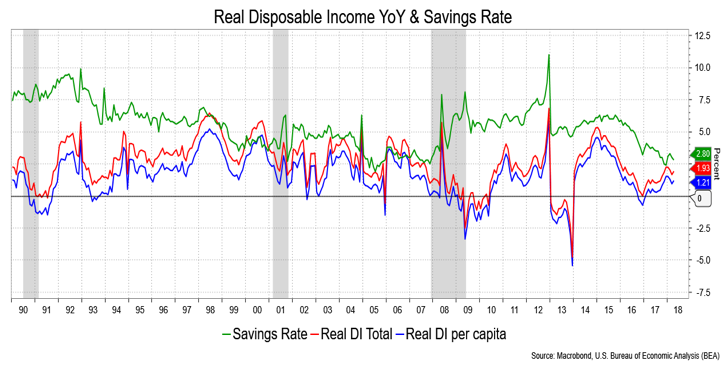

Fourth, we had strong data in the form of Retail Sales, which only enhances the Fed’s narrative. That strong Retail Sales are in part due to consumers dipping into savings—a process I don’t think can last given the already low level of savings—is beside the point. (See chart below.) The Fed knows this but is newly confident that it will get to its inflation targets: the economy is firm and that wages will soon follow. There was ample talk of the wage stimulus stemming from the tax cuts yet to be seen which is, reasonably, expected to act its part.

Fifth is the tariff story. Yes, it could prove inflationary, but it probably, for now, inhibits businesses from investing more—and they’ve been inhibited in this cycle heretofore. I’m not sure it’s contributing much to curve bets, but I put it out there as something that might warrant a risk-off edge to Treasurys.

Sixth, there is some risk that the Fed will stall the reduction in its balance sheet activity. With concern out there over a dearth of dollar liquidity due to Fed balance sheet reduction (and perhaps the repatriation of overseas dollars), there’s an argument to be made that the Fed won’t reduce it as much as has been suggested, to say, $2.5 trillion. If this sentiment gains traction, then the result would be more reinvesting down the road to hold the balance sheet at a higher-than-anticipated level.

Lastly, I’ll put out the simple behavior of rates. I’m surprised the longer end holds up so well, despite all I’ve written, but then I’m forced to confront the Fed as a main contributor, market behavior as the best arbiter of the various inputs and history as a guide.

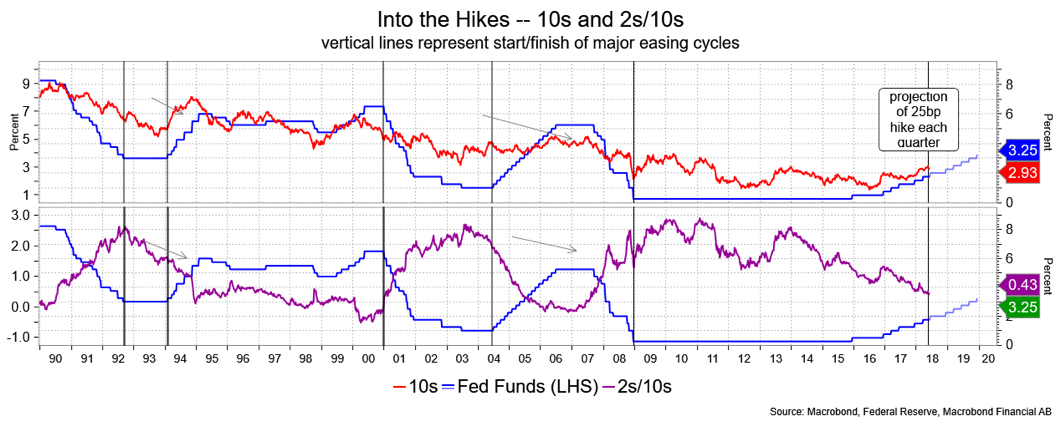

To wit, as the chart below shows, hiking cycles result in flatter curves. The front end responds directly to monetary policy pointing to rising 2-year yields in the coming quarters, while longer yields tend to see their biggest rises at the start of a hiking cycle, which tapers off as the cycle wears on. This doesn’t take away from the risk that 10s break 3 percent with force, and edge to a 3.25 to 3.50 percent area, but it does suggest that they will outperform on the curve and yield levels like that certainly have implications for competitive investments (think asset allocations and foreign bonds) and a dampening impact on economic growth.

In the event the Fed holds to its trajectory—and I think this Fed will do so, in contrast to the more optimistic hopes of the dot plots and the Summary of Economic Projections under Yellen—I think the curve is headed for dead flat to inverted in 12 months’ time.

That is significant. An inverted curve has been a reliable, if not perfect, predictor of a recession 12 to 18 months later. If the course holds, then that bring us right to the November presidential election. A possible restraint on the curve’s behavior is the sheer weight of supply and the projected budget deficit exceeding $1 trillion in 2020. That, I expect, will compel Treasury to issue more longer debt, as well as extend the maturity range to, perhaps, a 40 or longer bond, especially if the curve does what I expect.

By the way, I have to comment that we’re on borrowed time here—or borrowed money. The tax cuts that have so propelled confidence means the economy will have to be paid for. Among other things what surprises me is the lack of fiscal responsibility from the GOP on this matter; I don’t expect it from the Democrats. Chickens will come home to roost, which means perhaps Social Security will come in the form of poultry—or pork—especially if retaliatory tariffs create an abundance of such products domestically.

I take issue with something Daniel Henninger wrote in The Wall Street Journal: “Mr. Trump’s most substantive legislative achievement is the 2017 tax cut. If he announced his retirement next week, history would record that his presidency gave the nation one of the most beneficial economies on record.”

I’m not sure how a tax cut barely six months old can be so construed with no heed paid to the consequences it has on the budget deficit in the days to come (not years, months or weeks). Heck, I could borrow money, spend like a drunken sailor and be called a good old boy, at least until the bills come in. But, channeling the Dick Cheney deficits doesn’t matter—just ask the folks who took out mortgages not too long ago. Deficits don’t matter—until they do, that is.

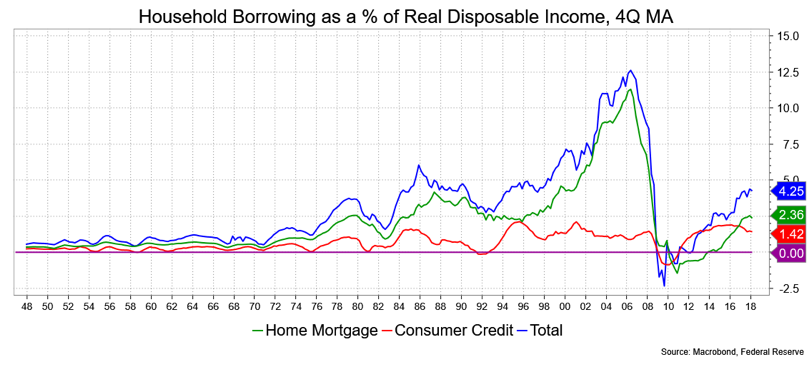

The folks who write The Liscio Report told me that consumers are being very careful about borrowing to spend, which doesn’t suggest great confidence. Household borrowing is up just 1.4 percent as a percentage of real disposable income. That’s a good thing; the recession seems to have had an impact, but it gets back to the use of savings to fuel Retail Sales.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.