(Bloomberg Gadfly) --If you want to know where cryptocurrencies are in their development, keep an eye on fees.

When a new “investment” comes along, investors are often too busy counting their anticipated bounty to care about cost. Shrewd purveyors predictably seize the opportunity to charge excessive fees. But reality inevitably falls short of investors’ expectations, and the focus eventually turns to how much they’re paying to invest.

That’s a short history of stock investing. Investors had little access to stock market data a century ago. They didn’t have the luxury of knowing, for example, that the S&P 500 Index would generate a real return of 7.1 percent annually from 1926 to 2017, including dividends. Or that the index’s real return would fall short of that long-term average 52 percent of the time over rolling 10-year periods.

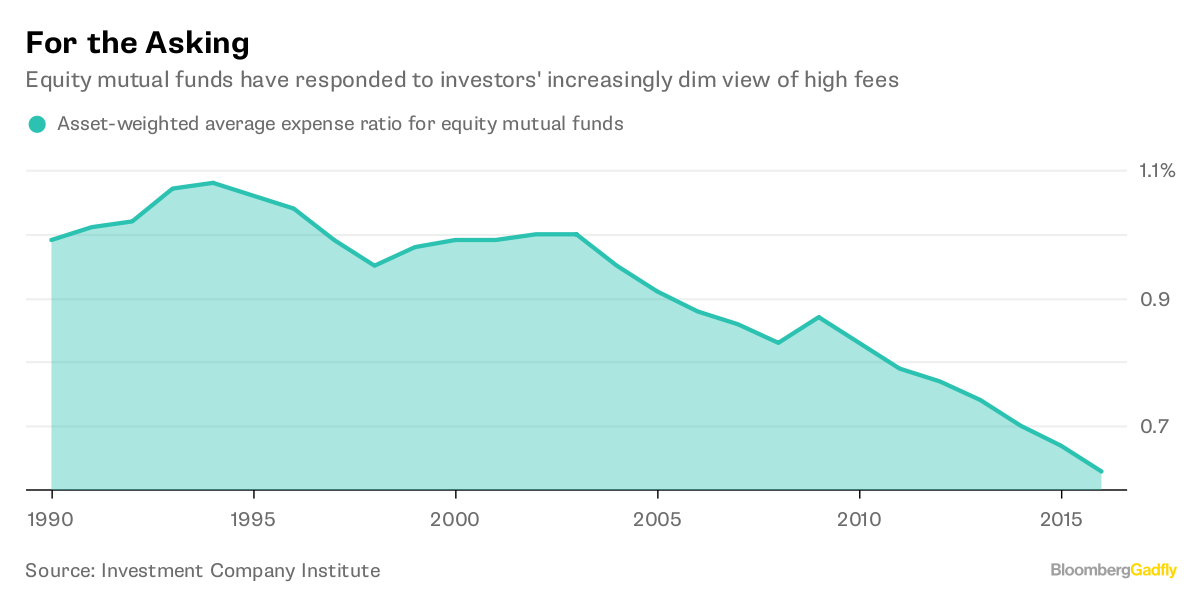

Seeing those numbers, it’s clear that cost is crucial. It’s not surprising, therefore, that investors have demanded lower fees over time. In a 2002 study of trading costs, Columbia professor Charles Jones estimated that the annualized trading costs of NYSE stocks had fallen more than 80 percent since 1900. And in just the last two decades, the asset-weighted average expense ratio for equity mutual funds has fallen 42 percent to 0.63 percent a year in 2016 from 1.08 percent in 1994, according to the Investment Company Institute.

A more recent example is hedge funds. Investors had little data to guide their expectations during hedge funds’ heyday in the 1990s. In the absence of evidence, managers made wild claims about what they could achieve, and credulous investors famously paid them 2-and-20 for the dream -- a 2 percent annual management fee and 20 percent of profits.

Three decades later, it turns out that hedge fund returns were no better than the market’s. The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index has returned 9.9 percent annually from 1990 through February, the longest period for which returns are available, compared with 9.8 percent for the S&P 500.

Granted, hedge funds were also half as volatile as the broad market, and that’s worth something. But how much? Consider that a 9.9 percent annual net return after 2-and-20 implies a gross return of 14.4 percent, or fees of 4.5 percent a year. That’s 90 times more expensive than an S&P 500 index fund.

No wonder investors are pushing back. Credit Suisse Group AG recently conducted a global survey of hedge funds and found that the use of 2-and-20 has fallen 65 percent. It’s likely just the beginning. Providers of exchange-traded funds are rolling out hedge fund strategies for a fraction of the cost. The asset-weighted average expense ratio of long-short ETFs is 0.75 percent a year, according to Morningstar data. That’s a good indication of where hedge fund fees are likely to go.

The evidence is also stacking up for private equity and venture capital, where 2-and-20 is still the norm. And here, too, investors are likely to find the numbers surprising. The median net internal rate of return of the funds in the Cambridge Associates US Private Equity Index averaged 13.2 percent annually for vintage years 1986 to 2015. (The vintage year is the year that the fund first began making investments.)

There’s a catch, however. Unlike an S&P 500 index fund, where the market return is available to all investors, there’s a huge range of outcomes in private equity. The top quartile of funds in the private equity index produced an average net IRR of 21.4 percent, while the bottom quartile eked out 6.6 percent.

The numbers for venture capital are even more eye-opening. The median net internal rate of return of the funds in the Cambridge Associates US Venture Capital Index averaged 11.3 percent annually for vintage years 1981 to 2015. And the range of outcomes was even broader. The top quartile of funds averaged 23.2 percent, compared with just 3.5 percent for the bottom quartile.

Given the additional risks of investing in private equity and venture relative to traditional assets, and the uncertainty around outcomes, I suspect that investors will ultimately balk at paying 2-and-20 for the privilege.

Which brings us back to cryptocurrencies, about which the available evidence is short and useless. Bitcoin’s price history dates to July 2010, and it has returned 392 percent annually through February. There’s no worthwhile information in that number, of course.

But the lack of data allows fantasies to flourish and crypto exchanges to charge whatever they want. Take a look, for example, at the fee disclosure of Coinbase Inc., a popular cryptocurrency exchange with more investors than discount broker Charles Schwab Corp. Coinbase’s fee schedule resembles NYSE trading costs from a century ago. And there are so many carve-outs and disclaimers that it’s impossible to know exactly what the fees are likely to be.

That hasn’t stopped Coinbase’s roughly 13 million users. But someday those users will ask questions and demand a fair shake. That’s when you’ll know that cryptocurrencies are all grown up.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

To contact the author of this story: Nir Kaissar in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]