By Ben Emons

(Bloomberg Prophets) --Last week saw one of the largest increases in volatility since the financial crisis as equities tumbled. Even so, many market pundits say not to worry because the U.S. economy is still expanding at a strong pace. That may be true now, but when volatility exploded in the past the economy usually took a hit.

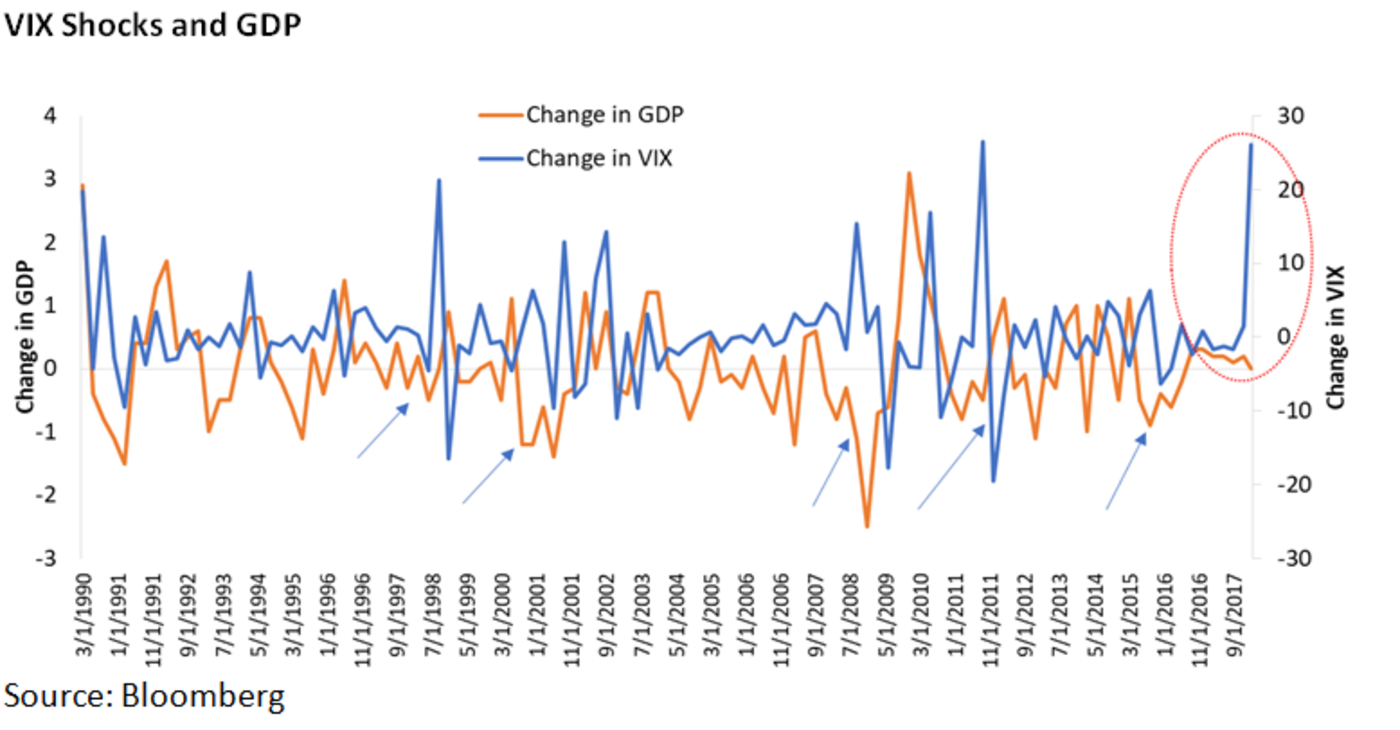

Volatility shocks in 1998, 2008 and 2011 foreshadowed slower growth, or even a contraction, about one to two quarters later. Rising volatility in financial markets can affect confidence, causing companies to delay expansion or other plans and for consumers to cut back on spending. After all, it's hard to know whether the funding you need to pay for such things will be available and at what cost if markets are going haywire.

The latest bout of volatility was triggered by an unexpectedly big jump in average hourly earnings reported by the U.S. government on Feb. 2. The 2.9 percent increase in January from a year earlier was the biggest since 2009, raising concern that inflation is poised to accelerate. That led investors to dump bonds, pushing up yields. The prospect of higher borrowing costs spooked the equities market, leading to a drop in share prices. No less than Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley said last week that a persistent decline in equities could slow spending, but that the recent turmoil hasn't yet changed his outlook.

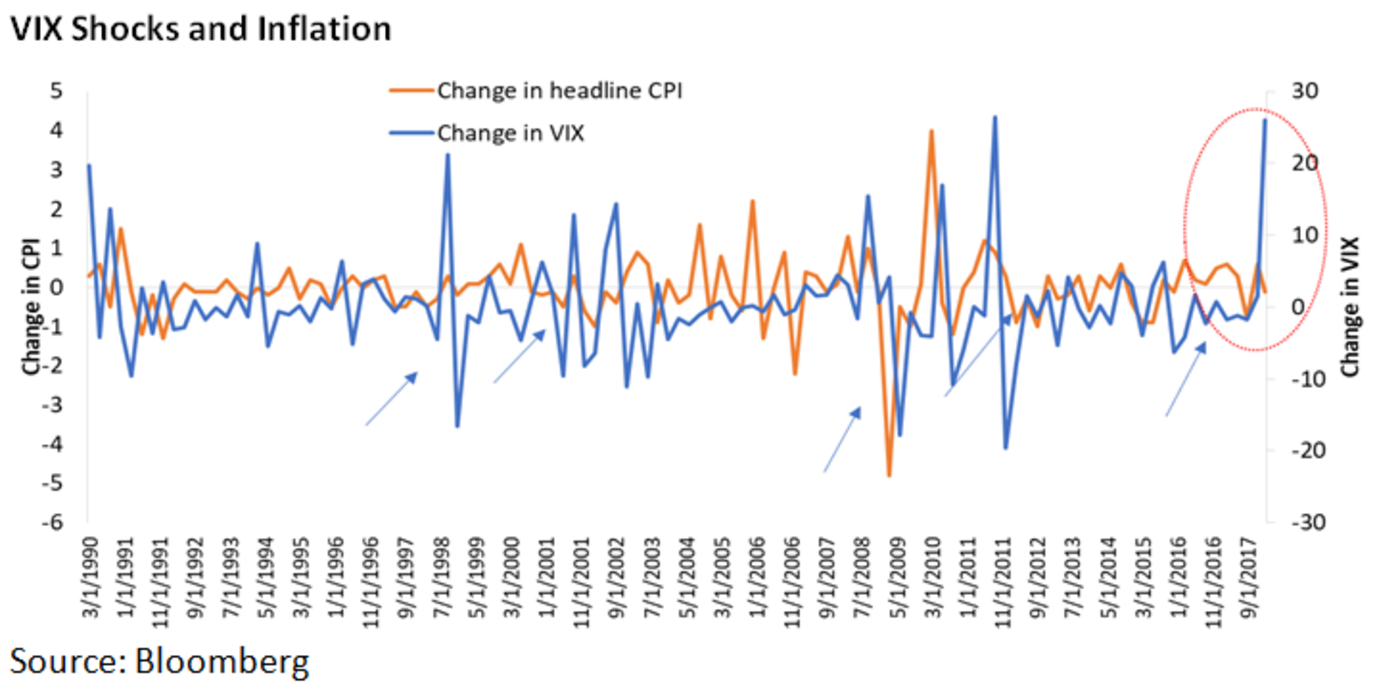

The silver lining is that rising volatility can help temper inflation. When the Cboe Volatility Index, or VIX, spiked higher in 2008 and 2011 to reach levels around 30 and 40 -- like now -- the economy slowed and inflation moderated. It's notable that inflation expectations as measured by breakeven rates on Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities declined a bit last week as volatility surged. A gain in the dollar also weighed on breakeven rates, which are essentially what bond traders expect inflation to be over the life the securities.

A stronger dollar, in turn, weighed on oil prices, which broke below $60 a barrel for the first time since December. If market expectations of inflation continue to drop, the Fed might have a harder time boosting inflation toward its 2 percent target, opening the door to a slower pace of interest-rate increases.

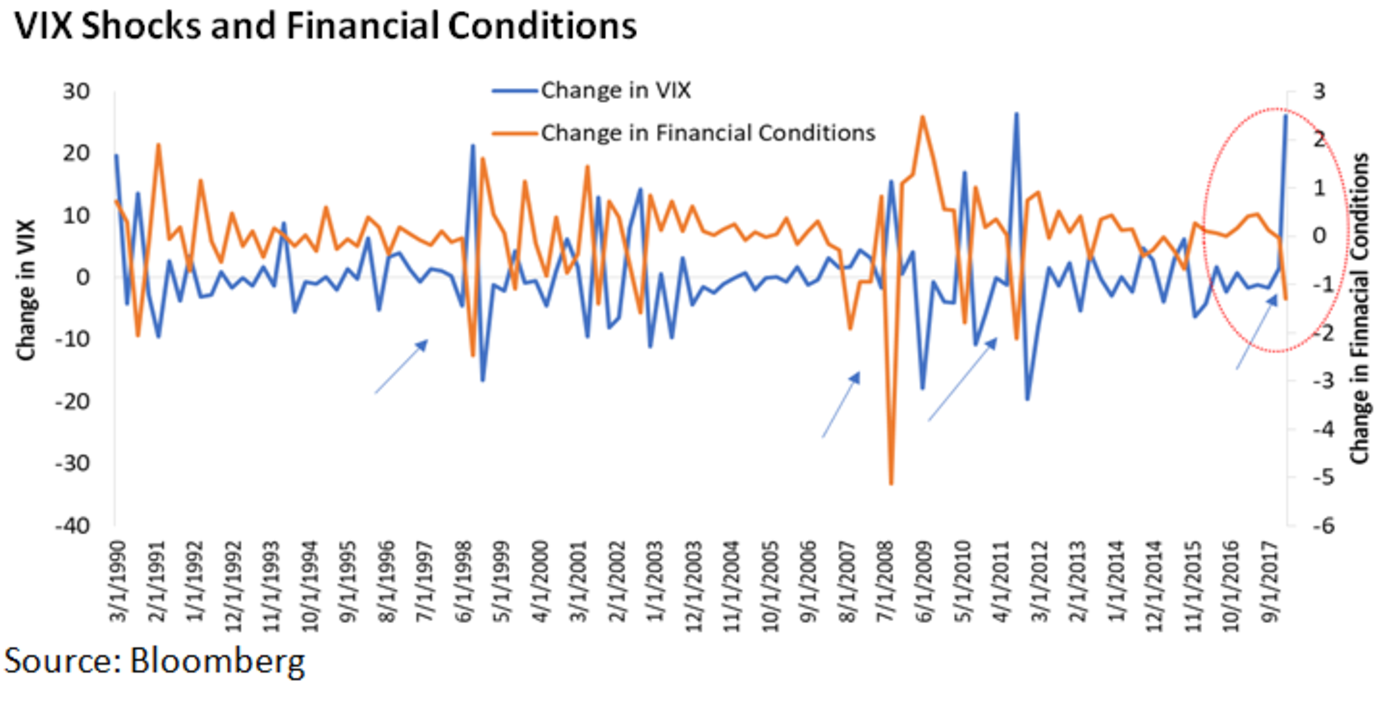

Rising volatility also tends to cause tighter financial conditions. In fact, the latest declines in financial condition indexes that coincided with last week's jump in volatility look significant when compared with 2008, 2011 and 2015. The Fed is an astute observer of financial conditions, which have guided its decision making in the past. Such was the case in late 2015 when credit markets experienced a crunch. At the time, the market expected the Fed to boost rates at least three times in 2016. The Fed, though, ultimately became more dovish and only raised rates one time at the very end of 2016.

Expect the latest volatility shock to have an impact on the broader economy as financial conditions tighten and confidence dips. The flattening of the Treasury market yield curve and weakening of the dollar over the past year were signs that a slowdown was probably already in the cards. The data in the next few months will reflect what happened last week and that could change the narrative of the goldilocks environment from the past year.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Ben Emons is chief economist and head of credit portfolio management at Intellectus Partners LLC. The opinions expressed are his own.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Emons at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view