By Scott MacKillop

Over the last few years numerous people have said or written that asset management is becoming a commodity. Some of these people are commentators who I respect very much. But I think this view is demonstrably wrong and dangerous to the well-being of investors.

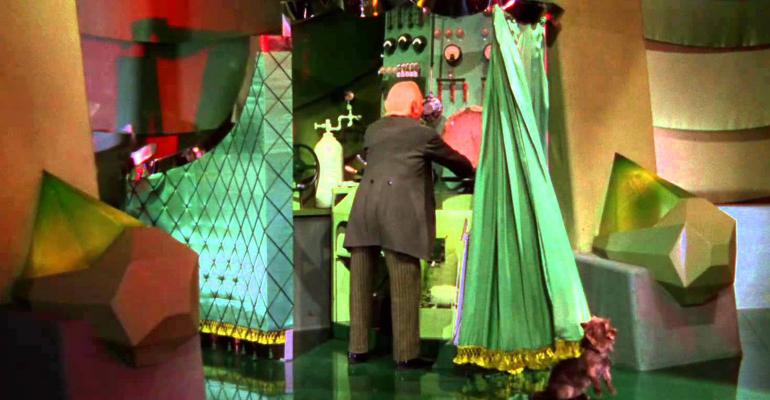

The “asset-management-is-a-commodity” mantra became popular as the current crop of robo advisors emerged and began to gain traction. Apparently, the fact that a machine could create and manage portfolios evoked the idea in some observers that asset management was, in fact, a mindless endeavor devoid of skill, art or judgment. When the curtain was whisked away, there was no Wizard—only a warm metal box that hummed and glowed faintly as it optimized, rebalanced and tax-loss-harvested millions of portfolios with the greatest of ease.

All this was happening at roughly the same time active managers were taking it on the chin in study after study assessing whether they added any value at all. These studies increasingly portrayed the active camp as a bunch of hairless runts who couldn’t hope to compete with the lean, mean passive machine. The only question was whether they were greedy, deceptive weasels or simply well-intentioned, but clueless practitioners of an ancient art.

The fact that robos offered their services at dramatically lower prices than human managers also contributed to the idea that asset management was quickly becoming a commodity. Sugar is cheap and it’s a commodity. Soybeans are cheap and they’re a commodity. Sand is cheap and it’s a commodity. Now asset management is cheap so it must be a commodity too. A portfolio was really no different than a bag of sugar, a hill of beans or a dump truck full of sand.

This is shallow thinking. The fact that something formerly done by hand can now be done by machine does not make it a commodity. Medical procedures that were in the past performed by doctors are now routinely performed by machines. A skilled operator is still required for the machine to be able to produce a satisfactory outcome. A bear can ride a bicycle, but you’ll never see one compete in the Tour de France, even if it passes the drug test.

It also makes a huge difference who built and programed the machine. The fact that a machine can do something does not mean that it can do it well. There are plenty of quant strategies and market timing systems that have famously flamed-out. These were machine-driven programs that failed to produce acceptable outcomes. Remember Long-Term Capital? Garbage in, garbage out. Where quality is a differentiator, commoditization cannot occur.

The fact that a good or service declines in price does not make it a commodity either. Many factors can affect pricing, including supply and demand, competition, deregulation and improvements in technology. And the prices of commodities can rise based on these same factors. So automatically equating falling prices with commoditization is misguided.

Computers are much cheaper than they were a few years ago, but they are not commodities. Just ask a Mac user to switch to a PC if you don’t believe me. Cell phones are cheaper too, but I’ll never convince my wife that my Samsung is better than her iPhone.

Sometimes even as the price of a product or service declines, its features, benefits and user experience improve. This is clearly the case with computers and cell phones. These improvements become the basis for differentiation, not commoditization. For example, the camera on my Samsung is way better than the camera on my wife’s iPhone. Just sayin’.

Merriam-Webster defines the term commodity as, “a mass-produced unspecialized product” or “a good or service whose wide availability leads to smaller profit margins and diminishes the importance of factors…other than price.” So the hallmark of a commodity is that it lacks differentiating features other than price. A bag of sugar from C&H is functionally the same as a bag of sugar from Domino. Beans are beans. Sand is sand.

Calling asset management a commodity suggests that it makes no difference who you purchase the service from as long as the price is low. This is a dangerous idea that could harm and mislead investors. Asset management is not all the same. It makes a big difference what products you use and how you combine them in a portfolio. The fact that computers are now more involved in the process does not make asset management a homogeneous commodity.

If you disagree, consider the following facts, which were culled from the Morningstar database. All numbers are as of June 30, 2017. I have taken the liberty of eliminating some obvious outliers that would have unfairly skewed the results (but made my point more strongly).

- The 5-year annualized returns for US Large Blend actively managed mutual funds ranged from a high of 17.22% to a low of 5.21%. Internal expenses ranged from 2.16% to 0.15%.

- The 5-year annualized returns for US Large Blend ETFs ranged from a high of 16.73% to a low of 12.18%. Internal expenses ranged from 1.25% to 0.03%.

- The 5-year annualized returns for US Large Blend index mutual funds ranged from a high of 16.51% to a low of 12.31%. Internal expenses ranged from 1.57% to 0.01%.

- The 5-year annualized returns for managed ETF portfolios with an equity range of 50% to 70% ranged from a high of 13.69% to a low of 3.35%.

Clearly there are large differences in performance, even among apparently similar investment products. It obviously matters which humans are making the decisions. They all have access to computers, but their use of them produces widely disparate results.

There is also an astonishingly wide range of internal expenses among these products. These differences alone could cost an investor with a modest sized investment portfolio hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of a 20 or 30-year investment horizon.

Even “passively” managed portfolios can produce wide variances in performance based on the decisions humans make in constructing and managing them. What asset classes will you use? How will you allocate them? Which products will you use in implementing the asset allocation strategy? What rules will you use in rebalancing the portfolio? These decisions matter.

The performance generated by robo advisors also shows a similar pattern of dispersion. Condor Capital has been tracking the performance of a number of prominent robos and the results show variations in the investment results achieved by these firms. Ultimately, their performance, too, is determined by the inputs, algorithms and parameters created by humans.

Seemingly small differences in performance can significantly impact the financial security of an investor over time. A $1 million portfolio that achieves a 6 percent return over 25 years will produce a $4,291,871 retirement fund for the investor. The same sized portfolio that achieves a 7 percent return over the same period will produce a $5,427,433 retirement fund. The $1,135,562 difference could fund years of additional retirement for the investor. Outcomes matter.

We would all be well advised to view asset management as a highly-differentiated field where the choices we make produce huge differences in the outcomes we experience. Asset management is nothing like a bag of sugar, a hill of beans or a truck-load of sand. Regardless of how much we rely on computers to help us manage portfolios, asset management is ultimately driven by human decisions. The quality of those decisions greatly impacts investor well-being.

Scott MacKillop is CEO of First Ascent Asset Management, a Denver-based firm that provides investment management services to financial advisors and their clients. He is a 40-year veteran of the financial services industry. He can be reached at [email protected].