By Hugh Son

(Bloomberg) --Call them cyborgs. Morgan Stanley is about to augment its 16,000 financial advisers with machine-learning algorithms that suggest trades, take over routine tasks and send reminders when your birthday is near.

The project, known internally as “next best action,” shows how one of the world’s biggest brokerages aims to upgrade its workforce while a growing number of firms roll out fully automated platforms called robo-advisers. The thinking is that humans with algorithmic assistants will be a better solution for wealthy families than mere software allocating assets for the masses.

At Morgan Stanley, algorithms will send employees multiple-choice recommendations based on things like market changes and events in a client’s life, according to Jeff McMillan, chief analytics and data officer for the bank’s wealth-management division. Phone, email and website interactions will be cataloged so machine-learning programs can track and improve their suggestions over time to generate more business with customers, he said.

“We’re desperately trying to pattern you and your behavior to delight you with something you may not have even been asking for, but based on what you have been doing, that you might find of value,” McMillan said in an interview. “We’re not trying to sell you, we’re trying to find the things you want and need.”

Faced with competition from cheaper automated wealth-management services and higher expectations set by pioneering firms like Uber Technologies Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., traditional brokerages are starting to chart out their digital future. It turns out that the best hope human advisers have against robots is to harness the same technologies that threaten their disruption: algorithms combined with big data and machine learning.

The idea is that advisers, who typically build relationships with hundreds of clients over decades, face an overwhelming amount of information about markets and the lives of their wealthy wards. New York-based Morgan Stanley is seeking to give humans an edge by prodding them to engage at just the right moments.

“Technology can help them understand what’s happening in their book of business and what’s happening with their clients, whether it be considering a mortgage, to dealing with the death of a parent, to buying IBM,” McMillan said. “We take all of that and score them on the benefit that will accrue to the client and the likelihood they will transact.”

Morgan Stanley will pilot the program with 500 advisers in July and expects to roll it out to all of them by year-end.

Additional high-tech tools are coming: McMillan and others are working on an artificial intelligence assistant -- think Siri for brokers -- that can answer questions by sifting the firm’s mountain of research. (The bank produces 80,000 research reports a year.) The brokerage also is automating paper-heavy processes like wire transfers and creating a digital repository of client documents, such as wills and tax returns. Established advisers tend to be older, so Morgan Stanley is hiring associates to train those who need help.

The technology means that for the first time in decades, the balance of power between financial advisers and their employers may shift. For years, top advisers could command multimillion-dollar bonuses by jumping to a competitor. That slowed to a crawl this year because of regulatory changes, and now the technological push will further the trend, according to Kendra Thompson, a managing director at Accenture Plc.

Bonuses Obsolete

Backed by a firm’s algorithms, “advisers are going to be part of a value proposition, rather than the service conduit for the industry,” Thompson said. “The cutting of the bonus check, it’s nearly over.”

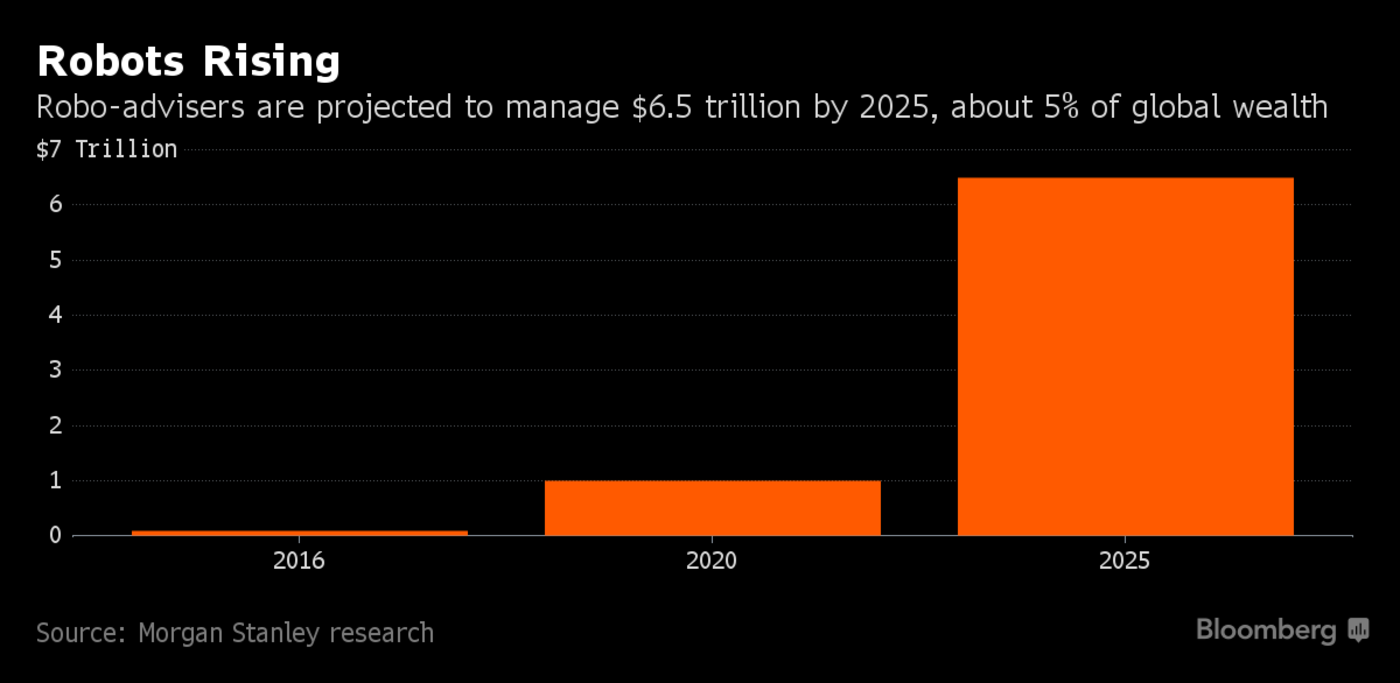

Morgan Stanley isn’t swearing off robo-advisers, either. It plans to release one in coming months, along with rivals Bank of America Corp., Wells Fargo & Co. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. The technology was pioneered by startups Wealthfront Inc. and Betterment LLC and went mainstream at discount brokers Charles Schwab Corp. and Vanguard Group Inc. Robos could have $6.5 trillion under management by 2025, from about $100 billion in 2016, according to Morgan Stanley analysts.

An in-house robo-adviser and a learning machine that acquaints itself with rich clients might alarm advisers who plan to keep working for decades. McMillan is adamant that the flesh-and-blood broker will be needed for years to come because the wealthy have complicated financial planning needs that are best met by human experts.

“When I talk to financial advisers, they’re always like, ‘Is this going to put me out of business?’” he said. “That’s always the big elephant in the room. I can tell you factually that we are a long ways away from that.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Hugh Son in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Peter Eichenbaum at [email protected] David Scheer, Dan Reichl