Advisor beware: If you have high-net-worth clients who own life insurance in their own names, they could face an unexpected estate tax hit should the Bush tax cuts of 2001 be allowed to sunset in 2011 (although “die” seems like the more appropriate word). But guess what? To avoid the tax hit (and a potential malpractice suit against you), you should act now—by December 31 of this year—to remove the policy from their estates.

As you know, among other things, the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (“EGTRRA”) significantly raised the value of an estate before it was subject to the federal estate tax; and when the estate did qualify, it lowered the tax rate burden. The legislation resulted in the vast majority of Americans not being subject to a federal estate tax (or, as the Republicans like to derisively call it, the death tax). In fact, in 2008, it is estimated that less than one-third of 1 percent of all estates will pay a federal estate tax. But Washington is mired in a squabble over EGTRRA (and AMT reform, among other things), and few expect any legislation to move until after the 2008 presidential election. So you have to plan for the worst and hope for the best now, lest some of your clients’ estates be susceptible to higher federal estate taxes.

Particularly vulnerable are unmarried clients with current taxable estates over $1 million and married couples with current taxable estates over $2 million. Further complicating the issue, if your clients live in one of the 23 states (and also D.C.) that no longer use the federal estate tax as the basis for their own estate tax (“decoupled,” in tax jargon), the thresholds amounts for inclusion are even smaller. For example, the threshold for state death taxes is $338,000 in Ohio, $675,000 in New Jersey and $1.0 million in New York and Massachusetts.

Because no one knows what Congress will ultimately do, to save any vulnerable clients, you, the advisor, are simply going to have to assume that “EGTRRA” is going to die. If that happens, the federal estate tax exemption equivalent drops to $1 million per decedent. Moreover, the federal estate tax rate will change from a flat 45 percent (from 2007 to 2009) to a range of 41 percent to 60 percent in 2011. In 2010, current law says that the federal estate tax will be eliminated for that year, but most tax attorneys expect Congress to adopt stop-gap legislation – possibly carrying the 2009 rules across 2010. These two changes, when coupled with the continuing appreciation in the value of a client’s estate, could cause a substantial unexpected increase in estate taxes for the unwary client.

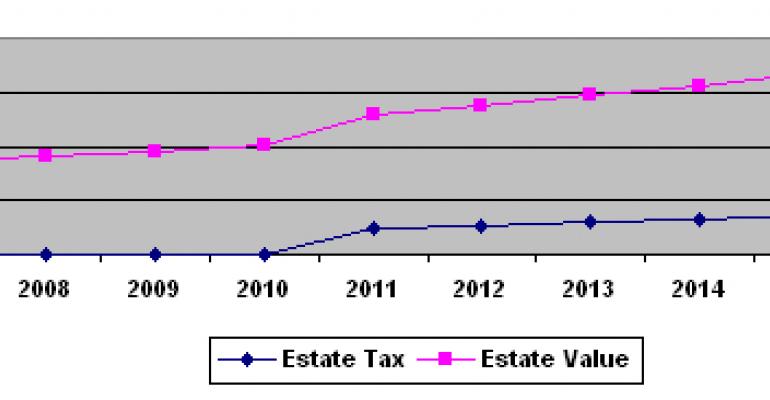

Example: Assume in 2007 that a widow has an estate of $1 million, growing at 8 percent annually. The client also owns a life-insurance policy with a death benefit of $750,000. The following table shows the impact for each possible year that the client dies.

Even though the estate continues to grow, the net percentage that passes to family decreases—as an increasing part of the estate is subject to a higher estate tax rate. (See below.)

However, if the existing life insurance policy is gifted to family members or to a family trust, the 3-year “contemplation of death” rules of code section 2035(a) means that planning for the gift of life insurance should occur by December 31, 2007 (i.e., looking back three years from January 1, 2011). Thus, this client cannot take a “wait-and-see” attitude. This client needs to consider—again, before the end of 2007—how to get the life insurance out of her taxable estate or consider purchasing a new policy and have the policy owned from issuance date by one or more family members or an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT).

Even if the current life insurance is moved out of the taxable estate, there remains an increasing estate-tax cost (see the above chart) after 2011. If her long-term insurability is questionable, she should consider obtaining the insurance today in a non-taxable ownership form to make sure it can’t be included in her taxable estate.

Married Couples

For married couples the issues are a bit more confusing. Because the passage of assets to a spouse generally creates no estate-tax liability (but the assets are potentially taxable at the second death), timing and order of death can create some unexpected results.

Example: Assume a married couple in 2008 has a $1.6 million estate growing at 5 percent annually. One of the spouses owns a $1 million life insurance policy on that spouse’s life. All other assets are evenly owned. One spouse dies in 2008, while the other dies in 2011.

If the insured spouse dies in 2008, no estate taxes would be due on the couples’ combined estates. In 2008 the insured spouse’s estate is $1.8 million (when the exemption is $2 million) and the uninsured spouse’s estate is $926,000 in 2011(when the exemption could be $1 million) – resulting in no estate tax with proper planning. However, if the insured spouse dies in 2011, the insured spouse’s taxable estate would be $1,926,000, creating a federal estate tax of almost $402,000.

Example: A husband in a second marriage owns $2 million in assets and a $1 million life insurance policy. The wife has $600,000 in assets. In 2007 the husband gifts the life insurance to an ILIT and then dies in 2008. At the husband’s death in 2008, the $1 million life insurance policy is pulled back into the insured’s estate. Under the terms of his will, $2 million goes into a By-Pass trust and $1 million passes to a QTIP marital trust. The assets grow at 5 percent annually.

At the wife’s death in 2011, her personal assets are worth approximately $695,000. The marital trust assets are worth approximately $1,158,000, creating a taxable estate of $1,853,000 and a federal estate tax of approximately $369,000.

Clients with estates (including life insurance) over $1 million should not take a wait and see attitude. If clients become incapacitated before 2011 (and therefore cannot change their estate planning documents), die with their present plan in place or become uninsurable, the failure to address the sunsetting of EGTRRA could create a significant increase in estate taxes, and a malpractice case against the clients’ advisors. But increased federal estate taxes may not be the worst news. In states that have decoupled (i.e., a state that no longer bases its state death tax on the federal state death-tax credit) from the federal estate tax, planning will be even more confusing in 2011 (for instance, the state estate-tax exemption in Ohio is only $338,000).

For more, see www.scrogginlaw.comJOHN J. SCROGGIN is an attorney, former CPA and a member of the law firm of Scroggin & Company, P.C. in Roswell, Georgia. Scroggin is the editor of the NAEPC Journal of Estate and Tax Planning and is a member of the Board of the National Association of Estate Planners and Councils.