By Krishna Memani

It is an odd title shortly after the Trump administration reached a revised NAFTA deal and markets are breathing a sigh of relief. This is especially true because the primary reason for the cautionary tone is driven by trade and tariffs.

That the Trump administration reached a deal with Mexico and Canada, after a lot of huffing and puffing, of course, is not that big a surprise. Given their size relative to their much larger neighbor, their heavy mutual economic interdependence on the United States and each other, and their lack of global political ambitions, it’s not surprising that Mexico and Canada finally found a way of honorably accepting a new trade agreement rather than have it crammed down their throats.

China: The Real Elephant in the Room

But, resolving the trade conflict with China—the real elephant in the room—is not going to be that easy. While I had thought, or more precisely, hoped, that the trade issues with China might start getting resolved by the midterm elections, that possibility is rapidly fading. More likely than not, it now seems, the United States and China will have to call each other’s bluff before a path to resolution can be found.

Unfortunately, if we don’t get to it sooner rather than later, the consequences of this brouhaha are likely to be very negative for both sides. And the markets will be the collateral damage in that unnecessary and undesirable outcome.

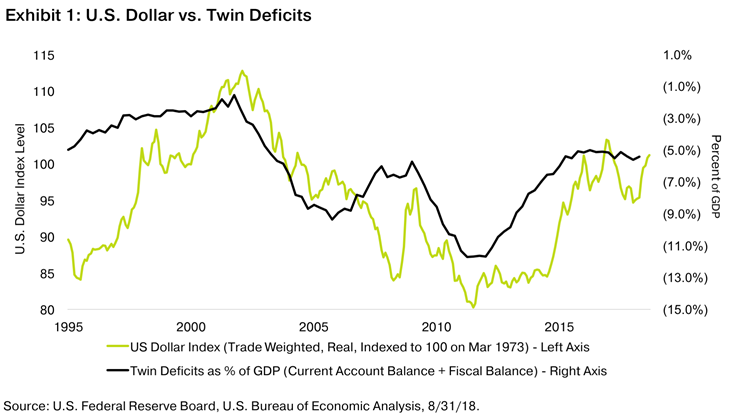

We can, of course, debate the cost benefits of trade until the cows come home. But, to be perfectly clear, if the objectives of the bilateral or multilateral trade deals or tariffs are to reduce trade and the current account deficit, and save U.S. jobs in the process, they’re unlikely to meet those objectives. There is a simpler, but not necessarily painless, way to reduce the U.S. trade deficit rather than beating up on our trade partners—reduce the U.S. fiscal deficit.

However, the fiscal deficit is expanding, not contracting. Unless the U.S. savings rate picks up, the only rational way to fund the fiscal deficit is by importing foreign savings through trade. After all, it’s a basic accounting identity that cannot be violated. In essence, U.S. consumers and businesses buy products and services from around the world and give them dollars in return. Those foreign sellers of goods and services exchange the dollars at their central banks for their local currency. The central bank, in turn, invests those dollars in U.S. Treasurys, effectively financing the U.S. fiscal deficit. However, increasing domestic savings too much, too quickly, may actually lead to either the end of the expansion due to reduction in demand or through rapidly rising inflation, thus forcing the U.S. Federal Reserve’s hand into aggressive tightening.

Fed Seems More Committed to Rate-Raising Path

The Fed has become increasingly important now that the asynchronous nature of policymaking in the U.S. is becoming clearer. On the one hand, the U.S. Congress is trying to stimulate the economy by passing tax cuts, and on the other, implementing tariffs. At the same time, the Fed is becoming far less nuanced in its decision-making and even more committed to its rate-raising path.

If you don’t believe me on the Fed front, just read the Sept. 28 speech by New York Fed President and CEO John C. Williams at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. It’s a fascinating speech for everyone, not just Fed geeks.

After talking about artifacts like R-star*—the presumed neutral rate of interest—Williams, and I am assuming the whole Fed, is giving up on the entire concept of R-star altogether. This is very important, as we all assumed that the Fed would somehow stop when it got to the R-star—say 3 percent in today’s context. But that may not be a good assumption anymore.

Williams seems to be saying that the markets cannot assume that the Fed will stop when it gets to R-star. Instead, if the data warrants it, Fed policymakers will just keep going. Taken too far, given the current growth and inflation trajectory, the Fed is effectively liberating itself, the markets could conclude, of its entire post-Financial Crisis burden of careful monetary policy, lest they kill the current cycle.

For now, none of this matters. The U.S. economy is doing fine, inflation is under control, Fed policies don’t seem to be biting, and the markets are taking it all in stride.

Quick Trade Win over China Doubtful, Dangerous

But it’s not too difficult to imagine a scenario where we have 25 percent tariffs on all imports from China, political rhetoric picks up, inflationary pressures rise, and the Fed is forced into acting more aggressively than it should or would have in the absence of such shocks. The U.S. economy and markets will not be too happy then.

I still believe and hope, the trade wars—at least the only trade war that matters, between the United States and China—get resolved soon. That would imply the current cycle may have at least a few more years to run.

However, given the political rhetoric and relatively easy trade “victory” over Mexico and Canada on the NAFTA front, the Trump administration may be tempted to go full on versus China. A quick victory on that front is far less assured. And the administration would be truly playing with fire indeed.

* R-star is the inflation-adjusted, short-term interest rate consistent with the full use of economic resources and steady inflation near the Fed’s target level.

Krishna Memani is CIO at OppenheimerFunds.