By Charles Stein

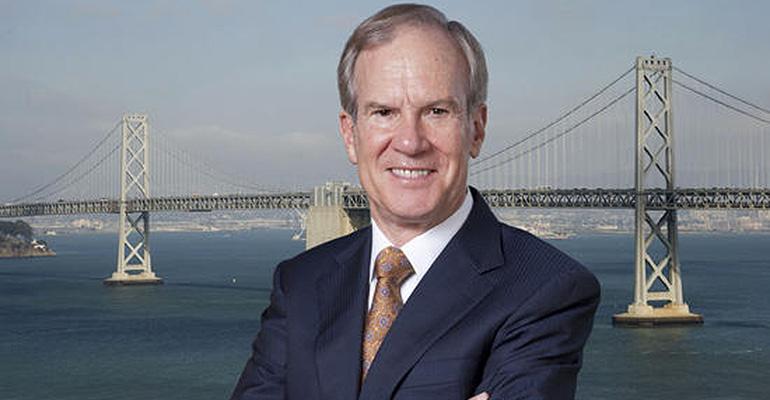

(Bloomberg) --Jerome Dodson, a pioneer in socially responsible investing, was feeling the pressure. Investors in his $3.7 billion Parnassus Endeavor Fund were urging him to dump Wells Fargo & Co. last September as the bank’s phony-account scandal sent its shares skidding.

Dodson balked. The company’s portrayal in the media was too harsh, he said, noting its charitable giving and efforts to promote women as branch managers. Ethics aside, it’s hard to argue with the decision: The stock has surged 36 percent from its low at the time, triple the gain of the broad market.

“I am not a zealot,” Dodson said in a recent interview at his midtown Manhattan apartment overlooking the city. “My politics are modestly left-of-center. I am a normal American guy who believes in capitalism.”

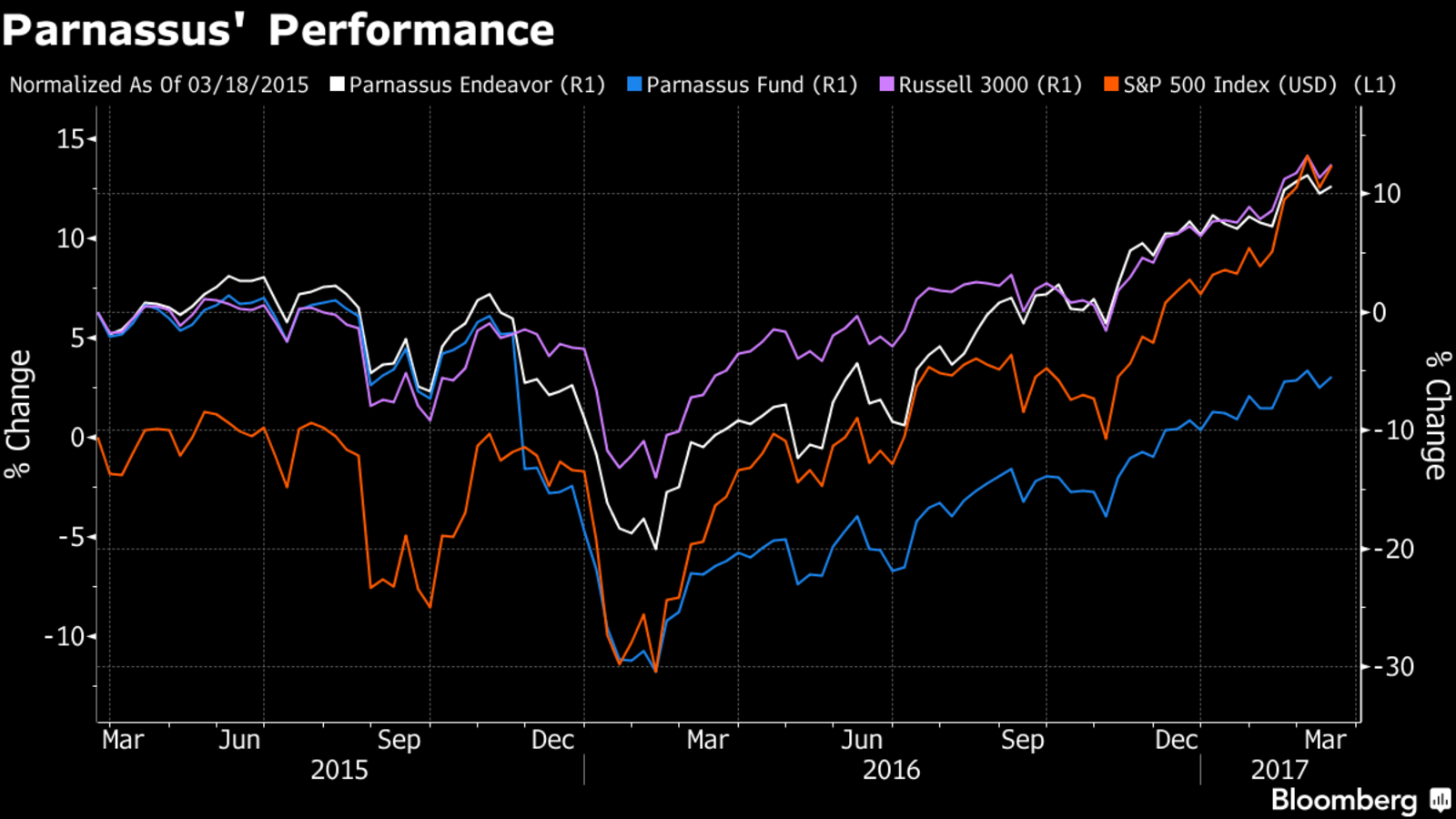

Dodson, 73, says he gets an edge on the investing crowd by favoring companies that treat their employees and the environment well, yet he mostly credits buying low and selling high. His formula -- one part idealism, two parts Graham and Dodd -- has produced 13 percent annualized returns over the past decade, versus 8 percent for the S&P 500 Index. Endeavor tops not just the socially responsible niche but all U.S. diversified equity mutual funds with at least $1 billion, according to Bloomberg data through March 15.

The thin, boyish-looking money manager is preparing to step down in mid-2018 as chief executive officer of San Francisco-based Parnassus Investments, the firm he founded in 1984. Dodson, who calls himself a student of value investing legends Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, vows to keep running Endeavor, whose success has helped spark a surge in assets at the firm.

No Smoking

An affable Midwestern native who lives most of the time in California’s Bay Area, Dodson readily admits to making missteps. Endeavor is trailing 82 percent of large-cap growth rivals this year, hurt by a roughly 4 percent decline in its biggest holding, biotech giant Gilead Sciences Inc.

Dodson acknowledges he could have sold another top holding, Whole Foods Market Inc., before the share price fell by almost half over the past two years, but he underestimated the growing competitive pressure in the natural foods business.

“How embarrassing,” he said.

Like other funds carrying the label of socially responsible, or ESG -- environmental, social and governance -- Endeavor favors what it considers good corporate citizens. For Dodson, that means avoiding companies in businesses including cigarettes, alcohol and fossil fuels.

Endeavor was started in 2005 as the Workplace Fund, premised on the theory that the best places to work would also make the best investments. Dodson, whose ideas are drawn from the firm’s research as well as Fortune’s annual ranking of prized employers, believes conscientious bosses attract motivated workers. He started screening out oil, gas and coal stocks in 2014, reasoning that companies respecting the planet will avoid problems such as fines.

In the aggregate, large-cap ESG funds have performed virtually the same as their conventional peers over the long haul, Morningstar Inc.’s data show.

Home Runs

For Endeavor, “It is hard to know how much the social tilt has contributed to performance,” said Morningstar analyst Wiley Green. “What you can say is that Dodson has picked great companies and knocked the ball out of the park.”

Dodson tries to buy strong companies for discounted prices -- at least one-third below their true worth -- and hang on through tough times.

“It’s emotionally difficult to invest in a stock after the company has suffered a big setback,” he wrote in a February letter to clients. “It is also difficult for me to do that, but I’m a pretty even-tempered person.”

Dodson bought shares of Charles Schwab Corp. in 2012 when the financial-services giant traded for about $13, figuring it was punished by abnormally low interest rates and would eventually rebound. It’s now above $43.

As investors industrywide flock to social-impact funds, Dodson isn’t sure whether high-mindedness or performance-chasing is spurring inflows to his firm. Endeavor shareholders added more than $1 billion in the first two months of 2017, Bloomberg estimates.

Early Jitters

Mitchell Kraus, a financial adviser in Santa Monica, California, has long utilized the $944 million Parnassus Fund, another top performer Dodson manages, for his ESG-oriented clients.

“With recent performance, I wish I used it for all my clients,” Kraus said.

Dodson is something of an overnight success, albeit delayed. When he opened Parnassus, he had an MBA from Harvard, $100,000 in savings and experience running a California bank that financed solar-energy projects. He needed $30 million in assets to make the business viable and wasn’t sure he’d get there before his cash ran out.

“I was over 40, had four kids and worried that no one would hire me,” Dodson recalled.

The firm grew slowly.

“People thought socially responsible investors were do-gooders doomed to fail,” he said.

Buffett Benchmark

Today, Parnassus has a staff of 45 and assets have swelled to $23 billion from $5 billion in 2011. Dodson shakes his head.

“I never thought we would get to a billion,” he said.

Portfolio manager Ben Allen, who is also the firm’s president, will become CEO next year at age 41. Allen started at Parnassus like almost all its managers: hired by Dodson as an intern.

Dodson doesn’t envision hiring a successor at the Endeavor fund any time soon.

“If you’re wondering about a precedent, I would like to point out that Warren Buffett is still managing Berkshire Hathaway and he is 86 years old,” he wrote in last month’s letter. “I’m only 73, so I have a long way to go.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Charles Stein in Boston at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Margaret Collins at [email protected] Josh Friedman, Alan Mirabella