By Eric Balchunas

Be careful what you wish for. While it is tempting for fund managers to root for a downturn so they can show investors why a human hand is better than the "dumb" passive index mutual funds and exchange-traded funds that investors have flocked to, it would actually be the worst possible situation for them and likely result in a messy and hurried consolidation of the entire industry like nothing we’ve seen before.

First, it would severely damage the one thing that has protected active managers against the $7 trillion shift into low-cost index funds and ETFs: a big asset base. A big base in a bull market is not just a bulwark against outflows, it is a virtual money printing machine. In the past four years almost $1 trillion has come out of active equity mutual funds, including in 34 out of the last 35 months, yet their assets have increased by about $1 trillion over that time period to $6.5 trillion. So, despite losing about 20 percent of their deposits, they saw fee revenue increase from about $40 billion a year to $45 billion thanks to epic stock market returns.

Now, let’s say we saw a 2008-style 50 percent drawdown in stocks. The money-printing machine that giveth would taketh away as the $45 billion would drop to about $23 billion. And that's before accounting for any outflows.

Speaking of outflows, the second whammy would come courtesy of panicked investors. In 2008, active mutual funds saw $259 billion in outflows. That translates into $500 billion today since they have roughly double the assets. It's likely that many investors are in these funds only because they are sitting on unrealized capital gains and don’t want the tax bill. A bear market would give them an excuse to get out, possibly taking some $1 trillion with them.

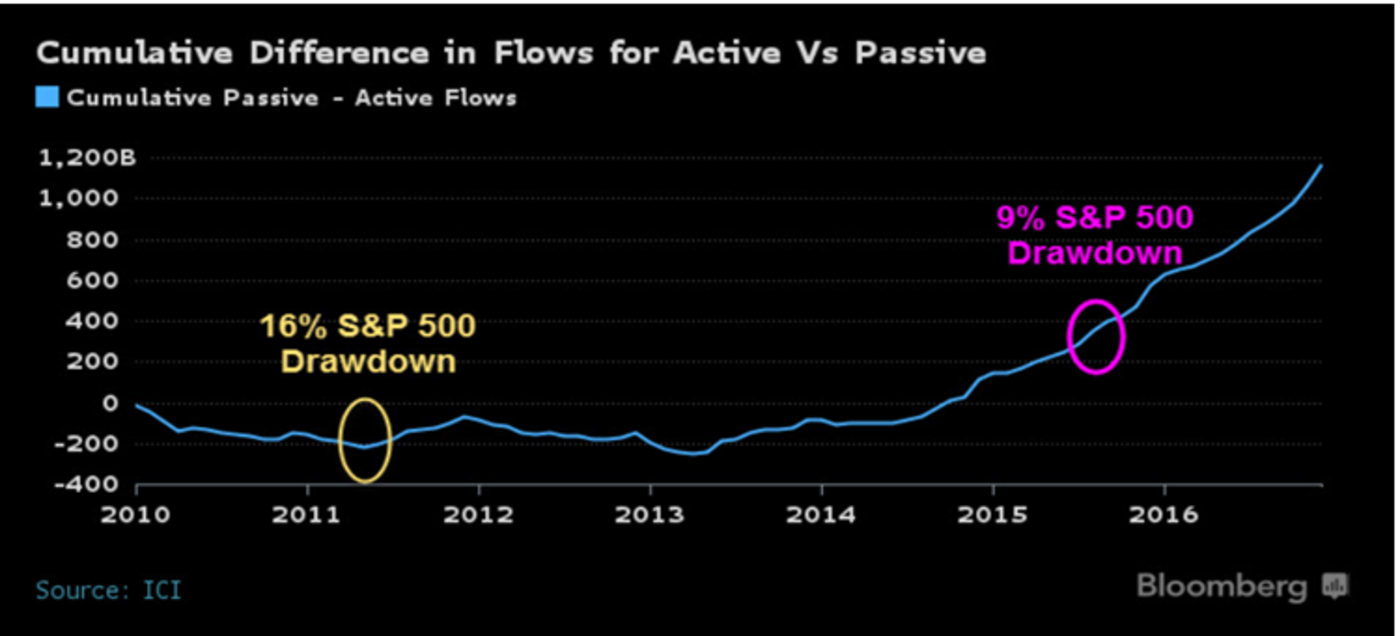

As if that weren't enough, the secular trend of money seeking the lowest fees possible wouldn't stop in rough markets. Each time there’s been a significant drawdown in the market, the ratio of inflows into passive funds versus active increased. In the January through March period, 90 percent of all new cash went to passive funds that charge 0.20 percent or less as the S&P 500 Index had its first down quarter since 2015. In other words, people tend to pull money out of both active mutual funds and ETFs 1 during a downturn, but they when they decide to get back in the market, their money tends to flow into dirt-cheap index products.

It's possible some active funds will outperform in a brutal drawdown and attract large sums of money, but it’s highly unlikely because even those active equity funds that are outperforming are feeling outflow pressures. They are in a tough spot because their clients will pull their money if the funds take more or less risk and are wrong. Managers are stuck playing a game of staying close to their benchmarks if they want to maintain or gain assets. On flip side, they tend to get blamed if they don’t sidestep the downturn. It’s a wicked conundrum.

Sure, it's possible active managers can survive and thrive, especially those focused on the bond market, where the skillset is a bit different. That said and based on the data -- both hard and anecdotal -- I don’t see a scenario where investors decide to go back into high cost active funds, especially those focused on equities. 2 As such, the other side of a bear market will likely create a new equilibrium where passive is 50 percent to 60 percent of all fund assets (currently it is 35 percent).

The active money management industry will have to consolidate -- and depending on how fast the market drops it could happen in a hurry -- in order to gain scale and be able to compete with the likes ofVanguard. The industry could well likely resemble something akin to airlines, where three to four colossal companies that make up 80 percent of market share by serving up nearly everything and competing on fees while smaller shops that provide specialized funds and services fight over the remaining 20 percent.

This scenario may seem outrageous now, but it is simply where the organic growth in money flows is heading. In most any other industry, such as retail, this would all be obvious, but the asset management business is different thanks to the double-edged sword variable of market returns, which, if good enough, can make everything seem fine.

And so long as the market never goes down again, it will be.

To contact the author of this story: Eric Balchunas at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at [email protected]