Sponsored by NASDAQ

By Andy Hyer, Sr. Analyst, Dorsey, Wright & Associates, a Nasdaq company

Nasdaq Dorsey Wright offers investors a free demo of the DWA Research Platform, which provides turnkey research and analysis for stock selection, portfolio management, and asset allocation. Click here for your customized free demo. For questions about the DWA strategies, contact us here.

Which do you trust: hard data, or professional insight? It’s an age-old debate. And yet few advisors seem to take a firm stance on the topic. It’s no wonder. After all, a large part of why clients value their advisors—and are willing to pay good money for their advice and guidance—is because they offer a high level of expertise. And if the client perceives that knowledge to be rooted in years of experience, a winning process, uncanny market intuition, or even magic, few advisors are willing to stand up and willingly burst that bubble. Especially in an environment where robo-advisors are seen as every advisor’s looming adversary. If quantitative data can do the job your clients are paying you to do, what value can you add in the end?

It’s a tough argument. At the same time, decades of historical data make it clear that a quantitative investing approach can have a substantial positive impact on outcomes, outperforming the major indices over the long term, and offering important strategic advantages in the short term. The battle of man vs. machine may never fully end, but for advisors seeking to bring the highest possible value to each client relationship, taking a quantitative approach may very well be today’s key to success.

Before we go any further, it’s important to look at how man and machine differ in their approach to making investment decisions.

Man: The traditional, qualitative approach

Traditionally, investing has been seen as more of an art than a science. The most common approach is qualitative, using highly subjective, qualitative methods to determine when and where to invest. However, that doesn’t mean the decision-making process is based purely on intuition. In most cases, advisors leverage a variety of important inputs to drive their actions, including market analysis, expert opinions, and often a healthy amount of debate as their primary tools. This qualitative approach introduces two critical challenges.

First, this scene may sound all too familiar: The investment team holds its weekly meeting to discuss new research, findings, and ideas. The discussion unfolds, and decisions are made regarding the best path forward in light of this new information. But what if the smartest person in the room is a junior advisor who is too scared to speak up? She may see a trend someone else misses, or understand a complex strategy that may help improve critical returns, but her voice may be silenced by rank, personality, or politics. Her contribution is lost, and the portfolio is what suffers.

The second challenge is that even when hard data is applied to the investing process, it is typically used as a screen—not a determining factor. The team may use data to glean insights, develop hypotheses, or back up certain theories, but in a qualitative environment, data is not the driving force behind each decision. Every decision is subjective, which makes it very easy to react to economic, political, and market shifts, even if the decision maker—the portfolio manager, financial advisor, or individual investor—is conscious that these actions are based on his or her reactions to external events.

This reality has led to the rise of a whole new field of study called behavioral finance. Behavioral finance combines behavioral and cognitive psychological theory with conventional economics and finance to better understand how and why we make irrational financial decisions. Although humans inherently strive to maximize wealth through rational decision-making, behavioral finance recognizes the fact that, perhaps more often than not, emotion and psychology cause us to behave in unpredictable or irrational ways that can lead to the irrational decisions that drive poor outcomes. This research has led to a multitude of new theories and methodologies to help remove emotion from the investment process. But is that even possible?

Machine: The systematic, quantitative approach

Advisors have been struggling with these challenges for decades, so it’s no wonder that advanced technology is now being used to help remove emotion from the investment equation, using hard data to support more consistent investing behavior. Yet, despite evidence that machines really can outsmart man when it comes to building a winning portfolio, many portfolio managers are reluctant to use data as the primary driver of their investment decisions.

One book that has helped turn this tide is James O’Shaughnessy’s classic What Works on Wall Street. First released in 1996 and now in its fourth edition, the book has become the bible on the value of quantitative, numbers-driven investing. In it, the author outlines the various qualitative approaches that can be applied to investing, including Momentum and Relative Strength, Value, and Growth. He then compares the historical performance of each method over the past 80 years.

The numbers are telling. O’Shaughnessy details the results of building portfolios based on a variety of investments factors, some fundamental (like Price to Book) and others technical (like Relative Strength). The findings illustrate that the market has historically rewarded certain investment factors and historically punished others. In other words, his book (and hundreds of other academic white papers on the topic) gives valuable insight into what actually “works” when it comes to investment management.

What does work? While one factor, Momentum and Relative Strength, demonstrated distinctly compelling investment results over time, many of the quantitative factors tested demonstrated certain levels of success—if they were sustained consistently over time.

The lesson is clear: find a robust investment process and then execute, execute, execute. The more subjectively that can be removed from the process, the better.

Can traditional active management deliver?

Knowing that the vast majority of active managers continue to use a traditional, subjective approach, the question is this: Can traditional active management deliver on its promise to beat the market?

Looking at the data, it appears the answer is no. According to the most recent S&P Dow Jones SPIVA scorecard, last year 84.62% of large-cap managers, 87.89% of mid-cap managers, and 88.77% of small-cap managers underperformed the major market indices. The numbers are even worse over a rolling 10-year period, with 85.36% of large-cap managers, 91.27% of mid-cap managers, and 90.75% of small-cap managers failing to outperform on a relative basis. That’s a problem when investors are willing to pay investment managers quite a bit of money with the singular goal of beating the market. Investors rely on the skills and expertise of investment managers to select better stocks and bonds than an index like the Dow or S&P 500.

Investors are taking note that the high fees they pay a person to manage their money often aren't yielding better results. They've yanked money from so-called active stock funds every year since 2006, according to Morningstar. Bank of America (BAC) has been tracking the performance of active managers for 14 years. And it says 2016 has been the most difficult year on record for active managers. Just how tough? Only 18% of large-cap managers outperformed the Russell 1000 Index through June 30, 2016.

While that data is certainly unfortunate, the upside is that there was a percentage of active managers who did, in fact, outperform the indices. And of the pool of advisors who succeeded in beating the market, the vast majority of these are likely to be rules-based managers who are applying a systematic, quantitative investing approach to their portfolios.

The complex leap to a rules-based model

The question of Man vs. Machine is one that had been applied to nearly every industry. Perhaps one of the earliest examples is from 1968 when psychologist Lewis Goldberg analyzed responses from more than 1,000 patients who took the commonly used Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) test in an effort to use pure data to accurately to accurately diagnose a variety of mental health conditions, including whether a patient was neurotic or psychotic. (For the patients, this distinction is vital because the treatment for each disorder is very different.) MMPI uses 600 standard questions to help differentiate and diagnose the two disorders.

Using the collected MMPI data, Goldberg developed a rules-based, data-driven model that provided an accurate patient diagnosis 70% of the time. Next, Goldberg gave the same MMPI scores to both experienced and inexperienced clinical psychologists and asked them to diagnose the patients. What he found was that his rules-based method delivered an accurate patient diagnosis more often than the psychologists, whose accuracy ranged from 55-67% (Source: Dresdner Kleinwort).

Knowing that his model was providing superior results, Goldberg ran the test again. This time he provided the psychologists with added insight: he gave them the model’s predictions for each patient. Interestingly, although the psychologists’ performance rates improved, their accuracy rate remained lower than the accuracy rate of the model. It seems the overconfidence of the doctors created a behavioral barrier to success, inhibiting their success—just as emotion and psychology have been shown to inhibit the success of investors.

Clearly, it is difficult for us humans (experienced psychologists and investment managers alike) to accept the idea that mere data can do a better, more accurate job than our well-educated, well-heeled minds! Accepting the superiority of a quantitative model demands humility. But it’s a leap active managers would be wise to take. Investors are more aware than ever of the need for alpha, and if that goal isn’t being met, it’s unlikely they’ll continue to pay high fees just for the potential. The best next step is to accept the advantages a quantitative approach has to offer, and then put that approach to work to support your own success.

Knowing the results of James O’Shaughnessy’s research, it’s logical to assume that the most promising path toward that success is to develop a rules-based model for your investment methodology, and to base that model on proven return factors. Considering that the research also showed Momentum and Relative Strength to demonstrate the greatest rate of long-term success, it seems the obvious choice.

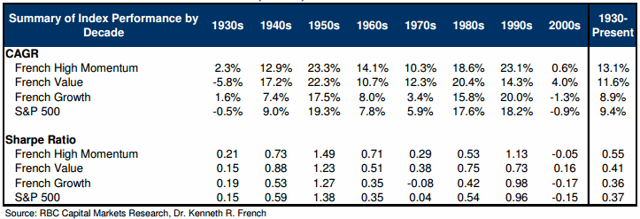

Of course, no wise advisor would make that leap without posing one key question: How consistent are Momentum returns? The answer can be found in a recent white paper published by RBC Capital Markets. As you can see in the following table, according to the research by Dr. Kenneth R. French, Momentum outperformed the S&P 500 in every decade since the 1930s.

Clearly, the margin of outperformance was larger in some decades than others, but while both Value and Growth experienced decades of underperformance, Momentum outperformed in every single decade.1

As hard as it may be for our egos to accept the superiority of quantitative data, suddenly making that leap is much easier when the numbers support the rationale for a strategy that uses Momentum and Relative Strength rather than a qualitative strategy that’s been proven to falter due to the very real impact of emotions and psychology. Suddenly the question isn’t whether a quantitative method can be trusted but, instead, can you?

Applying Momentum and Relative Strength in the real world

Momentum and relative strength have become an increasingly important part of our investment process over the years here at Dorsey Wright. In 2005, we introduced our family of Systematic Relative Strength Portfolios, a move that transformed our approach to investing. This family of separately managed accounts was based on our years of extensive testing to identify the most effective way to build and execute a Relative Strength strategy.

John Lewis, who joined Dorsey Wright’s portfolio management team in 2002, played a critical role in this process. Not only did he bring extensive experience and market insight to the team, but also his computer programming background delivered unforeseen benefits, providing tools and techniques that allowed us to take our research to a whole new level. The result was an investment process that largely stripped subjectivity out of the equation.

Now, over a decade later, we can look back and see how our Systematic Relative Strength Portfolios have performed over time. The portfolio family now includes seven distinct strategies: several focus on U.S. equities, with the others, focused on international equities, global tactical allocation strategy, and tactical fixed income. The investment universes and model constraints differ by strategy, but all seven portfolios are rules-based models using Momentum and Relative Strength.

Like any winning investment strategy, ours have gone through strong periods, as well as periods of underperformance. That said, we believe that by applying Momentum and Relative Strength in the real world, we are now in a very select group of investment managers who are able to deliver results of which we are consistently very proud. We chose a systematic strategy over a subjective strategy, and the results speak for themselves.

Conclusion

The goal of every active manager is to outperform the benchmarks and deliver the highest possible value to your clients. Research and data show that in the battle of Man vs. Machine, a systematic, rules-based approach is the clear winner and that a quantitative strategy is the most reliable path to achieving this goal. While there are multiple, systematic methods available, eighty years of data show that Momentum and Relative Strength are among the very best.

It can be a difficult leap of faith to step away from a traditional, subjective approach, but not only has behavioral finance research shown that emotions and psychology often cause us to make poor decisions, but data also shows that deviating from your game plan is the biggest drag on performance over time. The answer is to create a systematic, data-driven process that specifically leverages the power of Momentum and Relative Strength—and to stick to that process, regardless of market conditions.

1The performance numbers here are based on price returns, not inclusive of dividends or transaction costs. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The potential for profits is accompanied by the possibility of loss.

Past performance, hypothetical or actual, does not guarantee future results. In all securities trading there is a potential for loss as well as profit. It should not be assumed that recommendations made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance as shown. Investors should have long-term financial objectives. Advice from a financial professional is strongly advised.

Dorsey, Wright & Associates, LLC, a Nasdaq Company, is a registered investment advisory firm. Neither the information within this article, nor any opinion expressed shall constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation or an offer to buy any securities, commodities, or exchange traded products. This article does not purport to be complete description of the securities or commodities, markets or developments to which reference is made.