By Melissa Mittelman, Sabrina Willmer and Dakin Campbell

(Bloomberg) --Goldman Sachs. BlackRock. Blackstone.

They move markets, influence governments and directly employ tens of thousands of people — indirectly, many more. They’ve had their hands in everything from providing insurance in New Zealand to helping take social-media company Snap Inc. public to managing the money you’re relying on for retirement.

These three bellwethers of their respective corners of finance — investment banking, traditional asset management and alternatives — offer insight into the forces that will shape the investing landscape in the decade to come. Whether or not they’ll remain the titans they are today depends on their ability to own the challenges ahead.

Each one looks at the years to come from a different vantage point, with hurdles and opportunities on the horizon.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc., whose original profit drivers are restrained by regulations and damped demand, is eyeing asset-gathering businesses like investment management and digital banking. While it’s struggled to convince public shareholders of its worth, Blackstone Group LP is benefiting from growing appetite for alternatives and is reaching for retail investors and ultimately retirement plans — a space dominated by firms such as BlackRock Inc. And BlackRock, vulnerable to a cost-cutting war on passive funds that account for a large chuck of its revenue, is expanding its alternatives business and pivoting to be more of a data and service provider.

The chance for these companies to stay dominant depends on their ability to fit into the investor playbook. Investors today are starved for yield in many asset classes and don’t want to pay up for products without premium returns. That’s created a barbelling of portfolios, with high-yielding alternatives they’re willing to pay for on one end and passive, market-tracking products they want cheaply on the other.

Blackstone, BlackRock and Goldman Sachs solve needs at different parts along the spectrum.

The world’s biggest alternative-asset manager, Blackstone is raking in money as investors including endowments, sovereign wealth funds and pension plans pour near-record sums into alternatives to offset anemic returns they’re getting elsewhere.

“Our business model is to invest in things that people can’t buy and sell in liquid markets,” Blackstone President Tony James said in an interview. “It’s more labor-intensive, it requires specific expertise and you have to take illiquidity. But in return, you get much higher returns.”

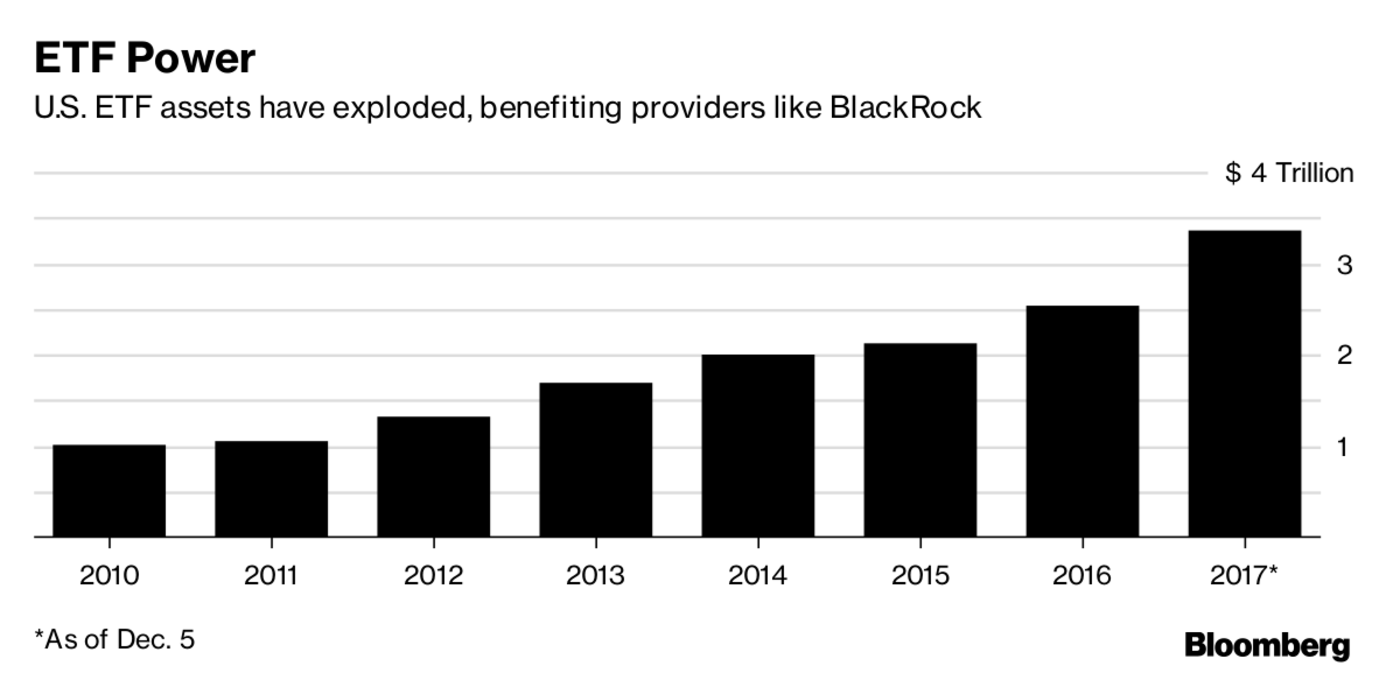

At the other end of the barbell, BlackRock, as the world’s largest traditional asset manager and biggest provider of exchange-traded funds, has benefited from demand for low-cost offerings. The company’s ETFs saw a record $138.2 billion of net inflows in the first half of the year, and BlackRock managed $3.9 trillion in passive strategies at the end of September.

BlackRock thinks the role it should play is much broader than just providing products across every asset class. It’s focused on tailoring portfolios around specific needs of individual clients and using technology to deliver those offerings, President Rob Kapito said in an interview. A barbell approach is too simplistic because an investor can lose money on both sides, he said.

“BlackRock wants to be the driver of the ecosystem when it comes to investing,” said Kapito.

True to its role as a middle man, Goldman Sachs, once the most profitable securities firm in Wall Street history, has positioned itself on both sides. The firm manages private equity, infrastructure and other illiquid strategies targeted at wealthy clients and institutions, as well as a suite of ETFs it sells to retail investors. The ETF business, while small compared with the likes of BlackRock and Vanguard Group, has nonetheless attracted money at a torrid pace. Many of its early offerings cost mere basis points, putting added pressure on competitors.

Goldman Sachs Chief Executive Officer Lloyd Blankfein is counting on new areas of growth as he adjusts to a phalanx of post-crisis regulations. A ban on using the firm’s own money to trade and limits on how much capital can be invested alongside fund clients have curtailed some of the company’s fattest profits. Higher capital requirements have handcuffed returns. And while President Donald Trump’s administration is in the midst of reviewing post-crisis rule changes and may loosen some regulations, few expect a return to the Wild West.

Making matters worse, low volatility and rising markets have sapped demand for the sophisticated advice and market savvy that have long been Goldman Sachs’s calling card. That means the pivot to retail banking and investment management may be the key to the company’s future success.

“We’re right to focus on whether, in the moment or in the foreseeable future, we are building a set of businesses that play through a cycle,” Stephen Scherr, the head of Goldman Sachs’s consumer and commercial banking division and the company’s former chief strategy officer, said in an interview. “We won’t look at one quarter or one month or one week and render some judgment. We’ll come at these with a conservative bias and look to build them to stand the test of time.”

As investors demand lower fees for ETFs and cutthroat competitors such as Vanguard continue to slash prices, BlackRock could be hard-pressed to make money in a business in which it’s gained market share.

“At some point the growth slows,” said Kyle Sanders, an analyst at Edward Jones & Co. “The pricing is never going to get better.”

The firm is betting on scale to offset the decline in margins. The wager has paid off so far: BlackRock said it earned back the revenue loss from cutting prices on its ETFs for buy-and-hold investors less than a year after the reduction.

The large bet on passive investing could backfire if active strategies make a comeback. Passive strategies, including ETFs and index offerings, accounted for 65 percent of BlackRock’s assets under management and 41 percent of revenue at the end of the third quarter.

“The biggest impediment would be if people are wrong about the passive versus active shift,” said Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Alison Williams.

Kapito said that even if the passive trend reverses, BlackRock has a suite of active offerings that can capture those flows.

The secular disappearance of public companies is also weighing on the future of firms like BlackRock. A dwindling in the number of public companies that’s occurred in the U.S. over the past two decades not only limits the investable universe for passive products but also lessens their value as a proxy for economic growth.

A gradual de-listing of stocks “means more and more that the players of the game in the financial markets will be private equity investors like Blackstone,” said Massimo Massa, a professor of finance at Insead.

For Blackstone, anything that threatens its ability to generate investment outperformance threatens its growth. Rising returns in other asset classes, regulatory restrictions on leverage, increased competition from sector-focused funds or the challenge of putting money to work in today’s high-priced environment could all be limiting factors. And when it comes to its public shareholders, the firm has had a tough time convincing them of its value — its stock price hovers near the value it listed at back in 2007.

The private equity industry overall is also in the midst of succession planning, with many of Blackstone’s peers naming their next generation of leaders. While the firm has a deep bench of candidates, the question lingers among investors eager to know who will succeed CEO Steve Schwarzman.

Blackstone also has set its sights on a challenging new pool of potential clients: ordinary savers. Schwarzman has said that accessing such non-accredited investors is one of the firm’s “dreams.” But offering private equity to individuals has been a challenge because the investments are hard to convert to cash quickly and carry higher fees than those of traditional mutual funds that populate 401(k)s.

BlackRock is working to manage its challenges. For years, it’s tried to improve its stock-picking arm, which has lagged behind peers and suffered outflows. Earlier this year, it fired more than 30 people in the business, moved billions of dollars into cheaper offerings where quants play a role and is building actively managed equity strategies fueled by robots.

The asset manager is also expanding its alternatives business. Overseeing $131 billion, the alternatives unit is currently a small part of overall assets and revenue, but could be a growth driver in years to come.

Goldman Sachs, which converted to a bank during the financial crisis to access government rescue funds, has been amassing retail deposits that it’s using to support a new online lender named Marcus. Taken together, Marcus, a private wealth business and other asset-management efforts will account for 50 percent of the firm’s revenue growth in three years, according to a plan laid out in September by Co-President Harvey Schwartz.

Blackstone has steadily been diversifying its client base and areas of investment. The firm is tapping retail investors, attracting big checks from sovereign wealth funds and chasing longer-term lockups on money — all in the pursuit of varied and enduring sources of capital. It’s also pushing beyond its core areas of private equity, real estate and credit by pursuing infrastructure and expanding tactical opportunities, a catch-all group that’s invested in things as disparate as Brazilian data centers and insurance products.

The three firms are rushing to stay ahead of a data-driven, millennial-backed onslaught that’s forcing the investment landscape to evolve. Consumers have more choice. Automation is making scale less relevant. Data is becoming more valuable.

BlackRock, which has been built on scale and relies heavily on passive products, is working to remain ahead of technology disruption. To do so, it’s pivoting to become more of a data and service provider, an attempt to create a steadier revenue stream and push more money into its offerings.

CEO Larry Fink has said he wants technology to drive 30 percent of BlackRock’s revenue in the next five years. The asset manager is relying on its risk management system, known as Aladdin, to help push it toward that goal. BlackRock has sold the software, originally used by its portfolio managers, to institutions and more recently to wealth managers.

Goldman Sachs, too, has used technology to get closer to clients. Its Marquee platform provides access to cutting-edge risk management tools and makes it easier to deliver custom products such as structured notes for retail investors. Marcus caters to borrowers with a consumer-friendly website. And last year it purchased Honest Dollar, which offers retirement plans for workers, including many millennials, employed in the so-called gig economy.

“For me, it’s less about whether intermediaries of capital will remain relevant — they will be — but I think the issue is just how they go about their craft,” Goldman Sachs’s Scherr said. “Whether you are relevant as an intermediary of capital is really the question. Are you still matching those who have it and those who need it? And are you doing it in a way that perhaps makes more elegant use of technology than others?”

Blackstone’s business relies less on broad-based market movements and more on the ability of its hundreds of dealmakers to execute on many individual investments. While that exposes the firm to departures of top performers and keeps Blackstone in a constant war for talent, the risk of instant replication by a new entrant to the industry is lower.

“You have passive, which is pure machine; you have active, which is picking stocks and bonds but with no real influence over the company; and then you have us, the interventionists, where we change the asset,” said Joan Solotar, head of private wealth solutions at Blackstone. “That’s not a machine-based process.”

Peter Grauer, chairman of Bloomberg LP, is a non-executive director at Blackstone.

While the successes of three financial titans — Goldman Sachs, BlackRock and Blackstone — have so far been built on mastery of their own areas, their ongoing leadership may depend in part on their abilities to tap into each other’s magic.

“At the end of the day, each will retain their flavor but they’re going after the same thing: attracting the next client or dollar and scaling from there,” said Paul Schaye, the managing partner of Chestnut Hill Partners, which helps investment firms evaluate transactions. “If they don’t get bigger, they’ll get passed over.”

To contact the authors of this story: Melissa Mittelman in Boston at [email protected] Sabrina Willmer in Boston at [email protected] Dakin Campbell in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Devin Banerjee at [email protected] Elizabeth Fournier