Well it’s only $12 billion, a “rounding error” as sarcastically teased in a WAll Street Journal opinion piece.

Indeed, in the context of the recent deficit, exploding tax breaks and other spending, $12 billion in aid to farmers is chump change (Trump change?). However, it’s the symbol that’s important—to say nothing of the precedent, i.e., helping businesses that will be hurt by tariffs and where the money will come from.

The short answer is that money will come from the Commodity Credit Corporation, an entity from The Great Depression, designed to support farm prices by buying surpluses. If said surpluses aren’t sold, the taxpayer is on the hook, meaning more deficit. Of course, it’s the precedent to consider, which is simply that such aid might have to go to other areas as the trade war mounts. This surely is obvious.

To wit, we have the following quotes to note: from Bob Corker, “You have a terrible policy that sends farmers to the poorhouse and then you put them on welfare,” while from Patrick Toomey, “The (USDA) is trying to put a band-aid on a self-inflicted wound,” and from PresidentTrump, “Tariffs are the greatest!”

I came across a 1996 Average Earnings Index report, Three Simple Principles of Trade Policy, by Douglas Irwin (relayed to me by Paul Kasriel of The Econtrarian). It’s a long 30-page monograph, but eminently readable, and I can’t imagine a more cogent explanation of the risks connected to tariffs than this. I’ll merely highlight Irwin’s three principles and some of his views. First principle: “A tax on imports is a tax on exports” and that the converse is true, that when a country seeks policies to expand exports it also will add to imports. This is the concept of “equivalency.” At a basic level he explains that if countries are held back from selling to the U.S., they won’t earn money to import from the U.S. Flipping sides of the same coin is how Irwin explains it. Simple, right? He was prescient when he wrote: “Because the economic equivalency of export and import taxation is not intuitive, clearly they are unlikely to be considered equivalent in the political arena.”

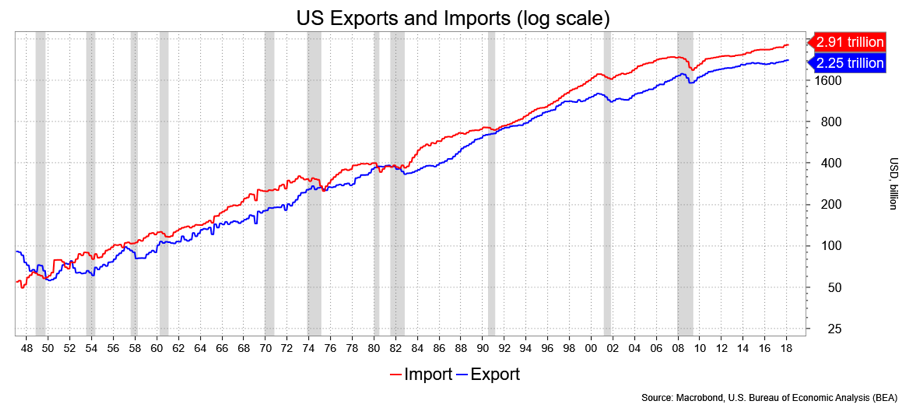

An interesting aspect that he brings up is that a tax that reduces exports (say retaliation) will compel the domestic manufacturer to work on replacing imports, thereby further weakening the export side, i.e., prompt a move towards import-competing goods. Below is a chart I tried to come up with to demonstrate his view to symmetry regarding the export/import connection, or its equivalent.

Irwin’s second principle is that “Businesses are consumers too.” He starts with Adam Smith’s attack on mercantilism as a detriment to the consumer (via higher costs that only benefit the producers), touches on the Corn Laws and then moves to the trade angle and the consumer cost argument. Again, he anticipates the current realm by commenting, “jobs are viewed as being much more important than consumer welfare in the political arena. If the question comes down to saving a few hundred jobs in some industry or saving consumers a few hundred dollars in income, the policy of import protection will win every time.”

As it turns out, businesses are bigger consumers of imports than households. It was true at that time and remains true today. Thus, import protection will cost jobs, albeit in other businesses which he suggests provides a politically sound and strong argument against protection.

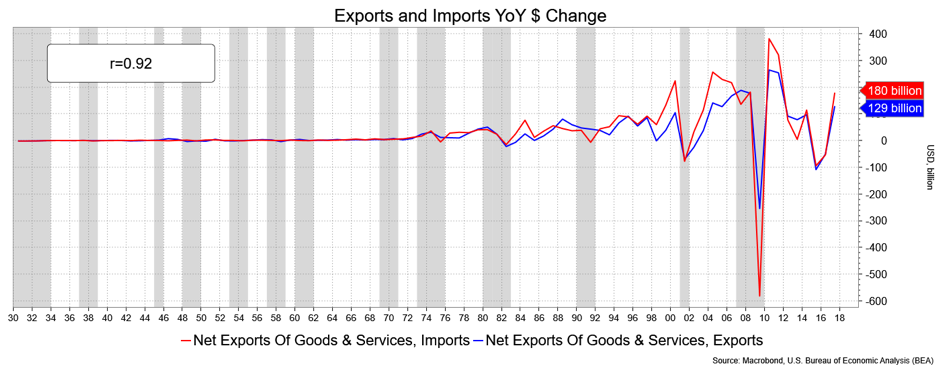

This chart above shows the year-over-year change that replicates the one Kasriel used. The idea is that if import barriers raise the price of imported things, the demand will fall. So, the foreign currency’s value will fall as well, relative to the dollar reducing further the competitiveness of the U.S. exports. Irwin wrote about this using the yen as an example and Kasriel wrote about it in reference to the yuan. The outcomes are the same; tariffs will cause the dollar to strengthen and so reduce the resulting more expensive exports.

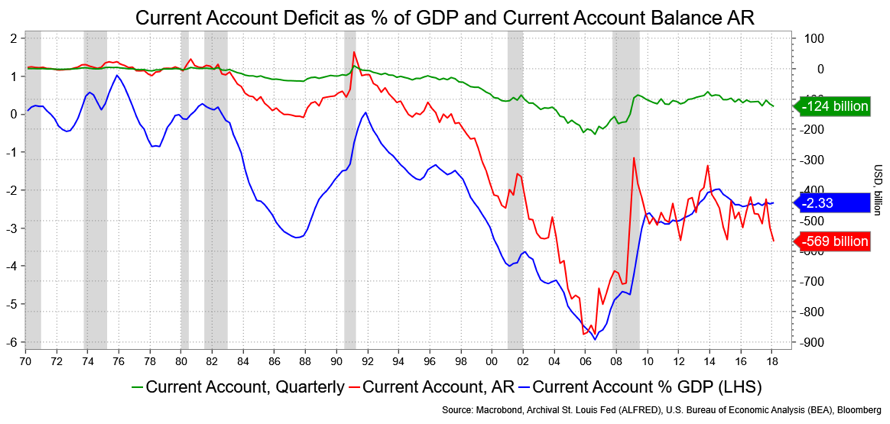

Finally, Irwin’s third principle says “Trade imbalances reflect capital flows.” And do I love this, “... this lesson is still apparently lost on many policy officials today, as when one hears that the United States suffers a trade deficit because its market is more open than those of other countries, or that Japan has a trade surplus because its market is closed to imports.” Substitute China for Japan and you have an update of the message.

As Irwin states, balance of payments discussions make for a very dry conversation, but is important to the trade deficit story but he makes it clear enough; “if a country is buying more goods and services from the rest of the world than it is selling, the country must also be selling more assets to the rest of the world than it is buying.”

And this is precisely what we’re doing. Exports minus import = savings minus investment, he reminds us. If we have a negative on the left side of the equation, we’ll get a negative on the right side. If we have a trade deficit, we’ll need external investment. Further, “A government's borrowing to cover a fiscal deficit can be one of the largest drains on a country's savings and can therefore lead to a current account deficit.”

His solution is that if a country wishes to reduce its trade deficit, it needs to reverse capital flows (increase savings) by reducing the fiscal deficit. And how’s that looking?

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.