The New York Times recently offered an Op-Ed piece that takes aim at President Donald Trump to a degree, as well as the GOP, for trumping (pun intended) up the unemployment rate while de-emphasizing the wage story.

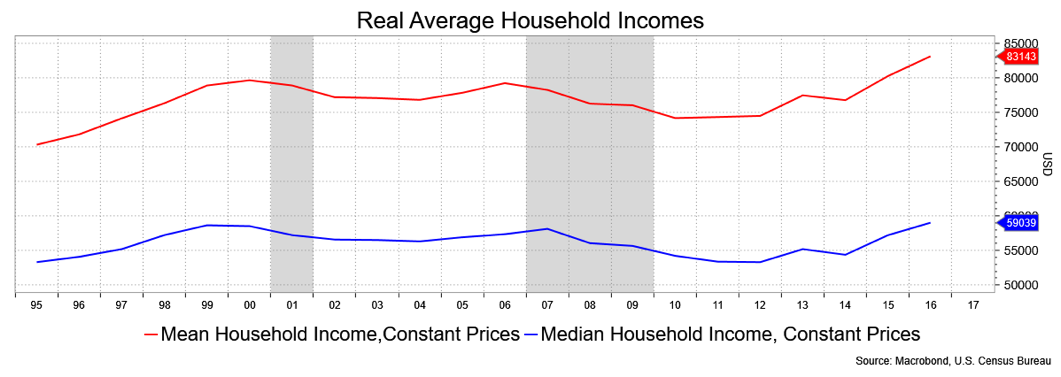

The partial blame they lay on Trump is his aggravation of the oil story (Iran sanctions), even as they mention “events” in the Middle East, Russia and Venezuela as an angle to higher oil. I’m hardly one to avoid casting stones at many, if not most, of Trump’s economic policies, but this one is hard to swallow—low household income gains have been with us for at least 20 years and have been skewed to higher earners (median versus mean incomes show that) for most of the Obama years. Sorry David Leonhardt, but it’s not a Trump slump.

It is, however, an ongoing problem, and I don’t see any reason to think that real wages are about to accelerate when buybacks are a more active use of cash then, say, investment for productivity gains.

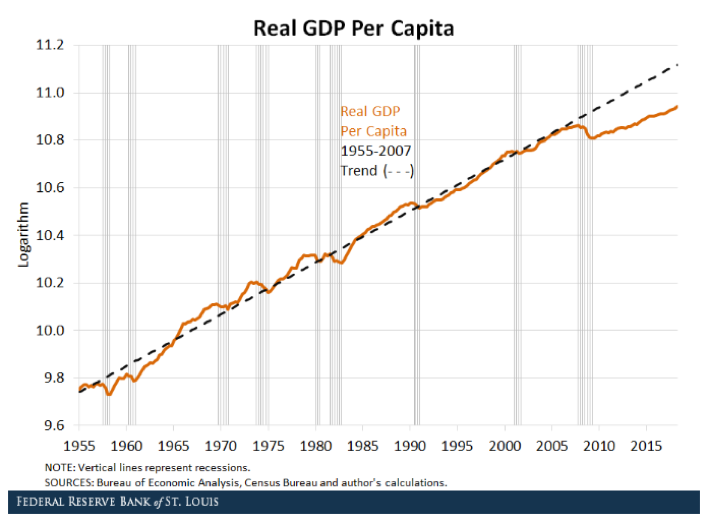

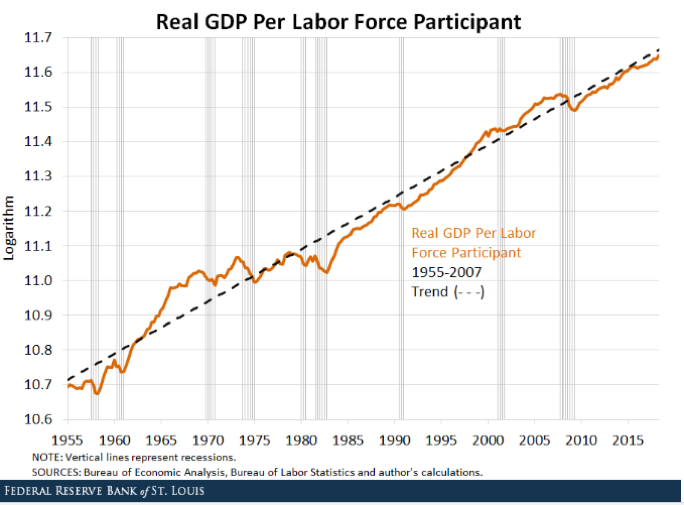

Cue the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which offers an interesting take on GDP and why it’s been slow in a recent piece on “GDP, Labor Force Participation and Economic Growth.” They acknowledge that relative to trend GDP has been slower in this cycle, fodder for politicians and the blame game. Before the Great Recession, GDP grew at a 2.2 percent average rate per capita but has since eased back to 1.6 percent.

At least part of the story is the drop in labor force participation. GDP growth requires both productivity gains and more workers: alas, both have been very slow. The second chart shows GDP per Labor Force Participant historically and against the trend. Here, there’s no disparity at all: the recovery since the recession is in line with the trend with average growth rate both at 1.7 percent. The St. Louis Fed’s logical conclusion is that: “When accounting for demographic realities (specifically, their impact on the labor force), the U.S. economy has displayed a satisfactory performance and a healthy outlook since the end of the Great Recession.”

Any caveats? One big one warrants attention. Productivity has been in slo-mo since 2000 and is the second input to better GDP growth demands. Government policies could encourage more workforce growth—through immigration, for example—but whether they encourage productivity enhancing technology advances it is, as the authors say, an open question.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.