Investors navigate the oft confusing financial markets by relying upon their preferences. In no other investment is preference more exquisitely expressed than in preferred stock. Holders of preferred shares have priority over common shareholders with respect to dividend payments and claims to corporate assets upon liquidation. Preferred shares, known as “hybrid securities,” occupy a grey area in a company’s capital structure, with features of both equity and debt.

Because of their (generally) fixed dividend payments, preferred shares appeal to income investors, especially those in higher tax brackets. Dividends paid to preferred shareholders are higher than those earned on common stock and exceed, too, the interest received from many bonds. Like common stock, preferred shares can gain value if the issuing company fares well but can be highly sensitive to changes in interest rates.

The trouble with preferred shares is that it’s not easy to build a portfolio position with them. For one thing, not every company issues preferred stock. For those companies that do, the array of preferred equity offered—with their qualifications on dividends, convertibility and redemptions—can be bewildering. The market for preferred shares, too, is notoriously thin.

Enter preferred-stock exchange-traded funds (ETFs). On the scene for more than a decade, preferred ETFs offer immediate diversification and liquidity in just one trade. Most are plain vanilla funds that track an index±either broad or narrow in scope.

For most investors, an allocation to preferred shares properly comes from the fixed income side of their portfolios. Preferred equity is typically used as a diversifier, though many retirement-minded investors tend to think of it as a core allocation.

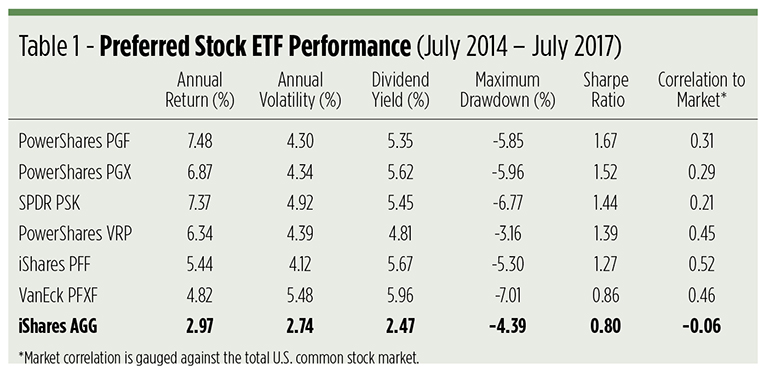

A half-dozen “seasoned” preferred-equity ETFs concentrate on the U.S. market. By “seasoned” we mean those with track records at least three years long. All provide dividend yields exceeding that of the Barclays Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF (NYSE Arca: AGG) and, in spite of their higher volatility, offer better risk-adjusted returns than the bond benchmark.

The iShares U.S. Preferred Stock ETF (Nasdaq: PFF), with its $18.6 billion asset base, is the largest ETF in the table. The 286-issue portfolio is heavily populated, like most preferred-equity ETFs, with financial securities. In fact, nearly three-quarters of the portfolio’s given over to financials. Real estate securities weigh in at 10 percent while six other sectors each contribute two to three percent to the portfolio. Credit quality isn’t a consideration in the fund’s index methodology, though exposure to any single issuer is capped at 10 percent. The fund’s holding cost is currently 47 basis points (0.47 percent).

The $5.3 billion PowerShares Preferred Portfolio (NYSE Arca: PGX) targets both investment-grade and high-yield preferred securities. The majority of PGX’s 257 holdings are, in fact, rated BBB or better. Like PFF, financial issues—mostly of money-center banks—dominate the portfolio, followed by securities of real estate firms. The fund’s annual expense ratio is 50 basis points.

A relatively young sibling fund, the PowerShares Variable Rate Preferred Portfolio (NYSE Arca: VRP), holds variable and floating-rate preferred shares. Payouts on floating-rate shares are driven by a benchmark reference rate to which a fixed spread, or risk premium, is added. Variable-rate preferreds pay fixed dividends for a time after issue before converting to a floating-rate scheme. Again, the vast majority—75 percent—of the 117 issues held by VRP are financials. Utilities are secondmost at 14 percent. You’ll pay 50 basis points to hold this $1.8 billion ETF for a year.

Rounding out the Invesco lineup is the $1.7 billion PowerShares Financial Preferred Portfolio (NYSE Arca: PGF), which does away with the pretense of sector diversification. This fund’s 93-issue portfolio is heavily weighted toward money-center banks. Investors should be keenly aware of PGF’s inherent concentration risk. The fund’s index methodology caps exposure to a single issue or issuer at 20 percent. Preferred shares of Wells Fargo & Co. (NYSE: WFC), in 10 different issues, account for nearly 14 percent of PGF’s heft, while a single HSBC Holdings plc (NYSE: HSBC) issue takes up 7 percent. With 58 percent of its holdings rated BBB or better, PGF skews toward investment-grade exposure. All this comes at a fairly steep price: the fund’s annual expense is 63 basis points.

If concentration risk scares you, the SPDR Wells Fargo Preferred Stock ETF (NYSE Arca: PSK) might offer more reassurance. This $560 million portfolio targets investment-grade nonconvertible preferreds and functional equivalents. Exposure to any one of the fund’s 153 issues or any single issuer is capped at 5 percent. PSK’s tilt toward financials—at 67 percent of its portfolio weight—is lighter than most of its tablemates. Lighter, too, is the fund’s annual expense charge of 45 basis points.

For those investors who’d like to eschew the financial sector entirely, there’s the VanEck Vectors Preferred Securities ex Financials ETF (NYSE Arca: PFXF). While the $473 million PXFX portfolio excludes financials, it does take in real estate securities. REIT preferred shares make up about a quarter of the 111-issue PFXF portfolio, about equal to its electric-utility allocation. You get more volatility with PFXF, but at 41 basis points, it’s the least costly ETF in the table.

The best and the worst

Over the past three years, the presence of financial company shares has been the principal determinant of returns earned by preferred-stock portfolios. At one extreme is PGF, which is composed solely of financial issues; at the other is PFXF, which avoids them entirely. PGF has earned the highest risk-adjusted return, reflected in its 1.67 Sharpe ratio; PFXF is in the cellar with a 0.86 ratio.

Risks and rewards

Financial stocks, namely those of banks, are inherently risky assets. During the 2008–09 recession, most preferred-share dividend suspensions came from financial firms. On the other hand, there were no dividend suspensions on utility preferreds during the economic swoon.

It’s more than just dividends at risk, though. The recession was brought about by a meltdown in the financial sector. The impact was felt keenly by preferred-stock ETFs. The iShares PFF portfolio, for instance, was drawn down 56 percent between July 2007 and February 2009. The contemporaneous selloff for the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (NYSE Arca: SPY) was 51 percent. Still, it took until March 2012 for SPY to recover; PFF bounced back more quickly and was out of the hole by July 2010.

Preferred shares are not well correlated with common equity or bonds, so they can be effectively used to diversify a portfolio. But, given the skew toward financial firms found in most preferred-equity ETFs, zealous investors could easily find themselves overexposed to this volatile sector. Most preferred-stock ETFs should therefore be used as a seasoning rather than an entrée.

There’s a more generic risk in holding preferred equity: calls. Like some bonds, certain preferred shares can be redeemed by the issuer. The call feature allows a company to buy back the shares at par after a certain time passes. The likelihood of a redemption spikes when interest rates decline as issuers look to take high-coupon issues off their books and replace them with new issues at a lower yield. So, even though lower interest rates ordinarily have a positive effect on preferred-share prices, ETF shareholders may see their dividend payouts reduced if interest rates decline significantly. With that in mind, it pays to look at an ETF’s holdings to determine the extent of this risk before making an investment.

Of course, holders of floating and variable-rate preferred ETFs may actually benefit from future interest rate hikes.

In this low-yield environment, the dividends offered by preferred-stock ETFs are certainly attractive. The modest volatility of these funds, too, is appealing to risk-averse investors. For those seeking the highest returns from preferred-equity ETFs, though, they’ll need to feel sanguine about the financial sector’s prospects. They’ll also need to look under the hood of each fund to determine the likelihood of keeping their dividends.

We’d all prefer high dividends to low payouts, and low volatility to excessive variance. Preferred-stock ETFs offer us the opportunity to play to our preferences.

Brad Zigler is WealthManagement's Alternative Investments Editor. Previously, he was the head of Marketing, Research and Education for the Pacific Exchange's (now NYSE Arca) option market and the iShares complex of exchange-traded funds.