By Rachel Evans and Annie Massa

(Bloomberg) --A hidden war is taking place within your exchange-traded fund, and some of the biggest names on Wall Street are losing out.

Banks like Goldman Sachs Group Inc. have surrendered a once-lucrative type of market making amid an onslaught of regulation that’s wiped out profit margins. Nimbler firms -- so-called high-frequency traders -- have picked up the slack.

These speedsters have harnessed technology to gain an edge over banks as the U.S. ETF market surpasses $3 trillion in assets and trading explodes. That shift, though barely perceptible to the outside world, has made it easier and cheaper for everyone from mom and pop to the world’s biggest pension funds to buy and sell these increasingly popular products. But it’s also placed a market that’s 60 percent retail into the hands of less-regulated firms.

“Recent regulatory changes have caused many banks to re-evaluate their various lines of business, one of which was the trading and market making in ETFs,” said David Mann, head of global ETF capital markets at Franklin Templeton, and the firm’s main point of contact for market makers. “This allowed smaller firms who focus solely on providing liquidity in ETFs to gain market share.”

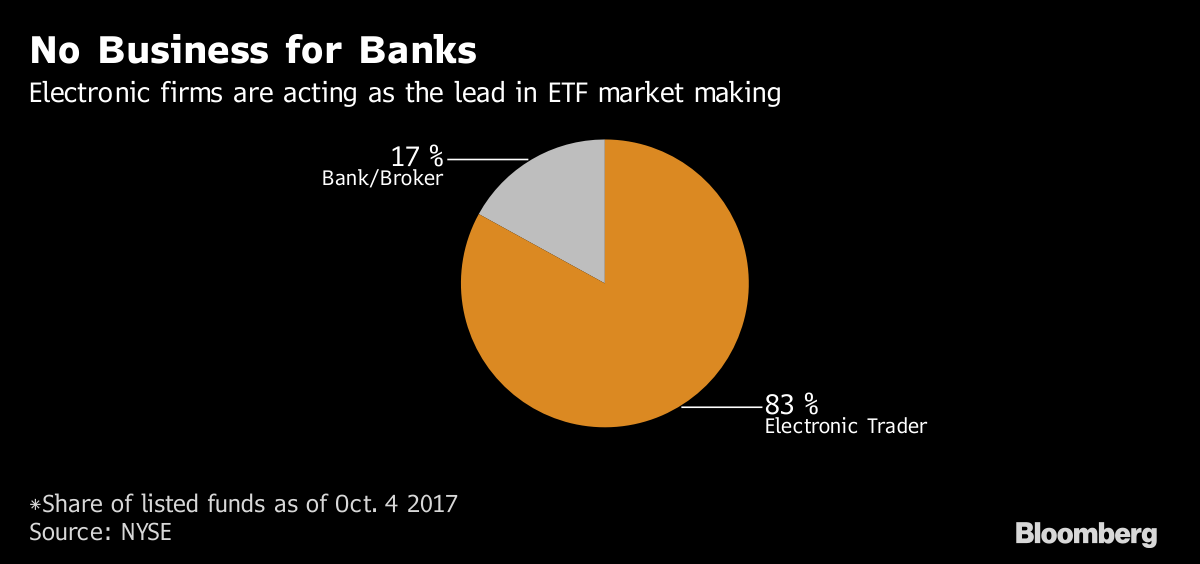

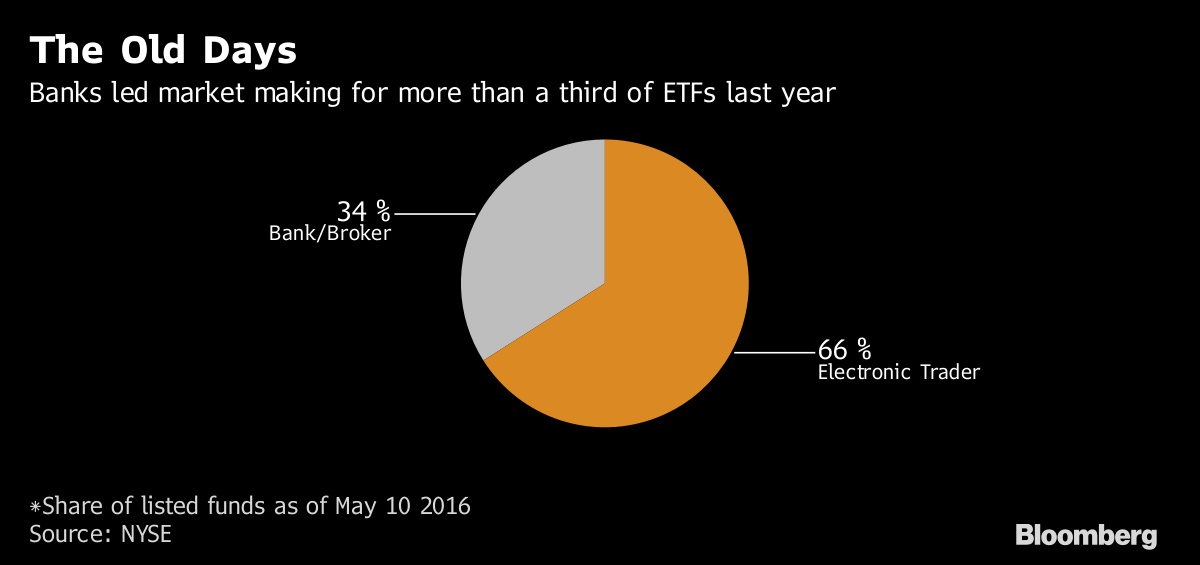

Over the last few years, high-speed traders have moved from quietly trading ETFs in the shadows, to overseeing much of the market. On NYSE Arca, which hosts the majority of U.S. ETFs, 83 percent of funds have appointed an electronic firm to the key role of lead market maker, instead of a bank or conventional broker-dealer.

Amsterdam-based IMC, for example, was the lead market maker for 125 ETFs on NYSE Arca as of Oct. 4, up from just one 17 months earlier. Other growers include Jane Street Group LLC, Flow Traders NV and Latour Trading LLC. Citadel Securities LLC is considering getting into the business.

Goldman Sachs has meanwhile backed away from this job over the last year and a half, resigning its lead role on more than 300 of the 359 NYSE-listed funds it used to assist, data from the exchange shows. Among the funds Goldman relinquished was the nearly $14 billion Guggenheim S&P 500 Equal Weight ETF, which went to IMC.

Goldman Sachs had been looking to exit the business for a while as the rewards didn’t offset the obligations, a person familiar with the matter said, asking not to be identified because the details are private. Tiffany Galvin-Cohen, a spokeswoman for Goldman Sachs, said “we remain committed to serving our clients as an active market maker in the ETF space.” Resigning as a lead does not stop a firm doing other types of market making.

Greater Constraints

Lead market makers are a fund’s linchpin, setting the price that investors pay to trade an ETF over an exchange. LMMs are required to post the “ national best bid-offer” -- the most attractive price at which an investor can buy or sell that fund -- for most of the day, and receive a rebate from the ETF’s home exchange in return.

Banks used to benefit from this model as much as other firms, but the financial crisis changed all of that. New rules designed to ensure lenders have a buffer to weather tough times have boosted the amount of capital they must set aside to cover these trades and constrained trading desks.

Not so for the new guard. Protected from the capital burdens that plague the banks, these firms leverage lightning-fast technology and complex algorithms to do millions of trades a day. Each transaction earns firms mere cents, but do enough and it starts to pay off.

“You’re really dependent on increasing your trading volume to help manage and secure those fractions of a penny,” said Ryan Sullivan, vice president of Brown Brothers Harriman & Co.’s global ETF services. “That’s resulting in some of the shift that we’re seeing.”

Getting Harder

But that shift -- the rise of electronic traders at the expense of banks and conventional brokers -- may be set to slow. Lead market makers are usually expected to invest about $5 million of startup capital in the ETFs they support, and as the number of funds tops 2,000 in the U.S., that’s less and less sustainable.

“The concentration of firms that are providing lead market-maker services is the biggest systemic risk in the market,” said Phil Bak, chief executive of ACSI Funds and Exponential ETFs. “There are plenty of firms that could step in, but the incentives aren’t there. That’s the risk people should be looking at.”

From June 2018, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission will gather information about which firms are “creating” or “redeeming” ETFs by switching an agreed-upon bunch of securities for shares in a fund. While this role is distinct from making markets, many firms operate in both the primary and secondary markets, and the data gathered could inform future policy, according to the SEC.

That could give banks a second chance. Credit Suisse Group AG has, for example, already boosted the number of ETFs it works for over the last 18 months to “assist our strategic partners,” according to Robert Bernstone, a managing director in equities at the bank. Royal Bank of Canada’s RBC Capital Markets has also ramped up its business.

If market making becomes more of a relationship business, banks may find they have a place alongside the high-speed firms. But for now, their fast electronic counterparts have the upper hand.

“We are still growing and evolving our client offering in the ETF space, which includes evaluating whether we want to take a more active role in the LMM business,” said Cory Laing, head of ETF and one-delta institutional sales at Citadel Securities. “We’re working with a lot of sponsors to understand their needs and where they see a role for us to play in the rapidly evolving ecosystem.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Rachel Evans in New York at [email protected] ;Annie Massa in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Nick Baker at [email protected] ;Nikolaj Gammeltoft at [email protected]