By Frank Caruso

Not long ago, sportswear company Under Armour (UA) captivated investors with explosive earnings growth. But as its shares unraveled last year, UA taught investors an important lesson about the dangers of relying solely on earnings growth to identify long-term winners.

Many analysts focus on earnings as a key measure of a company’s growth prospects. Yet, earnings tell only a partial story about a company’s true economic prospects. Earnings can’t tell you how skillfully a management team deploys capital. They offer no insight into the quality of a company’s profit streams. And earnings alone can’t really identify companies that can generate long-term value for shareholders, in our view.

Fundamental returns—which are a way of looking at business profitability—are much more insightful. By putting returns on invested capital (ROIC) or return on assets (ROA) at the center of company research, we believe, investors can discover whether a company is investing intelligently to generate its profits.

What Went Wrong with Under Armour?

UA is a case in point. From the end of 2013, UA’s stock rallied as earnings advanced by 20% a year on strong sales. But many analysts missed something: a 35% annual increase in UA’s asset growth. As a result, marginal returns were diminishing and profit margins were shrinking on every incremental dollar of sales.

ROA dropped from over 16% at the end of 2013 to about 11% in 2016 (Display, left chart), while UA’s asset base doubled. Profit growth wasn’t keeping up and could not fund the company’s expanding asset base (Display, right chart). Its return on incremental capital fell well below its cost of capital at 7%. In other words, the company destroyed value by growing earnings—and making bad investments. Eventually, the market caught up and the stock price declined from late 2015.

In contrast, Nike has maintained a very high level of ROA over the past decade. The company has generated solid returns by investing in new automated manufacturing technologies that bring customized products closer to consumers. By doing so, Nike saves on shipping costs, duties, and tariffs which helps support profitability. Its stock advanced significantly over the past few years.

Cost of Capital Matters

The UA story presents a challenge to conventional wisdom on Wall Street, which suggests that investor sentiment about future earnings determines a company’s stock price. We disagree. What we think matters most is the amount of capital—financial or physical—that a firm deploys to generate its earnings. After all, any dollar management invests is a dollar shareholders could have invested for themselves. So a firm’s ROIC must exceed a certain threshold, the so-called “cost of capital,” for its stock to perform well over the long term.

Cost of capital is elusive; although it isn’t listed in a company’s reports, its influence is everywhere. For example, when a company’s shares plunge after announcing a large acquisition that’s “accretive” to EPS, investors are really reacting to an inefficient investment decision. Without a focus on cost of capital, companies seek to enhance value using all sorts of tricks—from aggressively buying back shares to rapidly growing assets. Ultimately, companies pursuing low-return/high-growth strategies like these are punished for their recklessness.

Don’t Ignore the Balance Sheet

Earnings are much more visible. But earnings growth can be driven by things that have nothing to do with a company’s business, such as a cyclical industry recovery, accounting changes or financial engineering. What’s more, earnings ignore balance sheets—which can provide vital signals on business health and long-term growth.

Here’s another way of looking at it. Consider two companies with similar earnings growth. If all else is equal, the company boosting its earnings with less capital will clearly be the better business because it will generate more free cash flow.

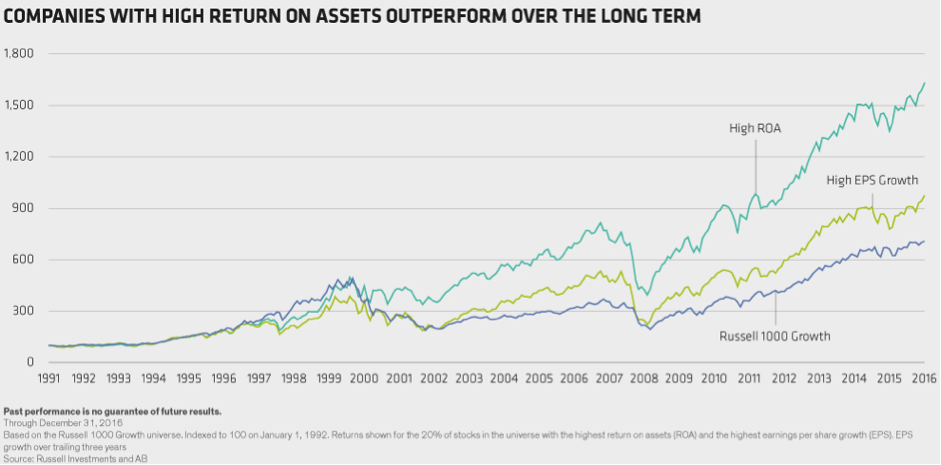

Focusing on returns can deliver clear benefits for investors, in our view. In fact, U.S. stocks with high ROA have consistently outperformed stocks with high earnings per share (EPS) growth—as well as the Russell 1000 Growth Index—over more than three decades (Display).

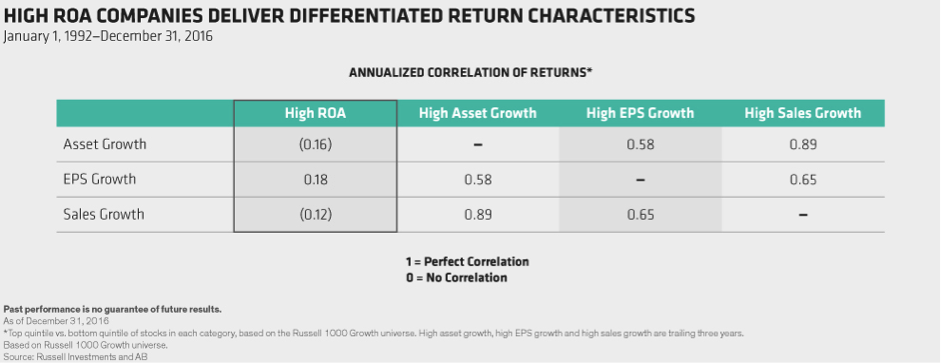

What’s more, shares of companies with high ROA, tend to be relatively less correlated to traditional growth characteristics (Display). This offers another benefit for investors seeking to secure differentiated performance patterns.

We’re not suggesting that earnings aren’t important. However, earnings shouldn’t be viewed in a vacuum. Profits must be put into the context of a company’s underlying income statement, balance sheet and business environment in order to reach meaningful conclusions about the quality of its earnings. By focusing on profitability and returns on investments, investors can differentiate between companies whose growth spurts will be fleeting and those with true long-term growth potential that can withstand the ephemeral effects of an erratic earnings season.

References to specific securities are presented solely to illustrate the research analysis herein and are not to be considered investment advice or trade recommendations, and it should not be assumed that investments in any specific security was or will be profitable. The views expressed do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio management teams.

Frank Caruso is the Chief Investment Officer for U.S. Growth Equities at AB.