By Elena Popina

(Bloomberg) --You’ve probably heard: it’s the longest bull market ever. You’ve probably also heard: no it isn’t. What’s the story?

According to a loose consensus, bull markets are rallies that go beyond 20 percent and are never interrupted by a 20 percent fall. In many corners of Wall Street, that means the S&P 500 rally that began in March 2009 is about to surpass all that went before.

Here’s the issue: these definitions aren’t chiseled in stone. They’re not laws of nature -- it’s not even totally clear where they come from. The 20 percent threshold strikes people as arbitrary, spurious, an invention. Pundits disagree on everything from the role of psychology in defining market eras to how strict you should be about the parameters for past ones.

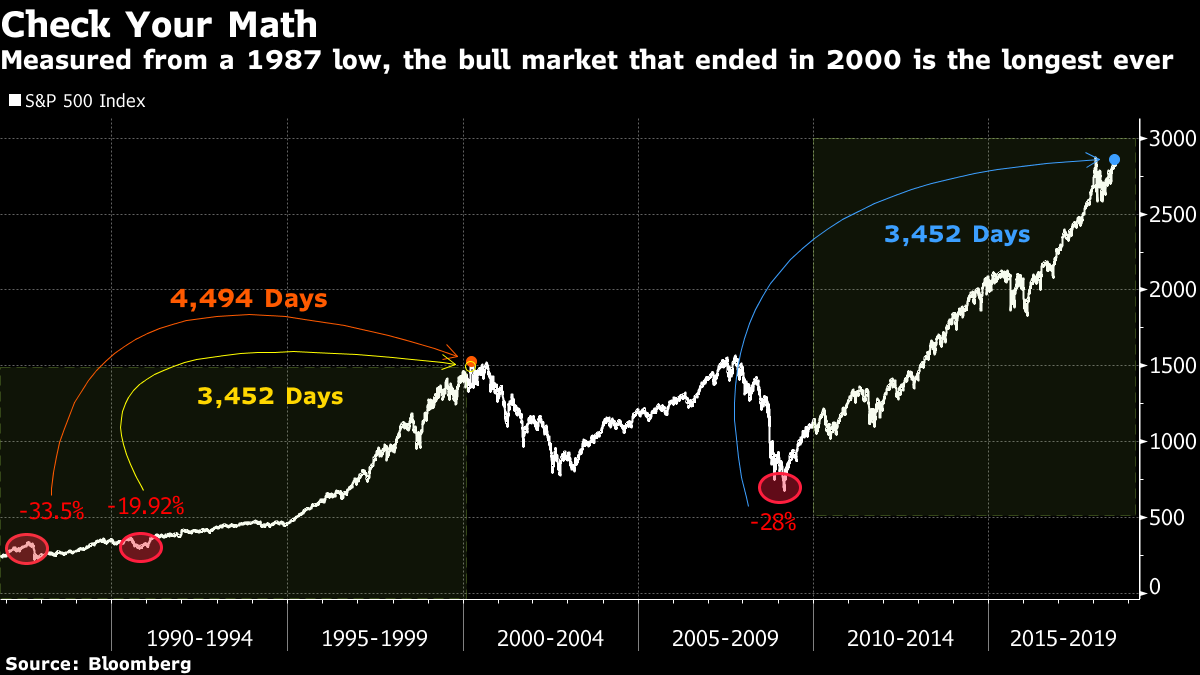

Several objections pertain to measurement. One is how to date the rally this one supposedly supplants -- the dot-com bubble. Traditionally, statisticians have placed the start of the tech rally in October 1990, the bottom of a slide in the S&P 500 that got very close to 20 percent but not all the way. If you refuse to call that 19.92 percent drop a 20 percent drop, the advance gets longer, and today’s would need a thousand more days to exceed it.

“If you round the data, you’re going to get a certain number of bull markets. If you don’t round, you’re going to get a different number,” Justin Walters, co-founder of Bespoke Investment Group LLC, said by phone. “If you want to do that, that’s fine, but it’s not using the standard 20 percent definition.”

When a tradition coalesces on Wall Street, it’s hard to dislodge. The best argument for considering 1990 a break in a bull run is probably that much of the old guard considers it so. Different researchers give different verdicts -- sometimes at the same shop. For better or worse, those eight 100ths of a point have been glossed over by history, leaving the 1990s run to begin in 1990.

Another analytical point: Who cares? Equities have been in good shape for years -- maybe leave it at that. The stock market isn’t a geometry project, skeptics note, it’s a tool for capital formation, something people depend on for retirement. What difference does it make if the chart hews to a pattern in which declines of 20.1 percent matter and 19.9 percent don’t?

“We like records, we like round numbers, it’s a concept we like to talk about and tweet about,” Charlie Bilello, director of research at Pension Partners LLC, said by phone. “But no one in his right mind would use this as an investment strategy.”

Another issue pertains to the custom of dating bull markets from trough to peak. Accordingly, since the S&P 500 was higher in January than it is now, it’s possible the bull market ended then. Sure, stocks are a lot closer to highs at the moment than they are to a 20 percent decline. But who knows?

Here’s a rundown of other ways that people say 3,452 days without a 20 percent decline do not a bull market make.

Where to Start?

It’s been nine years, five months and 12 days since the S&P 500 hit a 13-year low on March 9, 2009, the date considered by many to be the start of the equity recovery. Not so fast, say skeptics. According to them, a bull market begins not when the stocks reach a bottom, but after an interval of recovery --like when the market breaches its previous high. Viewed like this, the bull market started on Feb. 19, 2013, when the S&P surpassed an October 2007 high.

“I will not be popping the champagne for the bull market on Aug. 22,” said Jeffrey Hirsch, editor of the Stock Trader’s Almanac. “Everyone’s hung up on the record. It’s more nuanced than that.”

Intraday Rout

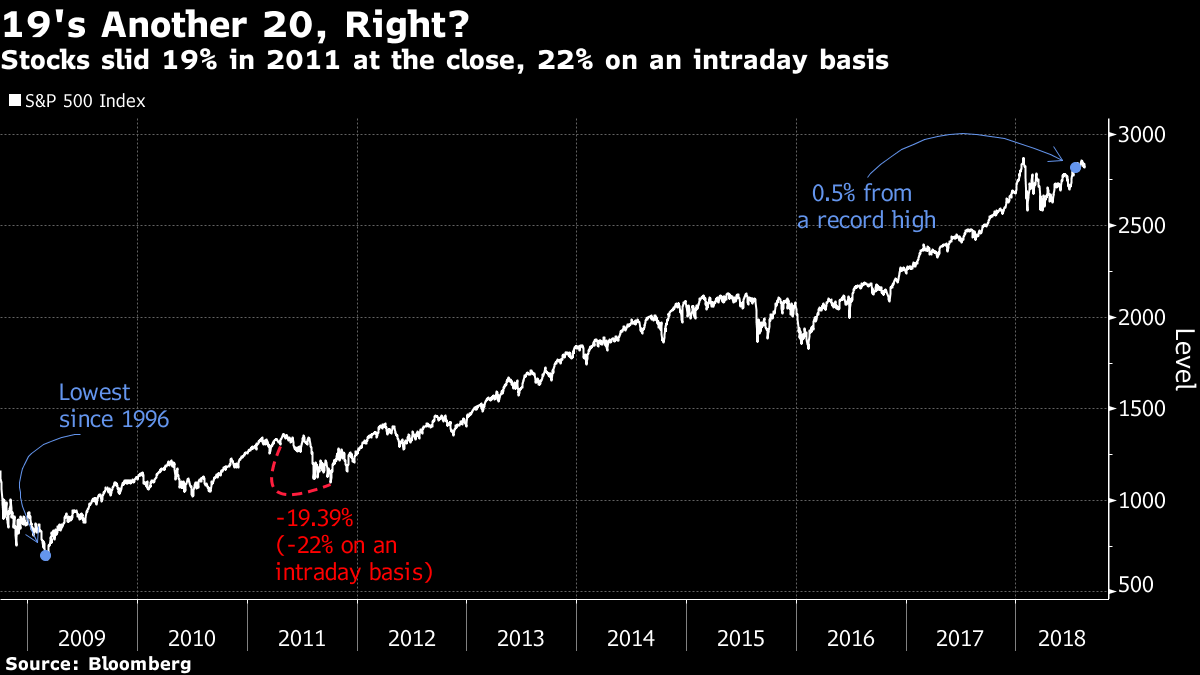

Several gripes pertains to how you calculate a 20 percent drop. Adherents of this view note that, fine, the recovery that started two months after Barack Obama took office hasn’t had a 20 percent decline when measured close to close. But it has had one when measured by the highest and lowest levels recorded during the trading day. Between May and October 2011, the S&P 500 plunged 22 percent on an intraday basis. Just because it skirted the definition based on where it landed at 4 p.m. shouldn’t matter to sensible people.

“There is a lot of sloppy data or historical revisionism or both,” said Mark Hulbert, an editor at Hulbert Financial Digest. “People just blithely assume that that bull market started on March 9, 2009. Depending on who you talk to, there have been one or two bear markets that occurred in that period.”

Global Selloff

A 20 percent selloff is painful, but investors can suffer worse fates. So goes a line of thinking that looks at the long, barren period U.S. markets went through around the time of the yuan devaluation in 2015. Even though the drop never exceeded 15 percent, the S&P 500 went through two 10 percent corrections and more than half its members sustained a 20 percent plunge. A gauge of small-cap companies retreated 27 percent between May 2015 and February 2016 while energy companies lost 30 percent in the span.

“I don’t care what a textbook says, that was a bear market,” said Michael Batnick, director of research at Ritholtz Wealth Management. “It wasn’t just that stock prices were going down, but businesses were in trouble, we had an earnings recession and energy prices were collapsing. That to me is a clear sign of a recession.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Elena Popina in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Courtney Dentch at [email protected] Chris Nagi, Jeremy Herron