By Nir Kaissar

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --Jeffrey Gundlach, founder of DoubleLine Capital LP and prognosticator extraordinaire -- he predicted that Donald Trump would win the presidential election, among other prescient calls -- announced his latest investment idea at the Sohn Investment Conference earlier this month. He recommends that investors buy the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF and short the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (in trader speak, a pair trade).

His timing couldn’t have been better. The Trump rally that has raged since Election Day now looks shaky after all the bombshell revelations that hit the White House this week. The S&P 500 sank 1.8 percent on Wednesday, its worst one-day decline since September of last year. Many on Wall Street are bracing for further declines.

But even if things were going smoothly at the White House, Gundlach’s pair trade would still be appealing. For one thing, U.S. stocks look expensive compared with those of emerging markets. The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500 is 25.7, whereas the P/E ratio of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index is 14, based on 10-year trailing average earnings.

Granted, U.S. stocks have been more expensive than emerging-market ones since 2011, but momentum is now on the side of emerging markets. The price of the Emerging Markets Index has risen above its 50-, 100- and 200-day moving averages. At the same time, the S&P 500’s momentum is weakening. Its price has fallen below the 50-day moving average and is closer to its 100- and 200-day moving averages than at any point this year.

In other words, emerging-market stocks are cheap and strengthening while U.S. stocks are rich and stalling. You don’t need a crystal ball to see which one is the better bet.

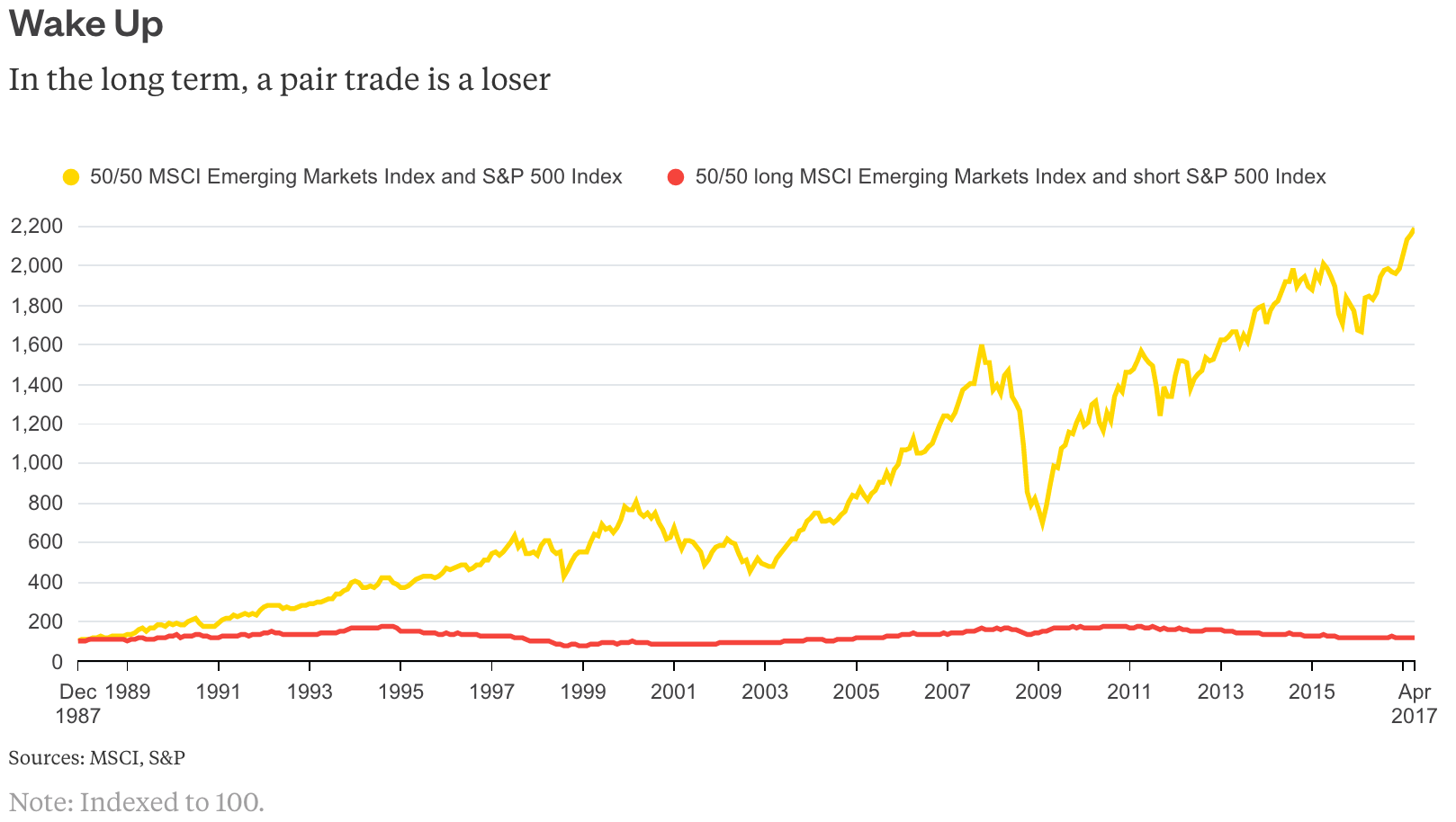

There is one wrinkle, however. Gundlach’s pair trade is -- as its name suggests -- a trade, not an investment. That’s a crucial difference. Consider that a 50/50 long-only portfolio of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index and the S&P 500 would have returned 11.1 percent annually from 1988 through April, including dividends -- the longest period that returns are available for both indexes.

However, a portfolio that is 50 percent long the Emerging Markets Index and 50 percent short the S&P 500 would have returned just 0.7 percent annually over the same time. The reverse would have been even worse. A portfolio that is 50 percent long the S&P 500 and 50 percent short the Emerging Markets Index would have declined 1.4 percent annually.

The sharp difference between the long/short and long-only portfolios is simple math. While the two indexes often decline in the short term, they are likely to trend higher over longer periods. In the long/short portfolio, therefore, the short position will eventually cannibalize the long one, leaving investors empty-handed.

So investors can’t just plop their money alongside Gundlach’s and forget about it. At some point, they’ll have to unwind the pair trade.

But when? This is where the crystal ball becomes foggy. While there’s a long history of valuation data on U.S. stocks, the available data on emerging-market stocks only goes back to the mid-1990s. And since then, there have only been a handful of episodes that resemble the current environment for U.S. and emerging-market stocks.

Not surprisingly, those episodes are clustered around the period from 1998 to 2003. That’s when emerging markets were reeling from back-to-back crises -- the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the 1998 Russian financial crisis -- while the U.S. was in the throes of an internet-induced euphoria. For much of that period, U.S. stocks were more richly valued than those of emerging markets.

And when emerging markets also had positive momentum during that period -- as they did in March 1999, from December 2001 to May 2002, and again from May to September 2003 -- the long/short portfolio beat the long-only portfolio by an average of 2 percentage points over the next year.

Increase the holding period, however, and the long/short portfolio is a loser. Over those same periods, the long/short portfolio lags the long-only portfolio by an average of 7 percentage points annually over three years, 7.3 percentage points annually over five years, and 4.5 percentage points annually over 10 years.

Investors who are tempted to bet alongside Gundlach should set their alarms. There’s an expiration date on his pair trade.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

To contact the author of this story: Nir Kaissar in Washington at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at [email protected]