By Tim Duy

(Bloomberg Prophets) --This rally in equities could be described as “frothy,” but that might not be a sufficiently strong adjective. These days often feel like the late 1990s, when it seemed any company that added “dot-com” to its name was instantly rewarded by investors, even if the label amounted to little more than putting lipstick on a pig. That phenomenon isn’t entirely unlike the bounce in Kodak’s stock price after the company announced the launch of its own cryptocurrency.

It feels like we have been here before, and it didn’t end well for the economy. Will this time be the same?

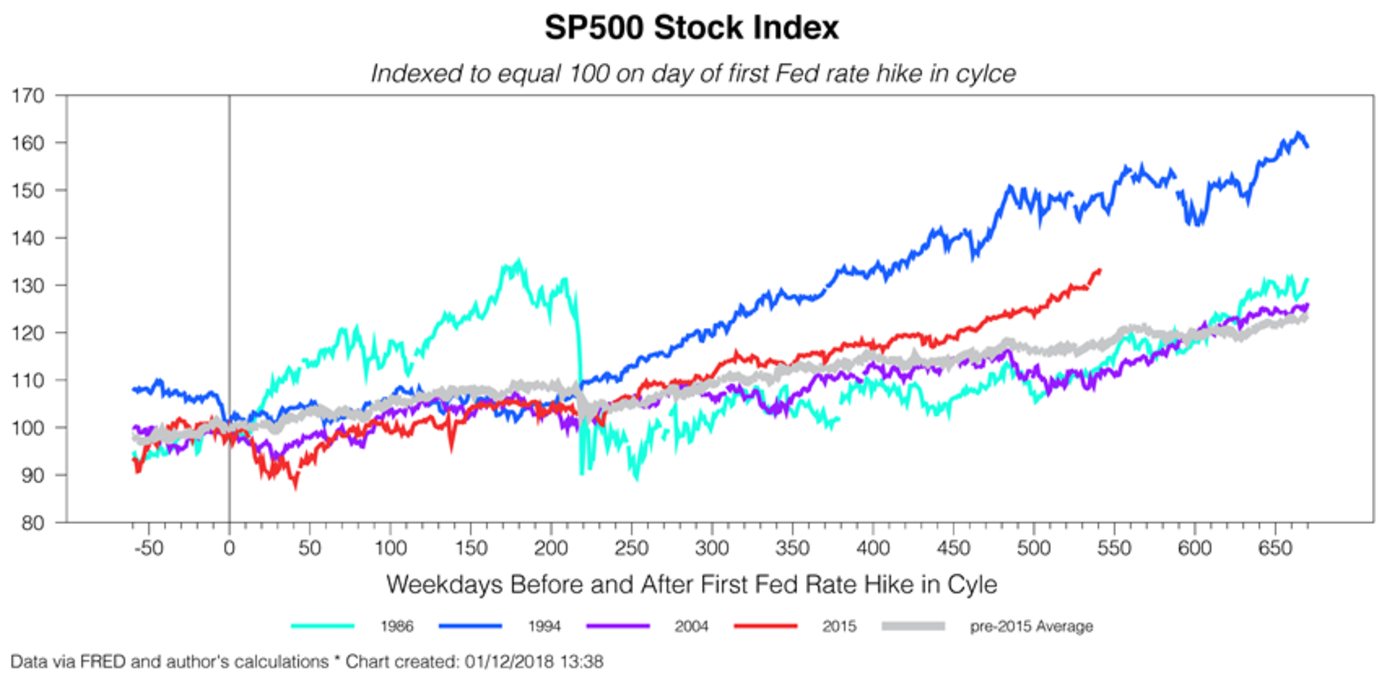

Investors have long worried over excessive equity price valuations. I have tended to be more circumspect about such concerns, particularly as they related to the prospects of an imminent decline in equities. Stocks were simply observing a typical pattern of gains that follows the beginning of a cycle of interest rate increases. Moreover, the lack of recessionary signals suggests little reason to expect widespread profit weakness and hence we should expect that equities are more likely to flatten or rise further than fall.

The second part holds true. There is no reason to believe a recession is imminent in 2018. That tells me it’s still hard to bet against equities, which tend to rise during expansions. That said, the gains over the past two months now appear excessive relative to past cycles:

Don’t interpret this as a market timing call. It’s not intended to warn of a near-term reversal. If the late ’90s taught us anything, it’s that the party can go on for a long time, especially in the absence of an aggressive central bank.

The question is: To what extent are rising equity prices a game Wall Street is playing with itself, or is Main Street deeply involved? In other words, if markets were to crash, would the economy crash as well?

The two are not always related. Equities shed more than 20 percent of their values on Oct. 19, 1987, but no recession followed. In contrast, the market was deeply connected with the economy during the information technology boom, and the two fell apart together.

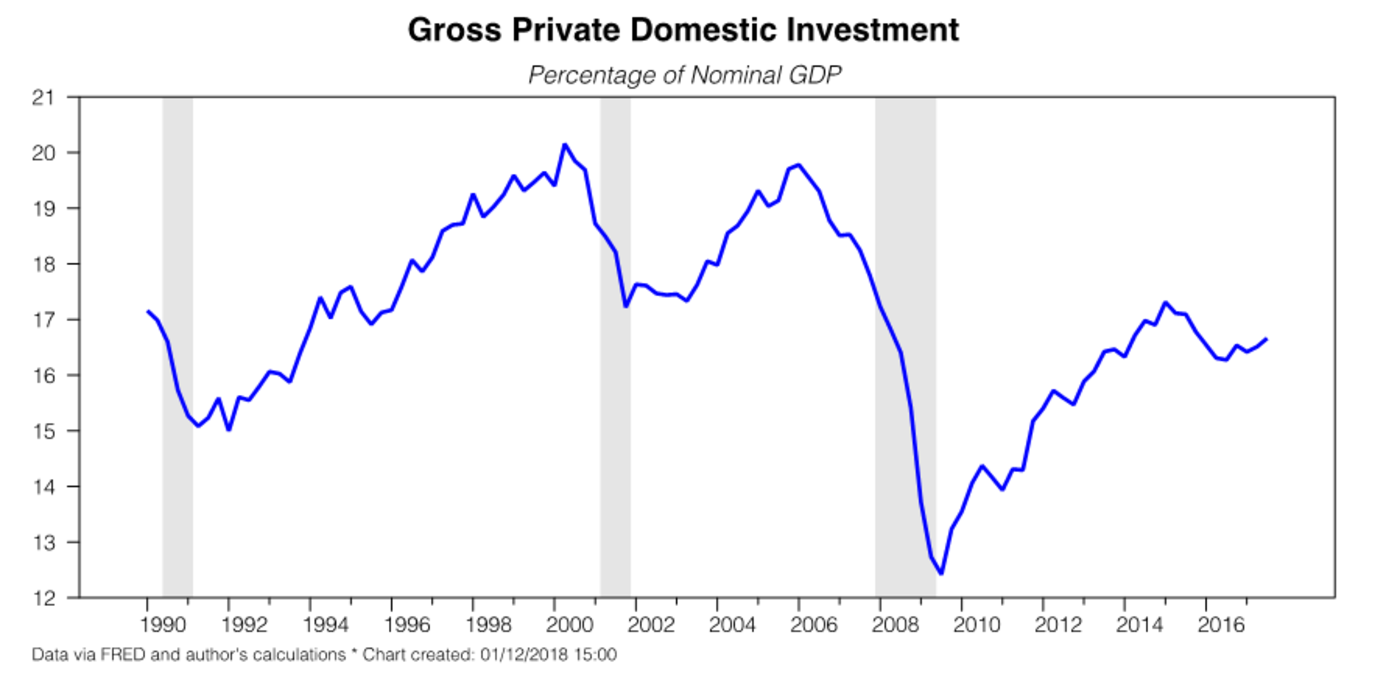

The lack of an investment boom separates this cycle from the last two:

Even if financial excess is growing, it doesn’t look like there’s economic excess to match. This suggests less of a link between asset prices and the economy compared with the last two cycles. That tells me two things: A drop in the stock market is not likely to trigger a recession, and the next recession will be milder compared to the last two. Also remember that the Fed has some room to lower rates should they need to, enough to match the cuts that followed the 1987 crash.

The economic situation can change, of course, exposing imbalances or a shift in activity patterns that leave the economy more vulnerable than it currently appears. Or maybe the cryptocurrency mania runs deeper into actual economic activity than I think. These are certainly on my watch as possible signals the economy is transitioning from “mature” to “late-stage” of the business cycle.

I am also watching how the Federal Reserve responds to the threat of financial market excess. At the moment, the Fed appears unwilling to intervene. New York Fed President William Dudley, for instance, remains calm with the current situation:

One area I might be slightly -- but not particularly -- worried about is financial market asset valuations, which I would characterize as elevated. While valuations are noteworthy, I am less concerned than I might be otherwise because the economy’s performance and outlook seem consistent with what we see in financial markets.

Economic overheating would elicit a Fed response before financial market excess. It is not clear that central bankers could derail such excess without tipping the economy into recession, hence their caution in using monetary policy to tame markets.

As long as economic activity remains fairly restrained as we have seen throughout most of the current expansion, the Fed is likely to remain committed to a gradual path of rate hikes. Moreover, the economy would not likely have the same levels of excess that developed during the information technology or housing booms. This combination would both lengthen the expansion -- and with it the equities rally -- and minimize the extent of any subsequent recession. But if the rally in equities signals a surge in economic activity that threatens to send inflation on an upward path, watch for the Fed to apply the brakes more aggressively.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Duy is a professor of practice and senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon and the author of Tim Duy's Fed Watch.

To contact the author of this story: Tim Duy at [email protected] contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view