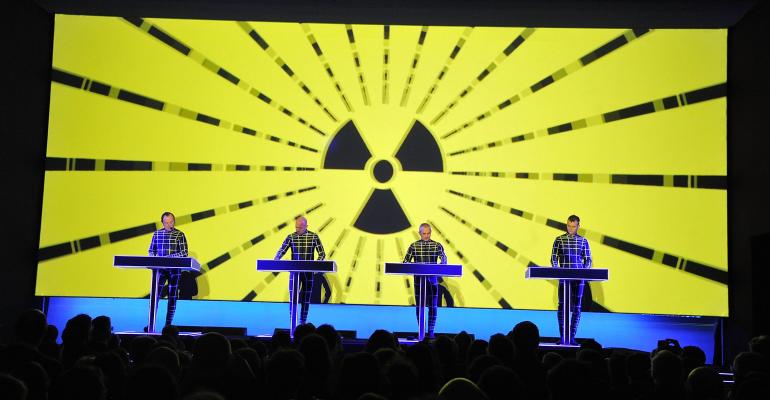

“Sie ist ein Modell und sie sieht gut aus…,” German for “she is a model and looks good…,” are the lead-in lyrics to the synth-pop song Modell by '70s band Kraftwerk. Having just returned from traveling in Germany for more than a week, I am left with nothing to desire as an interested observer of socioeconomic affairs. In short, a usually rigid and understated German society has become the obvious model of economic success and increasing prosperity on a national level. Kraftwerk, loosely translated, is German for “powerhouse,” and in my frame of reference, the German economy, now in its best condition in more than 50 years, continues to power the success of most of the European Union (EU), with many other member nations still struggling to find their socioeconomic equilibrium.

German small talk is not overly engaged in geopolitical uncertainties, especially regarding the brewing conflict involving Eastern-neighbor Russia. Still too familiar are the feelings of a decades-long “iron curtain,” a marker of the symbolic separation between Europe's capitalist West and communist East during the Cold War. Factually, the Germans have a point in their indifference, as the economic exchange between Russia and their country is minimal, comprising only about 3% of total trade. The real, sizable business opportunities are attributable to Germany’s European neighbors; of goods “made in Germany,” 69% were exported to European countries and 57% to EU-member nations in 2013. Last year, the top trading partner (exports plus imports) was France, followed by the Netherlands and China (the U.S. ranked fourth).

Recent trade data reveals the real issues plaguing the EU: a misaligned economic system with incentives and responsibilities that are difficult to balance. Willingly or not, the German government and policymakers around Chancellor Angela Merkel are bound to continue their support of the European financial system, not only based on dedication to the overall “European idea,” but also simply to stay in business. Too dominant is the world's dislike of an “overpowering” Germany, potentially leaving communal interests aside. Not only is a more optimal European economic and fiscal integration required, but politically, it is time to move closer together as well, considering the spread of geopolitical tensions around numerous EU borders, and a United States that, evidently or not, is turning increasingly more within, potentially creating a global power vacuum.

Statutory limitations and populism aside, the European Central Bank (ECB), despite being strongly influenced by the German Bundesbank, will have no choice but to address the increasing “slack” of the European economy. Monetary policies focused only on select powerhouses (or on one, in this case) will prove to be ineffective, or will significantly expedite deflationary forces in much of Europe; in this respect, the outlook for financial markets will depend on the ECB’s particular direction and commitment. Currently, European equities are priced for mediocre economic conditions, and bonds reflect significant risk and an appetite for safe assets. Even against the backdrop of a slightly improving economy, bond yields may stay low for an extended period of time, but equities should be relatively well-priced, especially in a global context.

Market participants that seek exposure to European stocks are still faced with the challenge of correctly interpreting current developments, as well as actions of the ECB. Of particular interest is that the German population has little exposure to financial assets in either the context of its own powerhouse or the global markets. The German Equity Index (DAX) is marking new highs, and yet retail investors lack a true “equity culture:” A meager 13.8% of the German population owns equities (or equity mutual funds), and participation has actually been in decline since 2001.

If domestic retail investors are hardly the primary cause of rising German (or any) stocks, directed funds must originate from institutional sources and/or be speculative in nature, mainly stemming from interest abroad; this in and of itself, will create a challenge when assessing the future opportunity set, as changes in institutional investor behavior and, more importantly, the curbing of “speculative funds” created on the basis of monetary policies (or expectations thereof) may lead German markets lower. A not dissimilar story is currently unfolding in Japan, with most investors in Japanese stocks coming from abroad.

It is comforting to know that rising equity markets, and related investor participation, are not the only recipe for economic prosperity, and the same may hold true for accommodative central-bank policies. The “Mittelstand,” Germany's collaborative of privately-owned small-to-mid-sized companies, mainly with a manufacturing focus, is creating 60% of all jobs and contributes 50% to GDP. With this in mind, I am encouraged by a developing German-style re-industrialization trend in the U.S., but I continue to be concerned in the near-term over financial stimulus distorting asset prices all over the world.

Matthias Paul Kuhlmey is a Partner and Head of Global Investment Solutions (GIS) at HighTower Advisors. He serves as wealth manager to High Net Worth and Ultra-High Net Worth Individuals, Family Offices, and Institutions. For the rest of his blog posts,visit here. You can also follow him on Twitter @MoneyClipBlog.