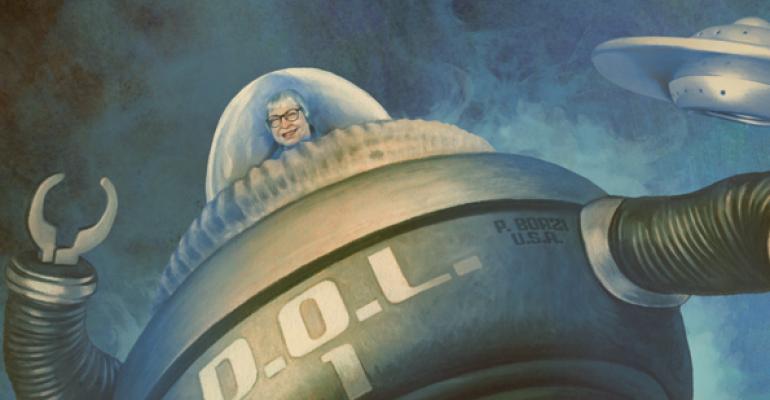

In 2009, President Obama appointed Phyllis Borzi, an attorney and research professor at George Washington University Medical Center’s school of public health, as assistant secretary for the Employee Benefits Security Administration at the Department of Labor.

From the day she was confirmed, Borzi set her sites on tightening up the definition of a fiduciary and the standards to which practitioners must be held when dealing with retirement accounts.

“The world has changed,” Borzi said during the DOL’s fiduciary hearings in March 2011. “In enacting ERISA, Congress recognized that the security of American retirement plans depends on its fiduciaries… Thus, it’s vitally important when we define important terms, like who is a fiduciary, we get it right.”

But the crusade hit a brick wall: Thirty-three Democratic congressmen sent her a signed letter criticizing the DOL for failing to conduct a cost-benefit analysis of the rule and neglecting to coordinate with the Securities and Exchange Commission’s efforts to create a fiduciary rule of its own.

On top of that, Obama was up for reelection and it was unclear how much longer Borzi would have the job. In the latter half of 2012, things at the DOL went quiet.

But just when industry stakeholders thought they didn’t have to worry about the DOL, Obama was reelected and Borzi came back stronger than ever. The sleeping giant woke up in late December, when the DOL put its fiduciary standard on its list of regulatory priorities for 2013, and marked July 2013 as the expected release of a second notice of proposed rulemaking.

The uncertainty around the future rules of the industry has always been a concern—The SEC’s fiduciary standard is still being debated and FINRA’s attempt to force brokers to disclose recruiting bonuses is controversial—but bringing the power of the DOL into the mix could be a game changer.

“We are going to have a new regulator growing in prominence and strength and authority,” says Patrick Farrell, who runs both and independent b/d and a corporate RIA, thus falling under the purview of both FINRA and the SEC.

While we don’t know what Borzi’s rule will look like, it’s expected to expand the definition of a fiduciary to anyone who provides advice to retirement plans, including individual retirement accounts and 401(k)s. That’s a huge market: As of September 2012, total U.S. retirement market assets were $19.4 trillion, according to the Investment Company Institute. Cerulli Associates estimates there are about $5.6 trillion in IRAs alone, projected to reach $8.5 trillion by 2017. In comparison, mutual funds managed $982 billion in variable annuities outside of retirement and $4 trillion of assets in taxable household accounts as of 2011, the ICI says.

While we don’t know what Borzi’s rule will look like, it’s expected to expand the definition of a fiduciary to anyone who provides advice to retirement plans, including individual retirement accounts and 401(k)s. That’s a huge market: As of September 2012, total U.S. retirement market assets were $19.4 trillion, according to the Investment Company Institute. Cerulli Associates estimates there are about $5.6 trillion in IRAs alone, projected to reach $8.5 trillion by 2017. In comparison, mutual funds managed $982 billion in variable annuities outside of retirement and $4 trillion of assets in taxable household accounts as of 2011, the ICI says.

The DOL’s proposal would have a major effect on both registered reps and RIAs. Unless exemptions are made, brokers would have to act as fiduciaries in retirement and IRA accounts, giving up their current compensation model.

Some may simply drop their licenses and go fee-only. Brokerages may only let a small number of reps handle this business and require that they go through some kind of fiduciary training program. Most reps likely won’t bother serving those accounts.

“How many investors will not open up an IRA account or begin the process of saving for retirement because they can’t access the advice and service that they need?” asks Dave Bellaire, executive vice president and general counsel at FSI.

The broker/dealer industry is spending millions of dollars lobbying against it. Meanwhile, RIAs—already acting as fiduciaries under the SEC’s definition—are in a good spot to capture some of those retirement assets.

What’s the Big Deal?

While the SEC is working on its fiduciary standard at a snail’s pace—focusing, instead, on getting its senior leadership in place—the DOL is likely to put a stake in the ground first. That could give it the advantage of defining the debate and provide a glimpse of what’s to come out of the SEC.

If the DOL stays on track, many non-fiduciary advisors will besubject to ERISA fiduciary standards for the first time—one reason that broker/dealer advocates like the Financial Services Institute and SIFMA are arguing to get some form of exemption for IRA accounts.

Many reps receive variable compensation—commissions, 12b-1 fees or revenue-sharing structures—for the funds investors put into in IRA accounts; in many ways, it’s not profitable for reps to service these accounts, which tend to be smaller, without the fees.

“Under ERISA, if you have a conflict of interest and you do full and complete disclosure and there’s no so-called prohibited transaction exemption, then you’ve just given people a road map of how to sue you,” says Marcia Wagner, managing director at The Wagner Law Group. “They have to figure out a way to levelize their compensation, so they don’t have an incentive to skew their advice they proffer to something that would give them more money, or churn.”

Critics of the proposal say they are concerned that the DOL’s rule is in conflict with the SEC’s proposed fiduciary standard. Under the SEC, investment advisors can have a conflict of interest as long as it is disclosed to the client, says Bellaire. Under the DOL’s effort, any activity that poses a conflict would be prohibited. In other words, no amount of disclosure or client sign-off would allow the advisor to sell commission products in retirement accounts.

Many believe the rule won’t come down as strict as the original proposal, with some sort of exemption for broker/dealers or IRA accounts. Indeed, the DOL has indicated that it intends to release some PTEs (prohibited transaction exemptions), which would define a series of steps to avoid the prohibited transaction, Bellaire says.

“There are so many firms with so much lobbying power lining up against this, it’s hard to see as strict a set of regulations coming through on the IRA side as exists on the 401(k) side,” says Bing Waldert, director at Cerulli Associates.

“I believe there might be some loosening of standards with respect to IRAs,” Wagner says. “Mind you, the DOL has not said that. They haven’t tipped the hat in that area.”

“In fact, in the promulgated regulation that was withdrawn [they] specifically said that IRAs are held to the same standards, that they were not exempting.”

Ron Rhoades, president of ScholarFi and former chair of NAPFA, says exemptions will only be granted if they’re in the interest of the plan sponsor and participants; there’s not likely to be one for revenue sharing, he believes. Instead, he says, the rule would force the brokerage to switch to investment advisor platforms for these accounts and charge levelized fees for this advice.

“I think the big fear that the broker/dealer industry has is that basically the broker/dealer industry is a distribution system for investment products, whether it be IPOs or mutual funds or annuities,” Rhoades says. “I could see the demise of the broker aspect of the firm completely, and moving more to discount broker platforms like Schwab, TD Ameritrade, Fidelity.”

Goodbye, Commissions

But broker advocates say the economics don’t support advisors working with small IRA accounts. The brokerage industry’s position has been that small retail IRA investors are largely serviced by the IBD market using load and commission-based funds. If advisors can’t earn a commission on a smaller account, it’s not profitable for them and they’ll likely give up that business.

For example, if a broker now has to charge a 1 percent advisory fee on a $25,000 account, he or she is only earning $250, versus a 3 percent load and a 25-basis-point trail for a typical A share, says Investacorp’s Farrell.

“If you’re restricted to only form of compensation—and in this case that would be an advisory fee—and there’s reams of paperwork, disclosures, you have to be careful about crossing a line accidentally, a lot of people will give up servicing the smaller accounts,” Farrell says.

He believes commission-based advisors will give up IRA accounts $25,000 or smaller, while they’ll keep anything $100,000 or over.

“Most people who are coaching us are saying, ‘You got to get rid of the small clients, Bob,’” says Bob FitzSimmons, president and founder of Bob FitzSimmons, Inc. in Lincoln, Neb. “‘You can’t be productive in servicing those clients when their revenue is very small.’”

FitzSimmons is a dually registered advisor with Investacorp, so he’d have to shift some of his IRA assets over to the RIA side. His average IRA account is $50,000 and up. The administrative aspects of servicing fee business are particularly worrisome.

“It’s going to be a pain. And there won’t be much revenue generated off of it,” FitzSimmons says.

According to a study by Oliver Wyman in 2011, 10.7 million brokerage IRAs would not have enough assets to meet advisory IRA account-opening minimums at the same firm (based on account opening minimums at the time the study was conducted). The Wyman IRA study was submitted to the DOL on April 12, 2011.

“Our concern is that it will reduce access to advice, products and services and reduce the choices available to investors,” says FSI’s Bellaire.

A Running Start

While brokers have been concerned that they’ll have to change their business model, RIAs haven’t paid much attention to the DOL’s fiduciary rulemaking because it wouldn’t mean a drastic change for them, says Skip Schweiss, managing director of TD Ameritrade Institutional. RIAs are already acting as fiduciaries under the SEC, and most are fee-based.

Instead, the rule could mean that a lot of IRA accounts that brokers no longer want to serve are up for grabs.

“This is $5 trillion worth of assets that could suddenly come under an ERISA fiduciary standard,” Schweiss says. “There may be larger accounts that may be more up for play than they are today if the brokerage industry, in fact, backs away from that market, due to the new fiduciary standards.”

While the brokerage industry is now focused on lobbying, it will take some major adjustments to its business model if and when the rule takes effect. Louis Harvey, president and CEO of Boston-based research firm Dalbar, estimates that will take two years.

“The smart RIAs will have a running start, no question about it,” he says. “In those two years, between now and when it does take effect, the RIAs can monopolize the market because I can assure you the broker/dealers and the registered reps are going to be fighting it.

“So one of the things that the RIAs can do tomorrow morning is to go to their clients and say, ‘Listen, I am a fiduciary. I act in your best interest.’ By the time the brokers come on board saying, ‘I too am a fiduciary,’ they’ll have lost the business.”

And there’s a lot of market share to capture. Cerulli expects annual IRA rollover contributions to reach $451.1 billion in 2017, compared to $315.7 billion at year-end 2012. Advisors capture 50 percent of rollovers representing 66 percent of total rollover assets, says Waldert.

Wagner doesn’t buy the idea that these smaller IRA clients are not profitable.

“If you’re going to be in the business for a while, you’ve got to look at the potential client, look at what they could potentially be worth, determine if they can refer you other business.” she says. “I think they have to have scalability.”

Wagner says RIAs should do a market survey of their geographic area to find out where the IRA assets are, who’s doing the rollovers, and what brokers are capturing them. She expects a lot of RIAs to merge, consolidate or partner with broker practices serving IRA clients.

And small accounts may turn out to be big accounts, says Amy Glynn, president and founder of the Pension Resource Institute. When Glynn was at Smith Barney, she says most advisors only wanted to work with rollovers over $50,000. But 85 percent of the time, clients with $15,000 to $25,000 in 401(k) balances ended up with more than $500,000 in investable assets because they had assets elsewhere.

“I feel like advisors are cutting their nose off to spite themselves and saying, ‘Oh we only want the big rollovers.’”

The New Face of Fiduciary

Industry stakeholders and lawmakers alike have criticized the DOL for its failure to coordinate with the SEC on its fiduciary standard. This criticism was one thing that prompted the DOL to repropose the rule, and observers say the DOL is coordinating with the SEC this time around. “I think we’re going to see a little bit of the influence there of whatever the Department of Labor comes up with in terms of what happens at the SEC,” says Rhoades.

Rhoades says the DOL has hired a team of economists to conduct an economic analysis of a fiduciary standard, one that would most likely be shared with the SEC.

Further, the original DOL proposal contained a so-called “seller’s exception,” which would allow products to be sold to plan sponsors and participants as long as it was not advice, Rhoades says.

That means the DOL is going to define what constitutes personalized investment advice, something the SEC has struggled to define for years. If the SEC applies a fiduciary standard to broker/dealers, it will also have to draw that line.

The SEC and FINRA are for many still the focus of the debate when it comes to the future regulations of financial advisors—but with the weight of the DOL behind it, and a post-presidential election mandate to enact the priorities of Obama’s administration, Borzi’s fiduciary initiative is the one the industry should really be watching.