By Ben Steverman

(Bloomberg) --If you have a 401(k) plan at work, there’s a good chance that you’re saving more for retirement because of Richard Thaler.

The Nobel prize for economics tries to recognize important research with far-ranging consequences—but Thaler, awarded the prize Monday, may be its first winner to have had an almost immediate effect on millions of people’s paychecks.

Over the last few decades, as more and more American employers killed off their pensions, workers were offered 401(k)s or similar retirement plans, with defined contributions instead of defined benefits.

These voluntary accounts should have worked, in theory. Standard economic theory assumes people act rationally: Workers, left to their own devices, should save and invest properly to meet their long-term goals.

But Thaler and other adherents of behavioral economics pointed out that workers saving for retirement can be their own worst enemies. Without help, Thaler argued, they’ll never retire. “Probably [behavioral economics’] biggest impact is changing the way retirement plans are run,” Thaler said in a speech at the CFA Institute annual conference in May.

For years, Thaler championed the idea that employees should be “nudged” into joining retirement plans, a concept known as automatic enrollment. Rather than waiting for workers to fill out 401(k) paperwork, employers should automatically sign them up for the plans. If the employees aren’t interested, they can always opt out.

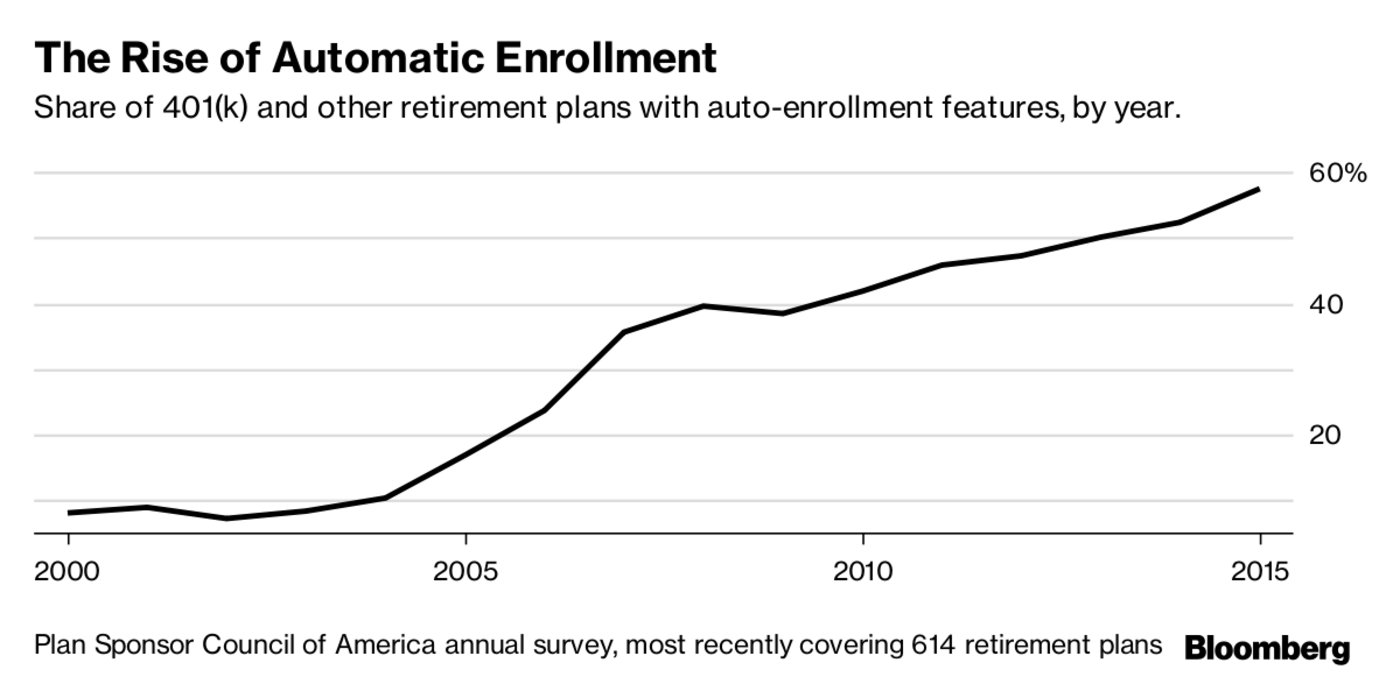

In a survey by the Plan Sponsor Council of America (PSCA) last year, 58 percent of plans were automatically signing up workers. That’s up from just 8.1 percent in 2000.

Thaler didn’t come up with the idea of automatic enrollment, even if he helped popularize it in the 2008 bestseller he co-authored with Cass Sunstein, “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.” Thaler did, however, develop the notion of automatic escalation, also called “save more tomorrow,” along with Shlomo Benartzi, a behavioral economist at the University of California at Los Angeles.

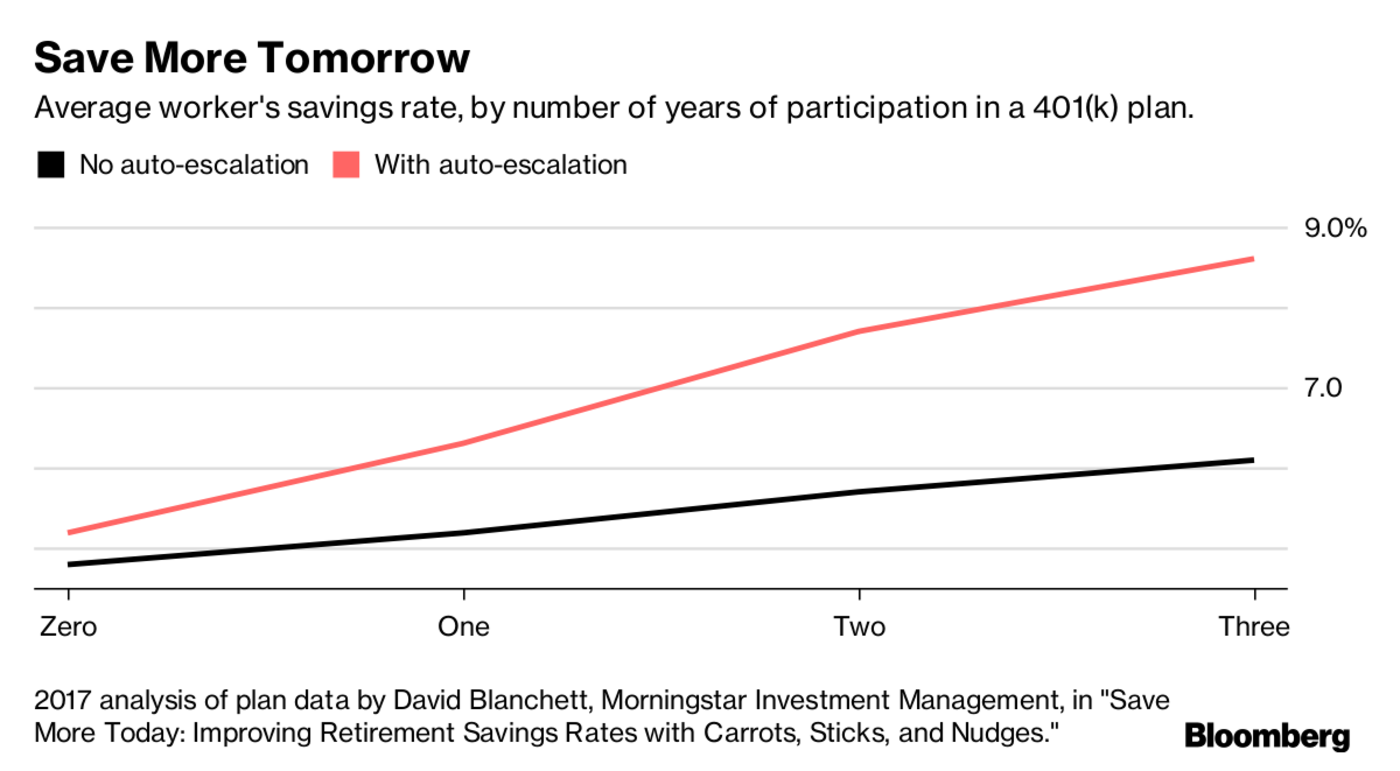

The goal of auto-escalation is to boost how much workers are saving. Setting aside 15 percent of your salary—an appropriate goal for many middle- and upper-income workers—can feel impossible. Auto-escalation addresses this by nudging workers to agree to future increases in their savings rates, usually by 1 percentage point each year. A majority of employers now offer some kind of auto-escalation feature, according to the PSCA, though often workers need to proactively sign up for the option.

Automatic escalation can have a big impact on savings rates, according to a recent analysis by David Blanchett, head of retirement research at Morningstar Investment Management.

According to research by Jack VanDerhei of the Employee Benefit Research Institute, the combination of auto-enrollment and auto-escalation can substantially boost a worker’s chances of retiring with enough income.

In Thaler’s world of defaults and nudges, much depends on getting the details right. The wrong kind of “nudges” can be destructive. Many companies encourage workers to invest much of their retirement in company stock, something Thaler has argued is too risky for workers.

He also says many companies are encouraging workers to save too little. “One problem with automatic enrollment is most firms start people out at too low a rate,” he said in his May speech.

Still, the best-designed nudge in the world won’t get somebody to save enough for retirement if she simply isn’t being paid enough. Thaler’s nudges also can’t reach the millions of Americans who don’t have retirement plans at work—at least not yet.

That may change. Several states are setting up automatic individual retirement accounts (IRAs) aimed at the third of workers who don’t have access to 401(k)s or pensions, and the details of many of those new plans seem ripped from the pages of Thaler’s research.

Oregon, which launches the first auto-IRA program this month, will start workers out saving 5 percent of their salaries, unless they object. And their contributions will auto-escalate every year by 1 percentage point, rising until they hit 10 percent.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Samantha Schulz at [email protected]