(Bloomberg) --Humans learn the concept of fairness at a very young age. After all, it doesn’t take long for a child to start whining about a sibling who gets an extra serving of ice cream. As the Republican-controlled Congress tries to push through tax reform this year, one group of Americans may similarly question why it’s coming up a scoop short.

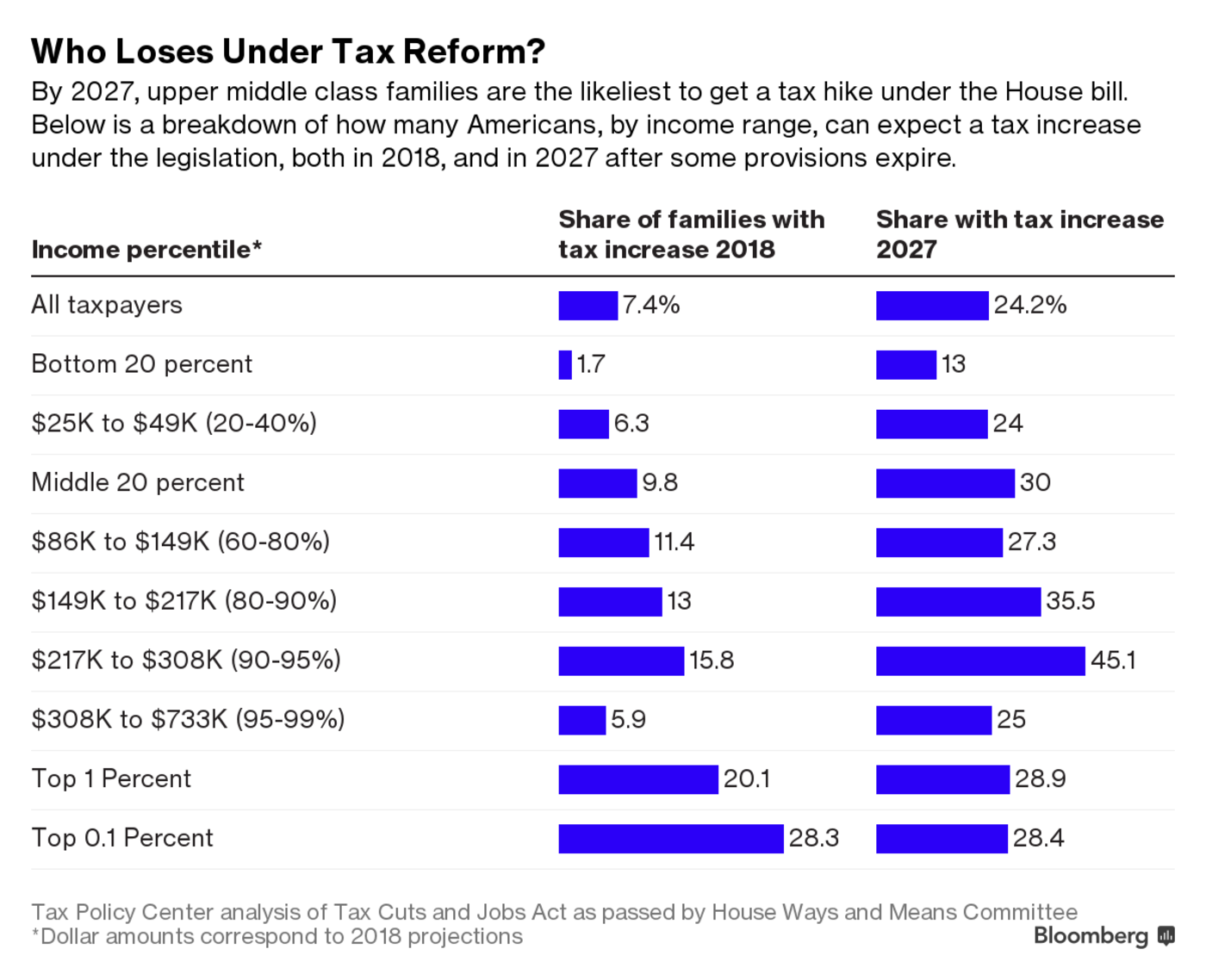

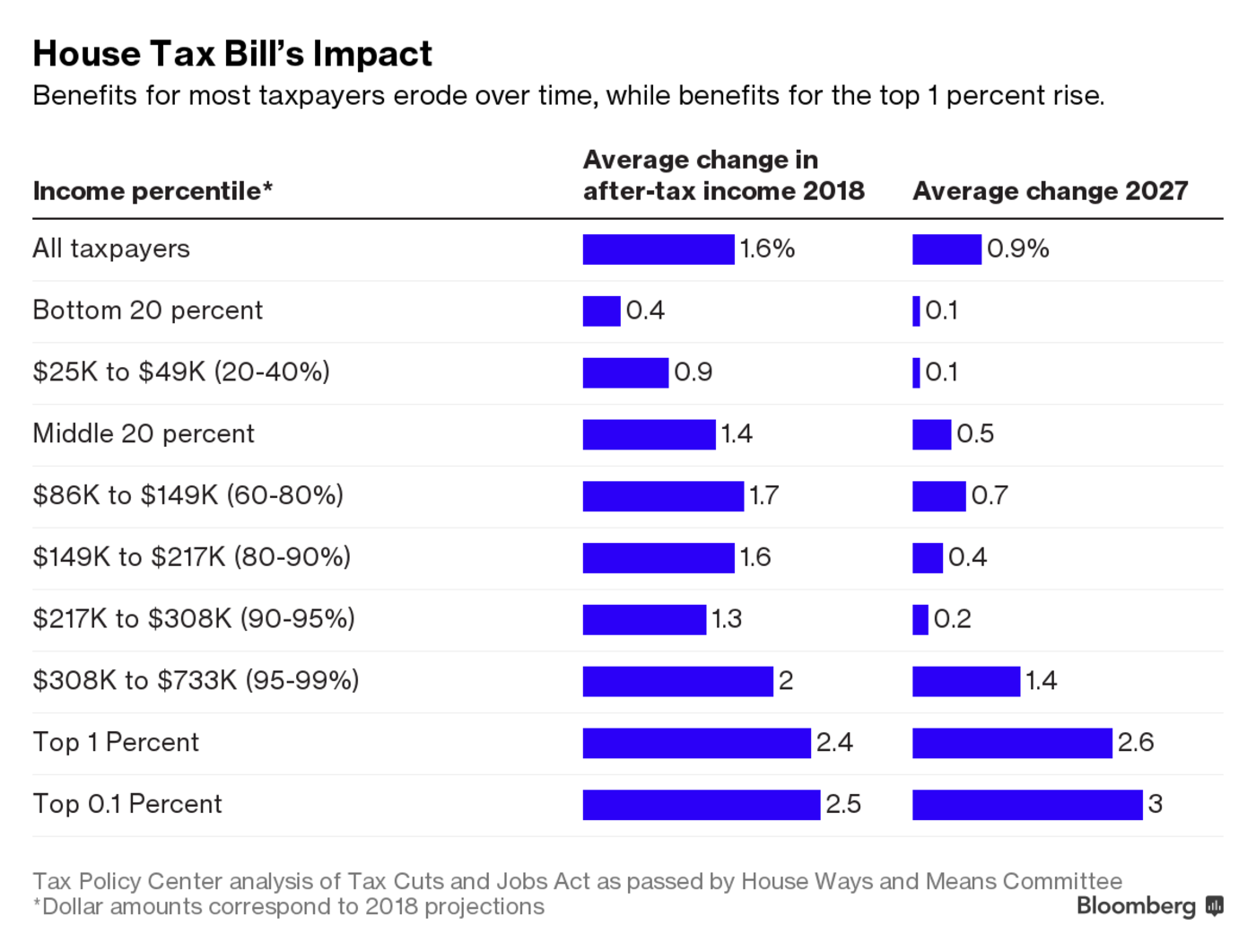

The upper middle class gets relatively few benefits and a disproportionate number of tax hikes under the $1.4-trillion Tax Cuts and Jobs Act approved by the U.S. House of Representatives last week. Families earning between $150,000 and $308,000—the 80th to 95th percentile—would still get a tax cut on average. But by 2027, more than a third of those affluent Americans can expect a tax increase, according to the Tax Policy Center.

If the House bill becomes law, overall benefits for the upper middle class will start out small, and later vanish almost entirely.

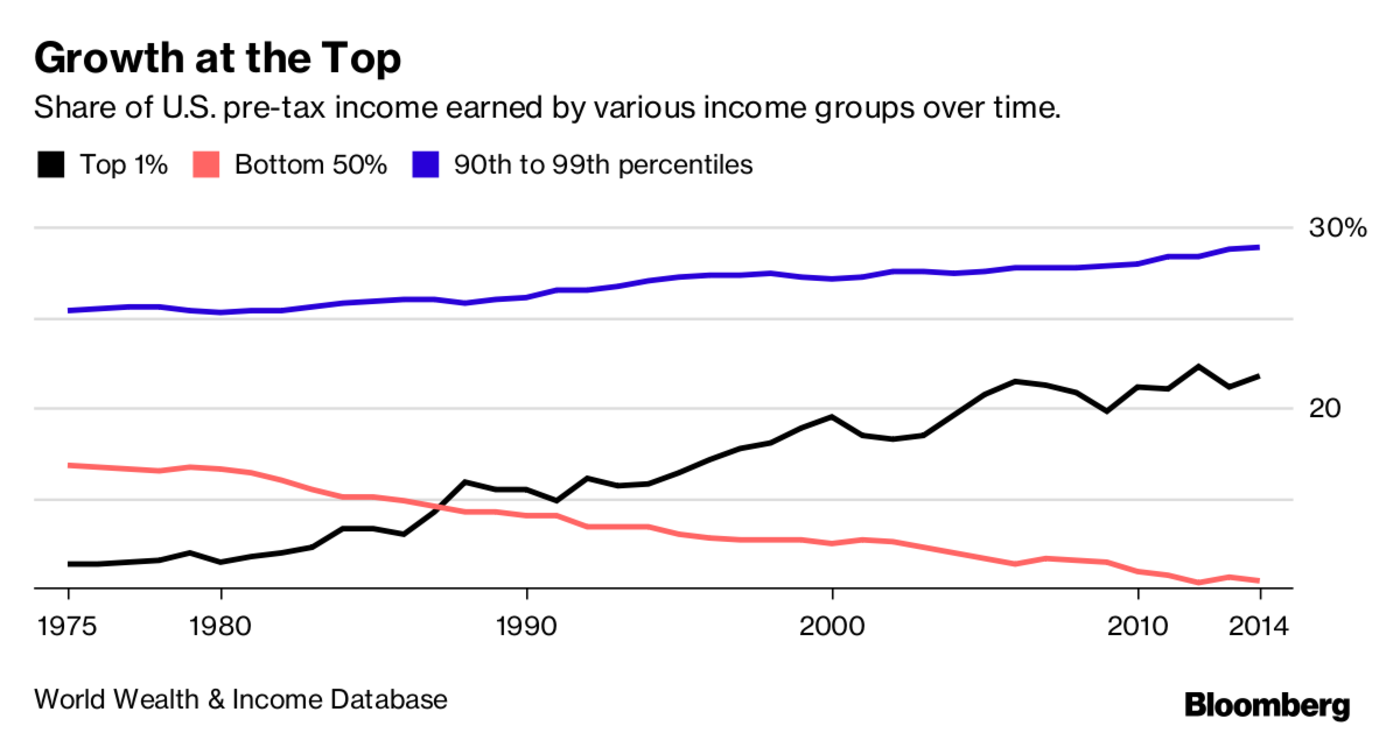

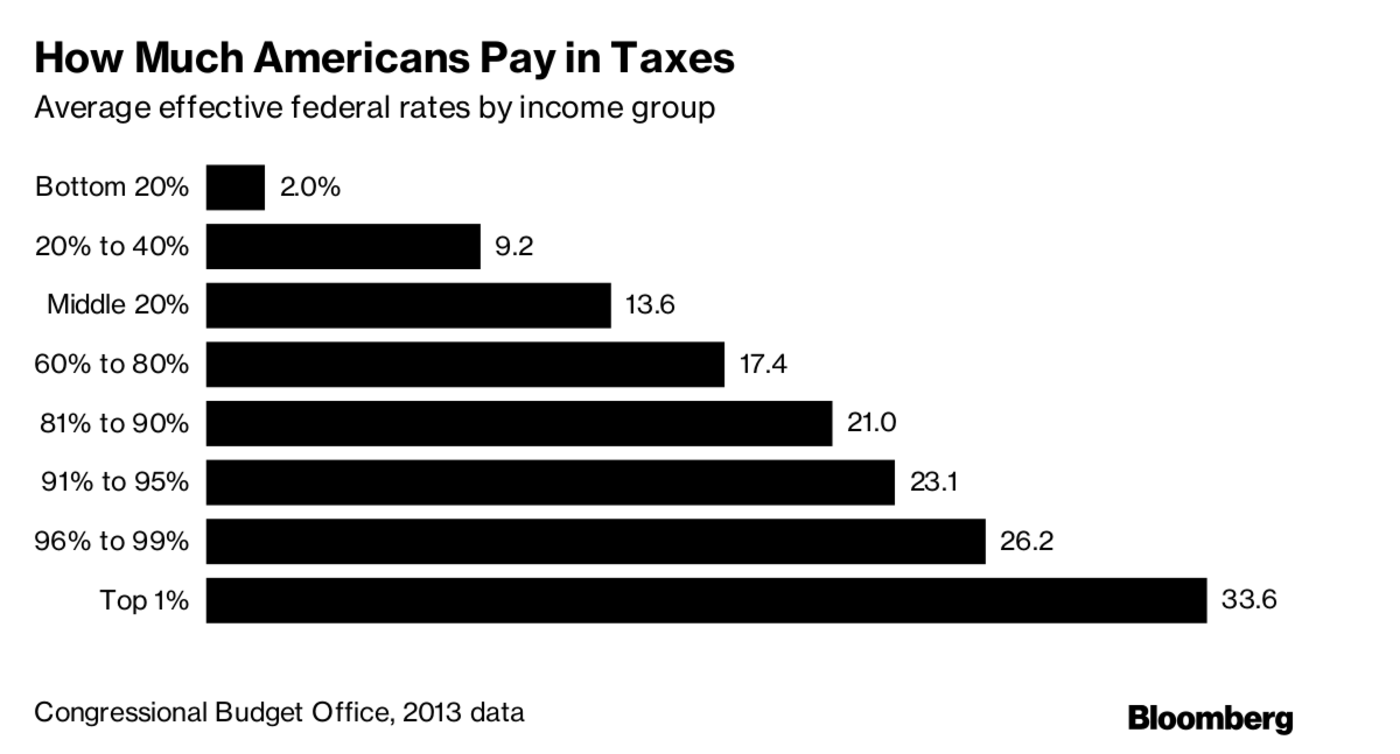

Is this fair? Some argue it’s only right for the upper middle class to carry a heavier burden. This is because the top fifth of the U.S. by income has done pretty well over the past three decades while the wages and wealth of typical workers have stagnated. People in the 81st to 99th percentiles by income have boosted their inflation-adjusted pre-tax cash flow by 65 percent between 1979 and 2013, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That’s more than twice as much as the income rise seen by the middle 60 percent. (The top 1 percent, meanwhile, saw their income rise by 186 percent over the same period, but that’s another story.)

“Many upper-middle-class families will tell you they do not feel wealthy,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a right-leaning think tank. “Their standard of living [is] closer to the middle class than to the top 1 percent.” The income numbers don’t tell the whole story, he explained. The upper middle class is weighed down by high costs: Affluent workers live in expensive areas, pay a lot for real estate and daycare, and are taxed far more than Americans further down the ladder.

Richard Reeves, a senior fellow at the left-leaning Brookings Institution, isn’t buying that argument. He’s the author of “Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do About It.”

“There’s a culture of entitlement at the top of U.S. society,” Reeves said. While others focus on rising wealth of the top 1 percent, Reeves argues that the gap is widening between the top 20 percent and everyone else. The upper middle class is guilty of “hoarding” its privileges, using its power to skew the job market, educational institutions, real estate markets, and tax policy for its own benefit, he contends.

“The American upper middle class know how to take care of themselves,” Reeves said during a presentation at the City University of New York last week. “They know how to organize. They’re numerous enough to be a serious voting bloc, and they run everything.”

So by his measure, the tax legislation’s disproportionate hit to the upper middle class is indeed fair.

A family earning $240,000 a year is bringing in four times the U.S. median household income of $59,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. All that money, along with the upper middle class’s political power, buys some huge advantages, Reeves said. For example, affluent parents compete for access to the best schools, bidding up home values in the best school districts. Then, they use zoning rules to prevent new construction, keep property values high, and prevent lower-income Americans from moving in. In the process, children of this demographic end up at the most prestigious universities, nab the best internships and jobs, and ultimately join their parents at the top of U.S. society.

The very existence of the House tax bill rebuts Reeves’s argument that the upper middle class is in a position to manipulate Washington. (The Senate is considering its own tax legislation, which differs from the House bill in several ways.) Compared with middle class Americans, the upper middle class is less likely to see marginal tax rates fall under the House legislation. The bill also limits or scraps entirely some of the group’s favorite tax breaks, especially deductions for state-and-local taxes, and medical expenses, and tax breaks for education.

If you’re part of the upper middle class and concede you should be paying more, don’t count on wealthier groups making the same sacrifice—at least under the House bill.

While a repeal of the alternative-minimum tax helps some people with incomes below $300,000, it’s more likely to benefit those on the higher wealth rungs. The very rich, including President Donald Trump, who has been pressing for a legislative victory before the end of his first year in office, would benefit from a repeal of the estate tax, lower corporate tax rates and a lower “pass-through” rate on business income. The House bill explicitly tries to limit the pass-through benefit for doctors, lawyers, accountants, and other high-earning professionals—traditional denizens of the upper middle class.

This all may seem terribly unfair to members of the upper middle class, but there are some provisions they can take solace in. The bill leaves untouched some sweet tax breaks that predominately benefit people with lower six-figure salaries, such as 529 college savings plans and 401(k)s and other retirement perks. The CBO calculates that two-thirds of the government’s costs for retirement tax breaks go to the top 20 percent.

But beyond these few exceptions, much of the upper middle class will still take it on the chin.

And maybe they should. Higher taxes on the upper middle class make sense to some liberal tax experts—but only if the proceeds are used the right way, they said, for things like better health care, more affordable college, and rebuilding infrastructure. Under the House bill, though, any new tax revenue is used to offset tax cuts—much of which will benefit the super wealthy and corporations, especially over time.

“There would be a lot of people in the country who would be willing to chip in for those goals,” said Carl Davis, research director of the left-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. In the House plan, however, the upper middle class is “going to pay more for a bill that’s going to grow the national debt, and provide the lion’s share of the benefits to corporations and their shareholders.”

Riedl, who has advised Republican candidates, argues the upper middle class should get a more generous tax cut under GOP tax reform. “It’s hard to argue the upper middle class is not currently paying its fair share,” he said. Reeves said the U.S. should ultimately tax the upper middle class more—but “the top 5 percent more still.”

Looking at Republican tax plans, Reeves said, “it’s like they only read half my book.”

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at [email protected]