(Bloomberg) --Millions of American workers are frozen out of their companies' pension plans. Maybe you get a 401(k), if you're lucky. But the traditional pension is dead.

Unless, perhaps, you're already retired.

It still lives for millions of older Americans who worked and qualified for their pensions in another era. Today's retirees are living pretty well, new research finds—much better than previously thought.

The usual way to measure people’s economic well-being is to ask them. But sometimes surveys confuse people, especially about what qualifies as income.

A new paper by U.S. Census Bureau researchers Adam Bee and Joshua Mitchell uses a Social Security Administration database of 2012 tax filings and other earnings data to check on those survey responses. Older Americans, it turns out, are underestimating their income—by a lot.

The median U.S. household 65 or older earned $44,400 in 2012, those data show, a figure 30 percent higher than the median given in the census’s Current Population Survey from that year. And whereas the original survey found that 9.1 percent of Americans 65 and older were living below the poverty line, the new study puts their poverty rate a full two percentage points lower, at 6.9 percent.

The main reason for the discrepancy: Many of the people surveyed aren't including retirement benefits in their reported income. While just 44 percent of the older survey respondents reported retirement income, tax filings and other data show the actual share getting it is 68 percent.

The most popular retirement benefit among older Americans is still the traditional pension, collected by 56 percent of households 65 and older. Withdrawals from individual retirement accounts (IRAs) were taken by 32 percent of older households, and about 5 percent took money directly from 401(k)-style defined-contribution plans.

Many people think of the proceeds of pensions and IRAs as savings, not income, and they're not necessarily wrong. But that's not how economists or tax collectors generally do. Pensions and retirement accounts include not just the money you've personally saved—usually without paying taxes on it—but also your employer's contributions and any investment gains over the years.

And if you don't include that money in your reported income, you end up looking—to the Census, anyway—much poorer than you are. It means a retiree who regularly cashes in the proceeds from a $2 million IRA can appear financially indistinguishable from a destitute retiree living on Social Security alone.

Previous studies have found that Americans' incomes tend to drop sharply when they retire. This new study, by defining income more broadly and tracking incomes over more than a decade, finds the newly retired have much less trouble keeping up their lifestyles than previously thought. "We do not find large, abrupt declines in income or increases in poverty upon retirement," Bee and Mitchell write.

And there's more good news: Retirees are less dependent on Social Security, the paper finds, than previous estimates have suggested.

Previous studies had also found that poverty rates were more than 50 percent higher for people 85 and older compared to retirees in their late 60s and early 70s—suggesting that the longer you live, the more likely your money is to run out. The new estimates find poverty rates worsening much more slowly with age, rising from 6.7 percent for people 65 to 74 years old to 7.6 percent for those 85 and older. (While poverty rates are lower overall in the new study's estimates, its authors still find that older women are poorer than older men: The 2012 poverty rate for older women was 8.5 percent, compared with 4.9 percent for older men.)

If older Americans have more economic resources, that's something to celebrate. But the study's conclusions are based on 2012 data, and economic realities for retirees are changing quickly.

The authors, who plan to update their analysis when they get access to more recent data, warn that their latest findings "cannot easily be extrapolated to future retirees."

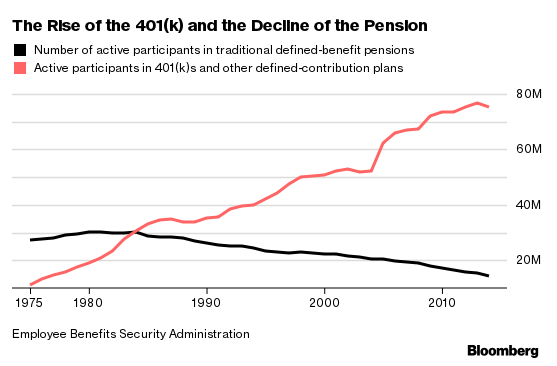

Workers today might be diligently saving in 401(k)s and IRAs, but they're largely frozen out of the traditional pensions that guarantee a fixed income for life: The number of active participants in traditional pensions peaked in 1980 and has been steadily dropping ever since. And many of the remaining traditional pension plans, in both the private and public sectors, are facing financial difficulties.

Younger Americans are also worse off in other ways. Wages, stock markets, and real estate values were rising quickly when older Americans were working, but current workers have suffered long periods of stagnant wages and two major market crashes since 2000. The median wealth of Americans 62 and older leapt 40 percent in just a generation, a St. Louis Federal Reserve analysis found—but the same time, from 1989 to 2013, the typical net worth of younger families plunged, by 31 percent for the middle-aged and by 28 percent for families younger than 40.

The result: A widening wealth gap between America's old and young.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Samantha Schulz at [email protected]