(Bloomberg) -- It’s surprisingly easy to lose track of your retirement savings, leaving them to be eaten up by inflation and fees—or even seized by the state.

Americans jump from job to job and, in the rough and tumble of daily life, forget what they’ve left behind. Employers don’t try to find missing retirement plan participants, or businesses are bought and sold or restructured so many times that they lose the records. In the haphazard U.S. retirement system, there’s no easy way to make sure your assets follow you throughout your career. Just rolling over an old 401(k) into a new one, or into an individual retirement account (IRA), can mean weeks of hassles.

For example, there’s no central database where you’re likely to find all your old 401(k)s or pensions. No one even keeps data on how much of the nation’s $24 trillion of retirement money might be lost. Terry Dunne, of Millennium Trust Co., which handles 401(k)-to-IRA rollovers, makes an educated guess based on government and industry data that more than 900,000 workers lose track of 401(k)-style, defined-contribution plans each year.

There's a similar problem with traditional, defined-benefit pension plans. About a quarter of retirees who seek help from the Pension Action Center need help finding a traditional pension, said Jeanne Medeiros, the director of the organization, which provides pension counseling in seven states.

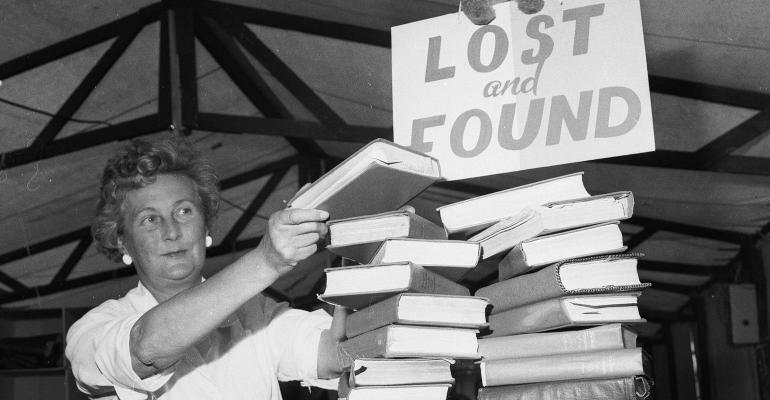

A comprehensive solution may need to wait for Congress. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) in June sponsored a bill with Senator Steve Daines (R- Mont.) to create a “retirement lost-and-found,” a searchable database of abandoned retirement accounts.

In the meantime, the federal agency that insures traditional private-sector pensions is moving to plug one of the gaps. The U.S. Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., or PBGC, already runs a “missing-participants program,” with a searchable database, for the traditional pension plans it takes over. It has handled about 43,000 individual accounts over the past 20 years. Now it's trying to expand the program to 401(k)s and other defined-contribution plans that get shut down.

Under the voluntary service, businesses closing down a 401(k) could transfer stranded accounts to the PBGC or send the agency information on the location of the stranded assets, to be added to a database. The agency estimates that about 24,000 defined-contribution plans are ended each year, mostly at small employers.

“We’ll actually look for the missing participants and pay out the benefits when we find them,” said Tom Reeder, director of the PBGC.

To avoid losing their retirement money, workers with 401(k)s at past jobs should think about rolling them into an IRA or into their current job's 401(k). Rolling over a traditional pension isn't always possible or desirable, so workers need to hold on to records proving their pension eligibility.

Currently, stranded 401(k) accounts are often transferred to private companies, such as Dunne's Millennium Trust, which set up IRAs, notify the account holders, and search for any who can't be found. Millennium, based in Oak Brook, Ill., rolls over about 200,000 accounts a year, said Dunne, the firm's managing director of rollover solutions. It charges rollover IRAs an annual fee of $30, with no other management fees for the default investment option, a money market fund. Using online tools, he said, he can find 85 percent to 90 percent of missing participants. The whole process is "almost always" positive for clients, he said.

But if participants can't be located or don't respond to inquiries, regulations require that their money sit in cash, rather than in riskier investments with the potential for greater growth. Over the years, the value of cash accounts can be eroded by inflation and fees down to almost nothing. When the owner of an IRA turns 70 and a half (an age set in U.S. tax law), many states can even start trying to confiscate abandoned money. The longer your account is lost, Dunne said, “the less likely you’re going to end up with the money.”

The PBGC program, which is expected to be launched in 2018, will be competing against private firms such as Dunne’s. “These companies are not going to go away. They’re still going to have a niche,” said Reeder. He said the PBGC will offer an “attractive option.”

It will keep the cost low, he said—a one-time fee of $35 on accounts of more than $250, zero on accounts of less than that amount—and guarantee that savers receive at least the “federal midterm rate,” an interest rate that varies from month to month and is now above 1 percent. And it will give account holders the option of turning balances above $5,000 into a lifetime income stream similar to a traditional pension.

With some effort, finding people is actually easier than ever. Private search services can cross-reference property records, mobile phone accounts, and other online data to find most people. And employers have a legal obligation to regularly search for missing 401(k) and pension participants.

But Medeiros, of the Pension Action Center, said companies often don't keep good records on pension holders. “Defined-benefit plans have not made much of an effort to find people,” Medeiros said. “They sit back and wait for people to claim their benefits.”

Retirees often need extensive records to prove they’re owed a pension, including decades-old tax returns and plan statements, she said. For 401(k) plans, proving you own an account isn’t the difficult part. It’s remembering to go looking for the $400, or $4,000, you left behind in an old account before it’s eaten up by fees or taken by the state.

Reeder said employers often just “go through the motions” of finding beneficiaries. When so-called missing accounts are transferred to the PBGC, the agency can often find those participants immediately with modern search tools.

“All employers are not as eager to find these people as they should be,” he said.

The U.S. Department of Labor seems to agree. In January it said it was expanding an investigation of large pension plans failing to locate participants.

Then there are the people who don't want to be found. They may be trying to escape creditors or get out of child support obligations. More than a decade ago, the PBGC’s missing-participants program tracked down a participant in the Federal Witness Protection Program, Reeder said. The agency then worked with the authorities to plug that gap.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Peter Jeffrey at [email protected]