(Bloomberg) --You don’t have children to get rich.

From the moment a child arrives, parents pay more—for food, clothes, health care, larger homes, child care and education. The total tab for getting a kid from birth to the 18th birthday is $233,610, according to an annual estimate by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. And that figure doesn’t even include the skyrocketing costs of college tuition.

Parenthood has plenty of non-monetary perks, but the financial effects can last the rest of your life.

More than half of American workers are in danger of retiring without enough money, according to Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research. The center found that children should get at least some of the blame, according to a study released this month.

It may seem obvious that kids make it harder to save. In practice, however, parents can compensate for the extra costs of parenting by spending less on themselves. Parents are often forced to budget carefully—a skill that will pay off long after their children are grown. Some people may even decide to take their careers more seriously after having kids, and studies show that some fathers end up earning more than if they’d remained childless.

The National Retirement Risk Index is the Center’s estimate of how many Americans are in serious danger of not being able to maintain their lifestyles after age 65. The latest NRRI—based on the Federal Reserve’s most recently released Survey of Consumer Finances from 2013—shows 52 percent of U.S. households at risk of falling short of their post-retirement financial needs by 10 percent or more.

To find out how parenting affects retirement savings, the Center re-analyzed the survey data, looking at the correlation between Americans’ financial situations and the number of children they have.

“The bottom line is that households with children would be expected at the end of their work-lives to have less income and lower wealth,” the study’s authors write.

For parents in their thirties, each child is associated with a 3.7 percent drop in income and a 4.5 percent decline in wealth. Older households feel less economic pain: While parents in their fifties have 2.8 percent lower wealth per child, their incomes are barely affected.

A key contributing factor to parents’ financial shortfalls is the so-called motherhood penalty. The typical mother earns $9,400 less per year than the median woman without children, the survey data show, and mothers are also 12 percentage points less likely to be working for pay.

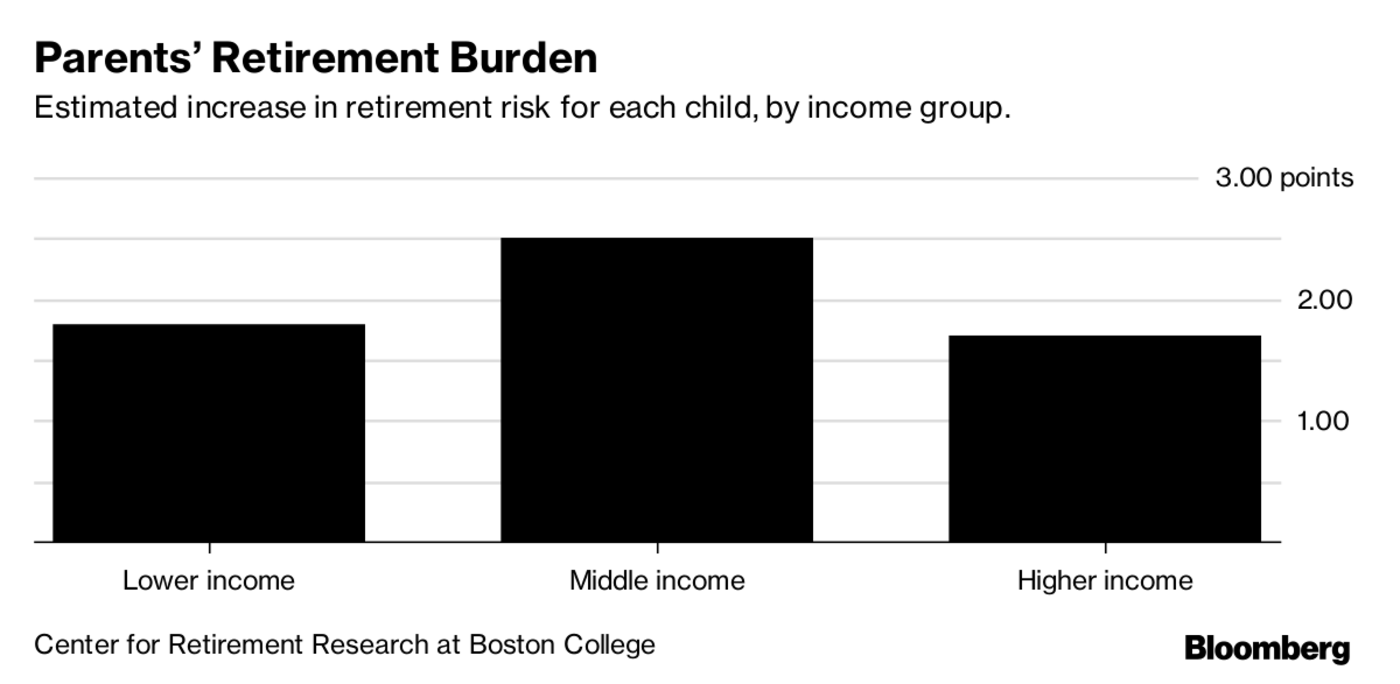

As they approach retirement age, parents can make up some of the lost ground. But they can’t close the gap completely. By age 50 to 59, each child is associated with a 1.9 percentage point rise in a parent’s risk of falling short on the NRRI.

A 2 percentage point jump in retirement risk isn’t catastrophic. Other factors can have a much more profound effect on your likelihood of saving enough. For example, researchers found that access to a traditional pension at work is associated with a 40.5 point drop in retirement risk.

Still, the financial damage of being a parent multiplies the more children you have. And the chances of falling short are higher for the middle class than for other groups.

For the bottom third of workers by income, savings are less important because they can rely on Social Security to meet more of their retirement needs. For the top third of workers, researchers admit that their method may be underestimating the financial hit caused by children. Many well-paid parents appear to have healthy savings, according to the NRRI, but they’re likely to spend huge amounts sending kids to college. “It makes households look more prepared for retirement than they actually are,” the authors write.

Even after children graduate, move out and start their own careers, a parent’s job isn’t necessarily done. According to another Boston College study released last month, many parents continue donating time and money to children well into adulthood.

About a third of parents help adult children with gifts of time, presumably for child care and other chores. They contribute an average of 366 hours a year, researchers found, or 7 hours a week. Eventually, some children return the favor, especially as parents get older and need help. A quarter of parents report receiving the gift of time, an average of 324 hours per year, from their children.

About 31 percent of parents also say they give money to their adult kids, an average of $3,084 in the past year. Money rarely flows in the other direction, however: Only 9 percent of parents report taking money from adult kids in the past year, and the average amount received is just $595.

To contact the author of this story: Ben Steverman in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Josh Petri at [email protected]