Last week I wrote about an SF Fed blog piece on “The Good News on Wage Growth,” which essentially said that wage growth has been low as well-paid baby boomers retire and are replaced with lesser-paid younger people. The upshot is that this is about to change as the boomers taper off, and wages will pick up.

The New York Times took up the subject on Tuesday in their main opinion piece, “Why Is The Fed So Scared of Inflation?” The article went on about the Fed not having such full control over inflation, labor participation and the GOP opposing minimum-wage increases. Standard stuff, but they did point to something worth illustrating: The story of soft wage gains has been under way for a while, longer I think than just the logic that high-wage baby boomers are being replaced by lower-wage younger workers.

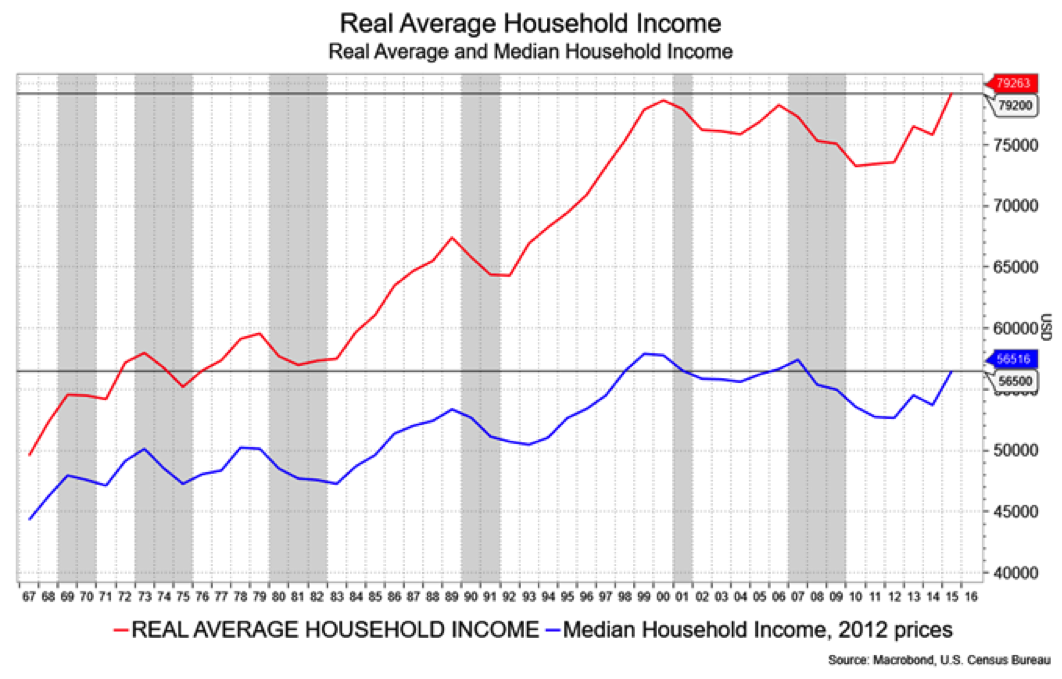

The chart below shows real household income going back to 1967. Note that real HH income has been stagnant since about 1999. In context, median HH income is actually lower, and average is up a paltry $629 over that period, according to Census Bureau data. Now, assuming the first baby boomer was born in 1946, said boomer was only 53 in 1999. If we assume the average retirement age of 65—though that's been rising for boomers—that individual wouldn't have dropped out until 2015, and the bulk of them have years to go before they exit the workforce. And the stats on retirees are scary; low savings, 30 percent of those 65+ still have mortgages and odds are that if you're 65 today you stand a one-quarter chance of living past 90.

The point is that I think the notion that well-paid boomers are leaving work rapidly is hopeful folly. They're working longer and are more flexible in their work habits. In other words, they'll take less money in exchange for health care and flextime. The problem with low wage gains is about skills, drug tests and increasing automation, not too many highly paid old people crowding others out.

While I'm at it, let me show another perspective on incomes. This chart shows wages as a percent of total compensation in a steady decline. That means that benefits are taking up a greater share. In other words, even as boomers retire, it's not clear that wages will go up unless benefits stabilize or shrink. Do you see medical costs flattening out?

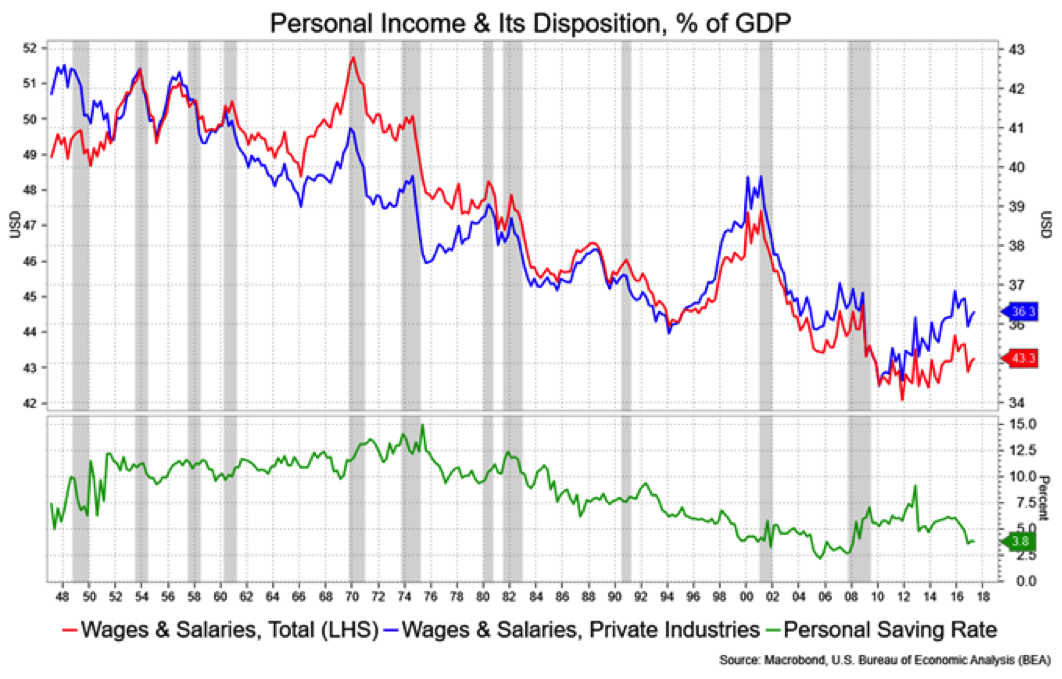

This final chart looks at wages as a percent of GDP being in a long-term decline—well before any impact from retiring baby boomers. While other arenas contributing to GDP are at hand (government comes to mind), what's interesting is that consumption as a percent of GDP is at an all-time high, despite wages as a percentage coming down. We're spending more of our income to consume and saving less, which just brings us back to our original question of whether baby boomers are really so quickly leaving the workforce.

David Ader is chief macro strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.