Damian Williams was laying out the case for a jury he needed to persuade to bring down a hedge-fund high-flyer.

His simple courtroom opening for a seemingly mind-numbing financial fraud: “It’s easy to look like a winner if you can just make up the score.”

And with that, he teed up a trial that would eventually see Stefan Lumiere, a former fund manager at Visium Asset Management, sentenced to 18 months in prison for cheating investors.

That 2017 victory -- clinched after a mere 90 minutes of deliberation by the jury -- is but one of the triumphs that has now vaulted Williams to a pinnacle of American law enforcement as the next head of the feared Southern District of New York.

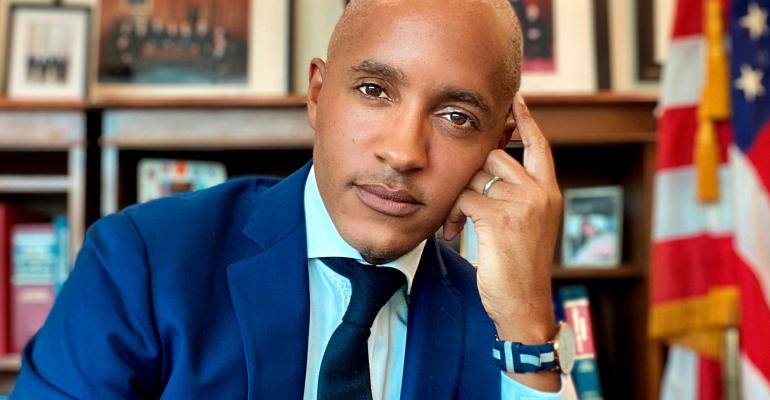

Sworn in Sunday, Williams is taking charge of the office known for being the nation’s most aggressive prosecutor of white-collar crime. He’s assuming the post as the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which sets the tone for the industry’s regulation, tries to revive an aggressive enforcement approach with an ambitious agenda.

Williams is also the first Black person to be in charge of the Southern District in its 232-year history. And, at 41 years old, one of the youngest. He spent the last three years directing the Southern District’s securities and commodities fraud task force.

“He’s a person of immense talent and judgment” and beloved within the office, said Geoff Berman, the former U.S. Attorney who promoted Williams from line prosecutor to a leadership role in the office’s securities unit.

The office, often called the “Sovereign District of New York” for its streak of independence, is known for policing Wall Street and prosecuting many high-profile cases involving terrorism, organized crime and public corruption.

Among the current caseload Williams will be responsible for are the ongoing investigation of former New York Mayor and Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani, the prosecution of Ghislaine Maxwell on sex-trafficking charges and fraud allegations against Nikola Corp. founder Trevor Milton.

Setting Priorities

He takes over at a time of rising violent crime in New York and with relations between law enforcement and minority communities at a nadir. The office has also been accused of withholding evidence from defense lawyers -- earlier this year, a federal judge asked the Justice Department to investigate prosecutors for their actions in a case involving an Iranian businessman.

Since being nominated in August by President Joe Biden, Williams has been consulting with some former U.S. attorneys and senior officials in the office about setting priorities during his tenure, according to colleagues and friends. He was confirmed by the U.S. Senate last week and sworn in during a private ceremony Sunday.

Through a spokesman, Williams declined to comment for this story, and there were no public hearings on his nomination. But some of the people he’s had conversations with say the challenges Williams faces will touch on all aspects of the office’s mandate to prosecute federal crimes.

During President Donald Trump’s administration, prosecutions of financial and securities crimes plummeted to multi-decade lows, prompting some calls for more robust enforcement under Biden. Many of those cases usually start with the SEC, which has signaled an aggressive agenda for policing Wall Street that would involve partnering with prosecutors.

Beyond Wall Street

Gary Gensler, the SEC’s new chairman, told Congress earlier this year that cryptocurrency markets, accounting practices, special-purpose acquisition companies and insider trading by corporate executives are ripe for abuse and greater enforcement.

Wall Street crimes won’t be the only focus for Williams.

The country is seeing a surge in domestic terrorism, such as the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol and the alleged plot to kidnap Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. And there’s been more international cybercrime and ransomware attacks, and the potential for new risks from international terrorism with the Taliban again in control of Afghanistan.

“He is very much thinking about the other units -- not just securities, and not just the criminal division,” said Andrea Griswold, a longtime friend and colleague who has been co-chief of the securities unit with Williams. “He really has taken the time to be thinking about the office’s entire platform.”

Williams is the rare U.S. attorney with a close-up view of how criminal cases impact defendants and those around them, including his own family. In 2012, his father, Andre Williams, an obstetrician-gynecologist, was charged in Georgia with Medicaid fraud for improper billing of more than $200,000 in elective abortion procedures, court records show. He pleaded guilty, got 10 years of probation and was ordered to repay $215,000 to the state.

Mending Fences

Rebuilding morale in the Southern District may also be an important task for Williams, who joined the U.S. attorney’s office in 2012. The office’s reputation for independence took a hit during the Trump years, which included the unceremonious firings of two U.S. Attorneys, Berman and Preet Bharara, and the pardoning of defendants prosecuted by the office, including former Trump political strategist Steve Bannon.

And Williams may need to mend fences with judges. There have been multiple recent instances when prosecutors were found to have withheld important evidence from defense lawyers.

Williams had his own difficult encounter with a judge. He was the lead prosecutor in the 2015 case against entrepreneur Kaleil Tuzman, who was accused of accounting fraud and stock manipulation. Tuzman was arrested in Colombia, where he was held in prison awaiting extradition to the U.S. He was sexually assaulted at knifepoint by four inmates and was targeted for extortion by guards.

Tuzman accused prosecutors of failing to do enough to protect him. A day after a U.S. judge questioned Williams about what the government had done to ensure his safety and why it couldn’t do more, Tuzman was moved to a safer lockup.

Tuzman was later convicted on all counts at trial and faced as long as 22 years in prison. But when it came time for sentencing, the judge imposed no prison time, citing government lapses.

“The government had a moral obligation to do everything in its power to ensure his safety after the danger he was in was brought to the government’s attention,” U.S. District Judge Paul Gardephe said. “The government did not meet its obligation.”

Diaper Delivery

Williams was born in Brooklyn to parents who immigrated from Jamaica. He attended Harvard University, where he met Natalie Portman and struck up such a close friendship with the actress that she later attended his wedding. He got his law degree from Yale University and clerked for then-appeals court judge Merrick Garland, who is now attorney general, as well as Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens.

Williams has two children with his wife, Jennifer Wynn, who worked on education policy at the Obama Foundation. Griswold said Williams is “a co-equal with his wife.”

Their relationship demonstrates “that you can be absolutely excellent and be a good leader and have dinner with your family,” Griswold said. For new prosecutors joining the office, “to see that kind of leadership will be phenomenal,” she said. “He’s had diapers delivered to the office.”

With Williams’s ascension, all of New York’s leading law enforcement offices -- including the U.S. Attorneys for both the Southern and Eastern districts, the state attorney general, and the Manhattan district attorney -- are poised to be held by Black officials. (Alvin Bragg, the Democratic nominee for D.A., is expected to win next month’s election.)

Williams “has a deep desire to give back to the African-American community and a deep sense of social justice issues,” said Ted Wells, a top white-collar defense lawyer at Paul Weiss Rifkind Wharton & Garrison, who became a mentor to Williams when he was a young associate at the firm. “He hopefully will be able to advance and improve the relationship between the law enforcement community and the African-American community, because he’s part of both.”

Williams is incisive, precise and respected by colleagues, according to friends, associates and defense lawyers. They say he’s a keen investigator with an understated disposition that belies an aggressive but fair approach to pursuing cases, and that he routinely maps out strategy several steps ahead.

When building a case and vetting witnesses, Williams is “like a surgeon in those rooms, in terms of his questioning and his ability to smoke out falsehoods,” said Mike Ferrara, a former colleague at the Southern District and now in private practice at Kaplan Hecker & Fink. “He would set himself apart from other prosecutors in terms of preparation.”

‘Hard but Fair’

Among the major prosecutions Williams handled was the insider-trading case against former New York congressman Christopher Collins, who pleaded guilty but was later pardoned by Donald Trump. Williams also led a team that charged David Blaszczak, a Washington, D.C., political intelligence consultant who sold non-public information about Medicare and Medicaid coverage and reimbursement decisions to hedge funds. Blaszczak and three others were convicted.

When New York state Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver’s conviction on a corruption charge was overturned on appeal, Williams led the team that handled his second trial. Silver was convicted again and sentenced to seven years in prison.

One of Williams’s early assignments during his time at Paul Weiss was to help his mentor Wells represent David A. Paterson Jr., New York’s first Black governor, who was under investigation by the state for allegedly accepting improper gratuities. Wells said Williams did much of the legwork for the investigation and took the lead on verbally briefing the governor, who is legally blind and struggled with reading dense, lengthy legal documents. No charges were ultimately brought.

Later, Wells and Williams would find themselves on opposite sides. The young prosecutor led an investigation of whether a major corporation violated securities laws. Wells represented the company.

“I found him to be aggressive, imaginative, hard, but fair,” Wells said.