By Prashant Gopal

(Bloomberg) --On a chilly December afternoon in Atlanta, a judge told Reiton Allen that he had seven days to leave his house or the marshals would kick his belongings to the curb. In the packed courtroom, the truck driver, his beard flecked with gray, stood up, cast his eyes downward and clutched his black baseball cap.

The 44-year-old father of two had rented a single-family house from a company called HavenBrook Homes, which is controlled by one of the world’s biggest money managers, Pacific Investment Management Co. Here in Fulton County, Georgia, such large institutional investors are up to twice as likely to file eviction notices as smaller owners, according to a new Atlanta Federal Reserve study.

“I’ve never been displaced like this,” said Allen, who said he fell behind because of unexpected childcare expenses as his rent rose above $900 a month. “I need to go home and regroup.”

Hedge funds, large investment firms and private equity companies helped the U.S. housing market recover after the crash in 2008 by turning empty foreclosures from Atlanta to Las Vegas into occupied rentals.

Now among America’s biggest landlords, some of these companies are leaving tenants like Allen in the cold. In a business long dominated by mom-and-pop landlords, large-scale investors are shifting collections conversations from front stoops to call centers and courtrooms as they try to maximize profits.

“My hope was that these private equity firms would provide a new kind of rental housing for people who couldn’t -- or didn’t want to -- buy during the housing recovery,” said Elora Raymond, the report’s lead author. “Instead, it seems like they’re contributing to housing instability in Atlanta, and possibly other places.”

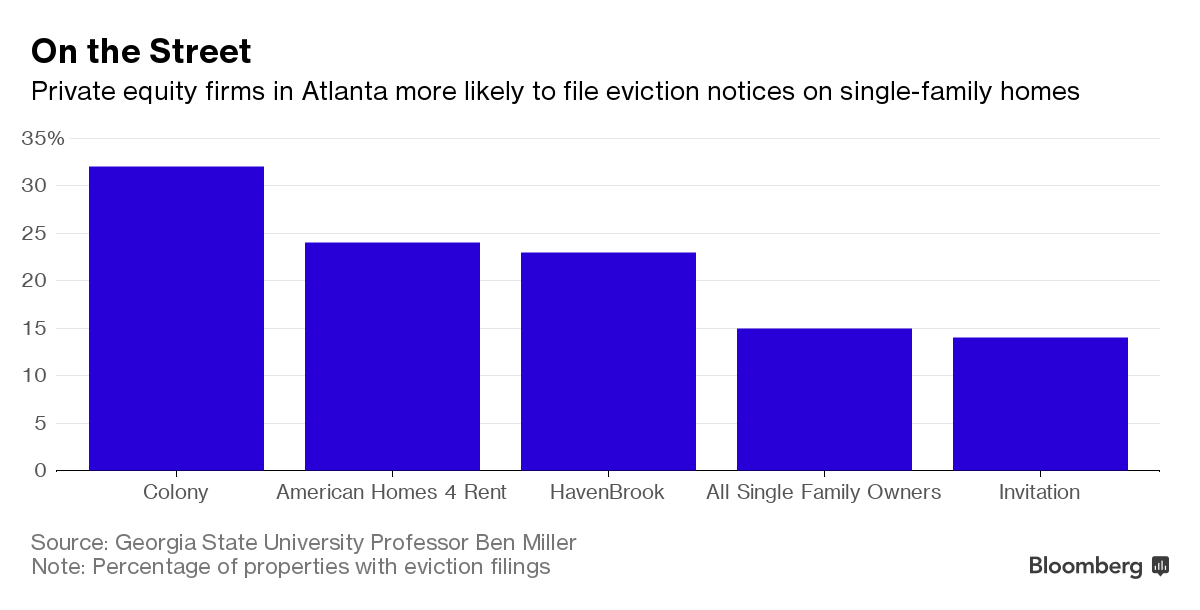

American Homes 4 Rent, one of the nation’s largest operators, and HavenBrook filed eviction notices at a quarter of its houses, compared with an average 15 percent for all single-family home landlords, according to Ben Miller, a Georgia State University professor and co-author of the report. HavenBrook -- owned by Allianz SE’s Newport Beach, California-based Pimco -- and American Homes 4 Rent, based in Agoura Hills, California, declined to comment.

Colony Starwood Homes initiated proceedings on a third of its properties, the most of any large real estate firm. Tom Barrack, chairman of U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s inauguration committee, and the company he founded, Colony Capital, are the largest shareholders of Colony Starwood, which declined to comment.

Diane Tomb, executive director of the National Rental Home Council, which represents institutional landlords, said her members offer flexible payment plans to residents who fall behind. The cost of eviction makes it “the last option,” Tomb said. The Fed examined notices, rather than completed evictions, which are rarer, she said.

“We’re in the business to house families -- and no one wants to see people displaced,” Tomb said.

According to a report last year from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, a record 21.3 million renters spent more than a third of their income on housing costs in 2014, while 11.4 million spent more than half. With credit tightening, the homeownership rate has fallen close to a 51-year low.

In January 2012, then-Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke encouraged investors to use their cash to stabilize the housing market and rehabilitate the vacant single-family houses that damage neighborhoods and property values.

Now, the Atlanta Fed’s own research suggests that the eviction practices of big landlords may also be destabilizing. An eviction notice can ruin a family’s credit and make it more difficult to rent elsewhere or qualify for public assistance.

Collection Strategy?

In Atlanta, evictions are much easier on landlords. They are cheap: about $85 in court fees and another $20 to have the tenant ejected, according to Michael Lucas, a co-author of the report and deputy director of the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation. With few of the tenant protections of places like New York, a family can find itself homeless in less than a month.

In interviews and court filings, renters and housing advocates said that some investment firms are impersonal and unresponsive, slow to make necessary repairs and quick to evict tenants who withhold rent because of complaints about maintenance. The researchers said some landlords use an eviction notice as a “routine rent-collection strategy.”

Aaron Kuney, HavenBrook’s former executive director of acquisitions, said the companies would rather keep their existing tenants as long as possible to avoid turnover costs.

But “they want to get them out quickly if they can’t pay,” said Kuney, now chief executive officer of Piedmont Asset Management, a private equity landlord in Atlanta. “Finding people these days to rent your homes is not a problem.”

Poor Neighborhoods

The Atlanta Fed research, based on 2015 court records, marks an early look at Wall Street’s role in evictions since investment firms snapped up hundreds of thousands of homes in hard-hit markets across the U.S.

Researchers found that evictions for all kinds of landlords are concentrated in poor, mostly black neighborhoods southwest of the city. But the study found that the big investors evicted at higher rates even after accounting for the demographics of the community where homes were situated.

Tomb, of the National Rental Home Council, said institutional investors at times buy large blocks of homes from other landlords and inherit tenants who can’t afford to pay rent. They also buy foreclosed homes whose occupants may refuse to sign leases or leave.

Those cases make the eviction rates appear higher than for smaller landlords, according to Tomb, whose group represents Colony Starwood, American Homes 4 Rent and Invitation Homes. The largest firms send notices at rates similar to apartment buildings, which house the majority of Atlanta renters.

Staying Home

Not all investment firms file evictions at higher rates. Invitation Homes, a unit of private equity giant Blackstone Group LP that is planning an initial public offering this year, sent notices on 14 percent of homes, about the same as smaller landlords, records show. In Fulton County, Invitation Homes works with residents to resolve 85 percent of cases, and less than 4 percent result in forced departures, according to spokeswoman Claire Parker.

The Fed research doesn’t say why many institutional investors evict at higher rates. It could be because their size enables them to negotiate less expensive legal rates and replace renters more quickly than mom-and-pop operators.

“Lots of small landlords, when they have good tenants who don’t cause trouble, they’ll work with someone who has lost a job or can’t pay for the short term,” said David Reiss, a Brooklyn Law School professor who specializes in residential real estate.

After a two-year acquisition frenzy that ended in 2014, companies shifted their focus to reining in expenses related to maintaining and managing thousands of homes spread out across many states. In November, Colony Starwood told analysts it had reduced property-management costs by 25 percent in the third quarter from a year earlier. For example, about a quarter of the 26,000 service calls received at the company’s national service-dispatch center were resolved using troubleshooting or “robust self-help tools.”

Broken Pipe

Juliana Spence tangled with Colony over the cost of maintaining her house in DeKalb County, Georgia, where she also operated a small daycare center. A broken pipe under her dishwasher pushed her monthly water charge over $400, she said, and a faulty air-conditioner resulted in an $800 electric bill.

The company gave her an $1,800 credit, Spence said, but she still fell behind on her rent. Colony evicted her last year. It made “Band-Aid” repairs, leaving underlying problems to fester, she said. Colony declined to discuss individual customers.

“They do makeup work,” said Spence, 41, who has five kids. “They made the walls look nice. They put some new appliances in. But the gut of the house is the same.”

In Fulton County, Georgia, the focus of the Fed’s study, evictions are so common that tenants arrive every Tuesday and Thursday to plead their cases. Few have lawyers. They file into the courtroom, many holding their children’s hands as they wait to hear from a judge.

Mass Misery

The unluckiest show up for late afternoon sessions. Legal-aid lawyers call it “the calendar of death.” These renters have run out of options. A judge tells them, en masse, they will have seven days to leave their homes.

On a December weekday afternoon, April Brooks tried to work out a deal with Colony Starwood, her landlord. Raising her three young children on her own, she lived in a boxy, brick house on top of a hill, near the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. A toy train and school bus lay on her front stoop.

Brooks took off time from her warehouse job and, in a sweatshirt and dreadlocks, arrived at Fulton County’s Magistrate Court for her mediation session. She didn’t know why Colony wanted her to leave. A Section 8 housing voucher, sent directly to her landlord, paid her $1,000-a-month rent.

Court papers gave a cryptic reason for Brooks’ removal: “Landlord seeks possession. Tenant holdover.”

“This is super hard,” said Brooks, who couldn’t find another landlord willing to accept her housing voucher.

She feared the next stop for her and her three kids: the streets.

To contact the reporter on this story: Prashant Gopal in Boston at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: Daniel Taub at [email protected] ;David Gillen at [email protected] John Hechinger