Back in December, we predicted a divided Congress because the U.S. Senate runoffs in Georgia were going to go the Republicans’ way. This was based on a number of factors including historical turnout, split tickets on Nov. 3 and campaign dollars.

Obviously, we were wrong.

To be fair, we could have never predicted the months-long post-election campaign of former President Donald Trump focused on overturning his loss, instead of shoring up the Senate for Republicans. Many of whom stood by him for four years. That can be called snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

But credit also goes to the Stacey Abrams campaign machine. She pivoted the strategy that nearly got her elected governor of Georgia to the two Senate runoffs and, along the way, convinced previously dispassionate voters that this was their moment. And those voters delivered the Senate to the Democrats.

Now that the Democrats have control of both chambers of Congress and the White House, it begs the question—what comes next? Well, it wouldn’t be a new presidency without endless talk of taxes. So, we’re going to break down what we see as the art of the possible, given competing priorities and how we might get there.

Budget Reconciliation or Reconciling Among Colleagues?

With margins exceedingly tight, there are technically three ways Senate Democrats can pass legislation in the 117th Congress. First, and the least likely, would be eliminating the filibuster, which is a rule that currently prevents the chamber from passing legislation without 60 senators in support. Incoming Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) has expressed a desire to scrap the rule—which only needs 51 senators to change—but he would need his entire caucus on board, and right now, at least Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) is a strong holdout, with other Democrats also expressing hesitations.

Second, and more likely, is the budget reconciliation route, which is commonly used to pass partisan legislation with slim majorities. You may recall the tax bill in 2017 and the Affordable Care Act in 2010 both passed via budget reconciliation. Budget reconciliation is a powerful legislative tool that allows the Senate to pass spending and tax legislation with a simple 51-vote majority, avoiding the filibuster entirely. But, this powerful tool has limitations. For instance, it can be used only once per fiscal year, and each provision must impact revenue (so raise revenue or lose revenue).

Interestingly, should Democrats go the budget reconciliation route, U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) will have a heavy hand in the shaping of that bill as incoming budget chairman. Given his very liberal politics, it’s not a sure bet that a Sanders-influenced bill will be able to win all 50 Democratic votes (with Vice President Kamala Harris giving them 51).

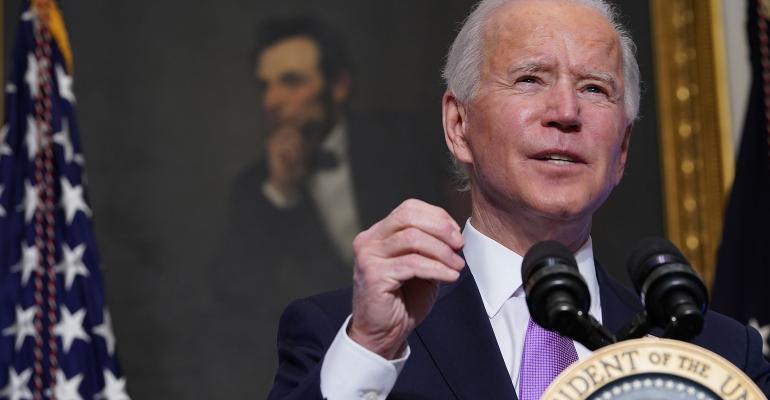

Third, and what many are hoping for, is that lawmakers will find common ground on issues and how to solve them. Democrats will want to quickly pass more COVID-19 relief legislation, likely leaning into the $1.9 trillion bill that President Joe Biden’s team recently put some details around. But to get something close to that, they’ll need at least 10 Republicans on board to prevent a filibuster. Democrats also have many priorities that won’t be able to pass through reconciliation (because of the limitations), like tackling climate change, immigration and terrorism. For all of these priorities, they’ll need to find common ground with Republicans to avoid getting stuck in a filibuster, so eventual legislation could look a lot more moderate than the ideas on which many lawmakers campaigned.

Tax Cuts and Tax Hikes

Now that we’ve laid out the three ways Senate Democrats can move their priorities forward, let’s focus on the priority most likely to impact donors: taxes. Democrats across the country ran on hiking taxes for the wealthy and corporations while providing relief for those toward the bottom of the income scale, and they’ll certainly use the tools at their disposal—likely budget reconciliation—to advance that platform.

In the cuts space, we’re likely to see additional and enhanced tax incentives for middle- and low-income taxpayers. We also expect many Democrats will try to lift the cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction, which was set at $10,000 in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This is, however, a much less attractive tax break because most of the benefits go to the highest earners.

In the tax hikes arena, we expect Democrats to try to raise the corporate rate from 21% to something in the 25% to 30% range, and we expect an increase in the highest individual income rate. Additionally, senators like incoming Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) have been looking to tax investment income at ordinary income rates and do it annually. So, the highest earners can expect a higher tax bill should Democrats be successful.

If you’re not looking forward to those hikes though, we don’t expect them any time soon. Biden’s team is nervous tax increases could stall a robust economic recovery and considerably shorten his administration’s honeymoon period.

So, what does this all mean? More money in government coffers and less money in the wallets of donors to charitable causes. And less money in the wallets of donors means less is given to the charities that are helping alleviate the growing problems that communities are facing in these unprecedented times.

We don’t know exactly when lawmakers will set their sights on these tax changes—they do of course have pressing matters like further COVID-19 relief, confirmations, impeachment and domestic terrorism to deal with first—but we do know that when they get to taxes, there’s the real possibility that donors will have a lot less disposable income to give away.