By Stephen Gandel

(Bloomberg Opinion) --What’s the appropriate board gift for a CEO’s two-year anniversary? If you’re Tim Sloan at Wells Fargo & Co., the correct answer is a short leash.

Sloan took over the CEO role in mid-October 2016, which means the anniversary is this week. At the very least, Sloan badly underestimated the problems facing his bank. But he’s also been slow to address the issues that have come up since he took over, particularly with regulators, and has yet to fully solve them. And while Sloan inherited a tough job, two years in it’s hard to find a single business metric that has improved.

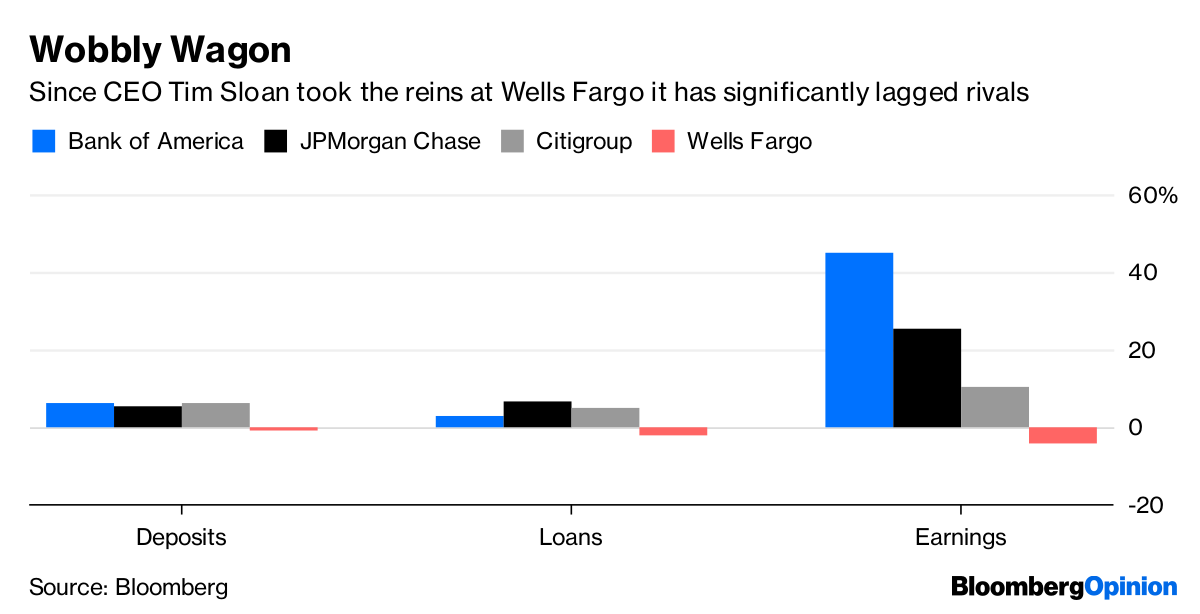

Both loans and deposits are down. Earnings, too, are expected to fall 4 percent this year from the year when Sloan took the job, and that’s including an estimated $1.25 billion boost from this year’s corporate tax cut.

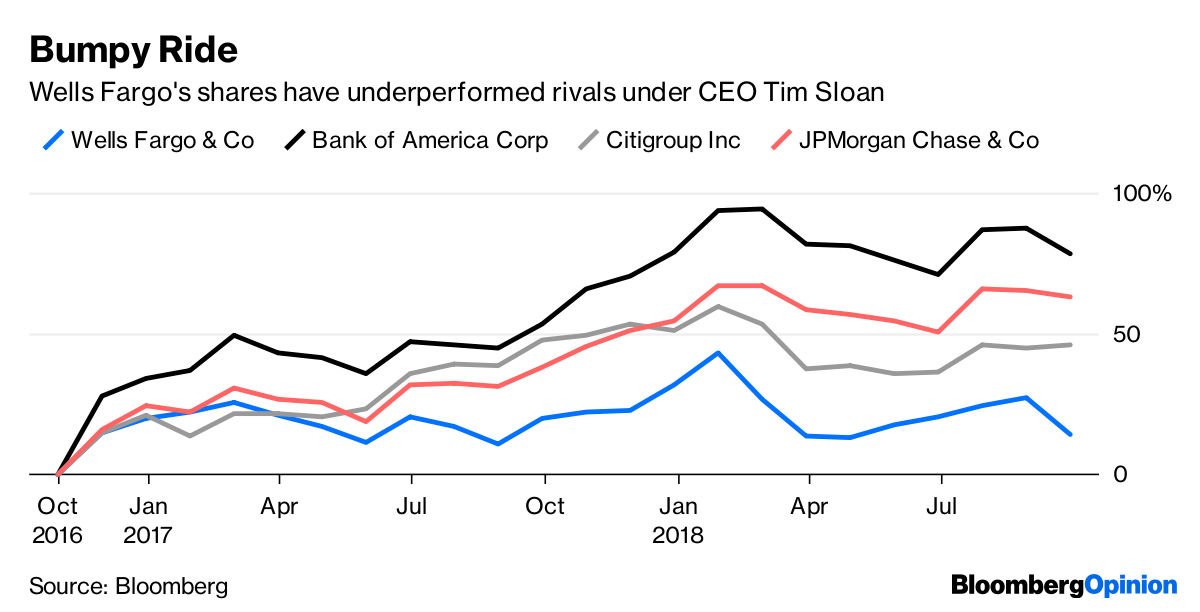

During the same period, the bank’s three main rivals — Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. — have each increased loans and deposits. Earnings at the three banks are up an average of 27 percent. Shares of Wells Fargo — up 22 percent, including dividends, during Sloan’s tenure — have badly trailed rivals, which have returned an average of 72 percent in the same period. (Wells Fargo’s shares were starting at a higher valuation than rivals.) In another sign of Wells Fargo’s troubles, its price-to-book ratio, which has been the highest of the big banks for much of the past two decades, now trails JPMorgan’s.

Perhaps it’s not a surprise that Wells Fargo would trail rivals, given the phony account scandal that swept Sloan into office. But Wells Fargo has also failed to meet its own targets, set well after management was aware of the problems. Earlier this year, Wells Fargo predicted its return on equity would rise as high as 15 percent in 2018. Instead, it is expected to sink to 11.7 percent. Wells Fargo also predicted its revenue would rise this year. Instead, analysts expect the bank’s sales to fall 2 percent.

But Sloan’s most glaring failure has been fumbling the bank’s interactions with regulators. Observers says Sloan in his first year on the job failed to respond to regulators, nor did he take their investigations seriously enough. By mid-2017, Wells Fargo’s top executives had reportedly convinced themselves that they had solved the bank’s regulatory problems. Since then, Wells Fargo has been hit with a consent order from the Federal Reserve that limits how much it can grow, as well as a $1 billion fine from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The Fed, in its consent order, cited Wells Fargo’s failure to correct deficiencies that regulators had previously pointed out to the bank as a reason the Fed went ahead with the consent order.

A Wells Fargo spokesperson called Sloan’s support from the board “unanimous” and unwavering. “In two years as CEO, Tim has driven significant transformational change at Wells Fargo, which is benefiting all stakeholders.” As signs of improvement, the spokesperson pointed to a second-quarter presentation that showed a slight increase in customer accounts in the past year as well as an uptick in debit card transactions, neither of which is surprising in a growing economy.

But the presentation also showed that customer loyalty scores have dropped this year. As for bolstering risk controls, at its May investor day, Wells Fargo published a chart showing that investing in regulatory compliance was one of the bank’s top priorities. But the bar chart was not labeled with numbers or a y-axis. What’s more, it showed that the bank plans to cut its investment in the area in 2018 and 2019. The 2017 bar is the tallest, but Wells Fargo has never disclosed what it invested in its risk management systems in 2016, so it’s impossible to know whether it invested more or less last year. Its financial statements show an $800 million increase in 2017 on “regulatory and compliance related matters,” but that includes spending on legal fees and other professionals.

Sloan has said several times this year that those who think he shouldn’t be CEO know little about either Wells Fargo or what they are talking about.

Sloan himself at times has seemed ill-informed, especially in his many “Mission Accomplished” moments. In July 2016, roughly three months before he got the top job, and as the bank was negotiating a settlement with the CFPB over the phony account scandal, Sloan said in an interview that he didn’t think the bank had a sales problem. In February, Sloan told Bloomberg Businessweek that there was not much left to fix at the bank. And in May, Wells Fargo launched an advertising campaign stating it was a “new day at Wells Fargo.”

Since then, the bank has restructured its wealth-management division amid an investigation into sales practices there. It disclosed that employees in its commercial banking division might have improperly altered client records. The bank fired a dozen employees for falsifying expense reports and is investigating many others. It has also suspended two employees for their role in potentially cheating the federally funded low income housing tax credit program. The Department of Justice is investigating. On Tuesday, Joseph Otting, head of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, said he wasn’t satisfied with Wells Fargo’s response to problems in its auto-lending unit.

As for morale inside Wells Fargo, UBS Global Research recently released a study concluding that the bank’s overall employee satisfaction score had declined significantly in the past three months to the lowest it has been since 2015. The study also found that Sloan’s approval rating among employees was significantly below that of CEOs at rival banks.

It’s fair to ask whether given the scale of its problems, two years is enough time to judge Sloan’s progress. But last week, another giant company, General Electric Co., which arguably has even bigger problems than Wells Fargo, sent its CEO John Flannery packing after just 14 months.

Sloan will soon have 10 more months than that under his belt. It’s time for Wells Fargo’s board and shareholders to demand results.

Stephen Gandel is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering banking and equity markets. He was previously a deputy digital editor for Fortune and an economics blogger at Time. He has also covered finance and the housing market.

To contact the author of this story: Stephen Gandel at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit bloomberg.com/view