by Catherine Bosley (Bloomberg)

When Switzerland pushes the button to send data on offshore bank accounts to foreign tax agencies this fall, it will be doing what was once virtually unthinkable: abandoning the absolute secrecy once afforded to anyone parking their cash in Zurich or Geneva.

The automatic exchange of account information due to take place with other European countries is the last chapter in a saga that began with the arrest of former UBS Group AG banker Bradley Birkenfeld in 2008, cost Swiss banks more than $6 billion in fines, and prompted criminal probes and travel bans for bankers.

Of the more than 80 institutions to wind up in the crosshairs of U.S. authorities – among them UBS, Credit Suisse Group AG, and Julius Baer Group Ltd. – Basler Kantonalbank and Zuercher Kantonalbank, are the latest to settle with the Department of Justice. Basler will pay $60.4 million, while Zuercher agreed to pay $98.5 million and both publicly owned banks admitted to helping clients conceal income and assets from the U.S. government. Pictet and HSBC Holdings Plc’s Swiss unit are still waiting to settle.

While banks have stopped accepting untaxed assets, the “economic war,” as UBS CEO Sergio Ermotti referred to the crackdown, ultimately didn’t end Switzerland’s appeal as a place for the world’s wealthy to park their money. It also didn’t sink the economy into recession, as a 2012 KOF Economic Institute report warned might happen.

“Supposedly” the end of banking secrecy was going to be “the death knell for Swiss banks -- they would’ve lost their competitive advantage and gone out of business,” said Mark T. Williams of Boston University. “Ten years later, that is clearly not what happened,” he added. “I think Switzerland continues to be very strong in regards to asset management. As a tax haven, not so much.’’

The secrecy statute, enacted in 1934, clearly helped the financial industry attract foreign money. The law stipulates that any banker found to intentionally disclose “secrets” obtained as part of their role could be jailed for up to three years or fined.

The crackdown started in 2008. Led by the U.S. and soon vigorously pursued by Germany, France, Italy and others, it put the spotlight on how the rich hid money from the tax man with the help of Swiss banks, damaging the sector’s reputation.

Travel Ban

For years, some bankers avoided foreign travel for fear they might get arrested, as was former UBS wealth management head Raoul Weil, picked up in Italy, extradited to the U.S. and subsequently cleared by a Florida jury. After ZKB, the biggest state-backed bank, settled with the DoJ earlier this month, it lifted a ban on some employees’ personal travel to the country.

“Some bankers were scared. If you had been related to wealth management with U.S. clients anywhere in the world, there was a moment where you decided to no longer travel,” said Matthias Schulthess, a partner at Schulthess Zimmermann Executive Search. Weil’s acquittal was a “relief for many people, especially on the senior end.”

Parliament in Bern allowed the handing over client data to Washington in 2010 to shield UBS, which had to be saved two years before with a $59.2 billion government rescue package due to sub prime mortgage writedowns. Financial institutions began regularly sending account details to the U.S. in 2015. Switzerland will now also send details on account holders to countries including Canada, Japan and the European Union’s 28 member states.

Wealth Winner

Today, Switzerland still is world’s preeminent offshore wealth management hub, as reports by both Deloitte and Boston Consulting Group this year found. BCG determined it had $2.3 trillion of such assets, twice the sum held by runner up Hong Kong. That is in part because, as central bank chief Thomas Jordan noted in 2014, political and financial stability, a well-functioning judiciary, low inflation, and the franc’s status as a haven contributed to Switzerland’s appeal.

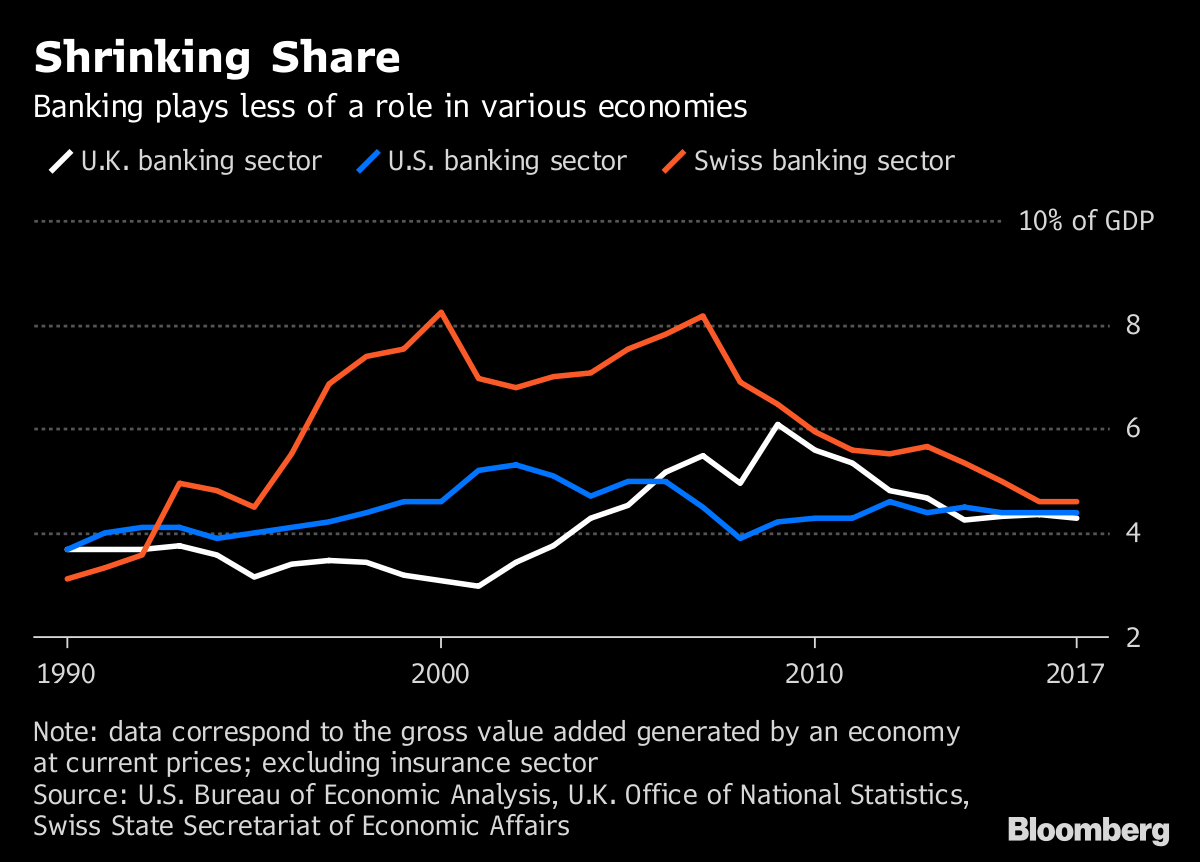

While following the 2008 global financial meltdown banking shrank in relation to the overall size of the Swiss economy, in the U.S. and the U.K. the sector also suffered a decline.

‘Big Blow’

The end of banking secrecy was a “big blow” to Swiss finance, especially the smaller banks, which got saddled with high compliance costs, said Nuno Fernandes, dean of Católica Lisbon School of Business and Economics. “But it’s also true that many people expected it to be worse, and there was no disappearance of the sector.’’

The number of banks in Switzerland dropped to 253 as of last December, down from more than 300 before the financial crisis, according to central bank data. While most are closely held, the two biggest are listed on the stock exchange.

Profits at Credit Suisse and UBS have been less than half of pre-crisis highs in recent years, but have also become more predictable as their focus shifted from high-risk investment banking to a tamer version of wealth management. Clients whose principle concern was shielding assets from the government have become more price sensitive now that their money is declared.

Still, the global stock market rally has been responsible for about 90 percent of the private banking sector’s growth in assets under management last year, according to KPMG. Net new money amounted to only 21 billion francs in 2017, and about half the banks suffered net outflows during the period.

Having lost their “competitive advantage” based on secrecy, banks in Switzerland have “been quite good” at weathering the crisis, said Sebastien Mena, senior lecturer in management at Cass Business School in London. “Of course they had to pay huge fines.”