Adam Nugent’s Foresight Wealth Management is the type of advisory business private equity firms seem to be interested in owning. It’s a fast-growing firm and built with scalability in mind.

In fact, four private equity firms have expressed an interest in the Salt Lake City-based registered investment advisor that oversees more than $450 million in client assets, according to Nugent, the founder and CEO. But a deal hasn’t happened yet.

”When it finally came down to the signing-off on the numbers, the terms changed and it didn’t seem as advantageous,” Nugent, who declined to name the firms, said. “I think they just got greedy.”

Nugent said the sticking point for him so far was over where the line was drawn in terms of equity. “But for the right deal, I would do it in a heartbeat. I love the concept and the idea, I think it’s a matter of terms,” he said. “The math behind it is phenomenal,” Nugent said about the investment returns on wealth management businesses. “I don’t think there is a greater investment than purchasing other investment advisor firms.”

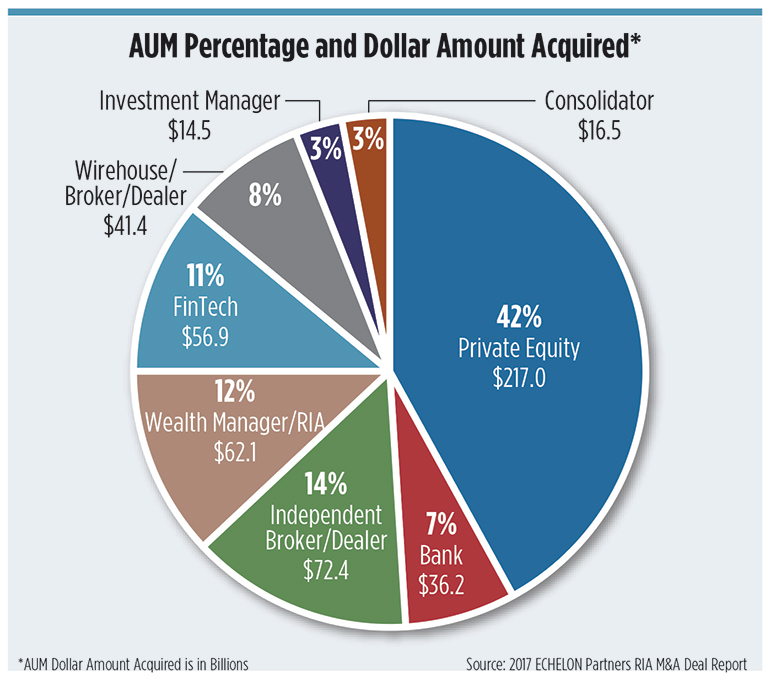

Private outside investors have long been intrigued by wealth management companies, but that interest is ramping up and actual deals are on the uptick, according to industry observers.

As traditional lenders have been reluctant to bring liquidity to the wealth management market with relationship-based businesses having little collateral to borrow against, private equity has stepped into the breach, to fund growing companies and accelerate deals across the landscape.

Last month, Hellman & Friedman agreed to buy Financial Engines, the largest, publicly traded RIA in the U.S., for $3.02 billion. At $45 per share, the all-cash deal closed at a 32 percent premium above Financial Engines’ closing share price of $33.95 on April 27. The sale price was 41 percent above the trailing 90-day, volume-weighted average stock price.

In October, Thomas H. Lee Partners bought a stake in HighTower Advisors, the Chicago-based RIA with $50 billion in assets, to “recapitalize” the private equity firm, and said it would commit an additional $100 million in new capital to accelerate its growth.

In another headline deal between private equity and wealth management, KKR and Stone Point Capital bought roughly a 70 percent stake in Focus Financial Partners in April of 2017, which valued the wealth manager at $2 billion. Focus Financial Partners has since filed for an initial public offering on May 24.

Each deal had its own nuances, but all were a form of consolidation. HighTower Advisors, essentially, rents a platform to RIAs. Focus Financial Partners acquires an equity stake in its RIA partners and Hellman & Friedman agreed to buy Financial Engines outright and intends to merge it with its previously acquired Edelman Financial Services, the mass affluent-facing RIA giant founded by Ric Edelman.

“We’re seeing private equity firms look at the space from every angle,” Shirl Penney, the CEO of Dynasty Financial Partners, said. Although, he stressed a need for wealth managers to understand private equity partners. Smart money is available but it's not free or without risk.

Often private equity firms invest with a mandate to keep operating margins growing ever-larger as they eye a relatively short- to mid-term window towards a liquidity event, such as an IPO or a sale to other investors. That could potentially put PE investors at odds with company managers, particularly owners with longer-term goals for their companies.

Penney said any wealth manager considering a private equity deal needs to hire an investment bank. Private equity investors have their own language and a novice just getting up to speed on hurdle rates or vintage years shouldn’t be weighing those details on their own—they’re going up against professionals with deep expertise. “Just because they are a high quality financial advisor doesn’t mean they are going to be a great CEO or that they understand advanced financial engineering,” Penney said.

Owners of a suddenly slowing or underperforming business–be it related to a market pullback or for any other reason–might find themselves in conflict with the priorities of their new equity partners. Depending on a deal's payment-in-kind, or "PIK," stipulations, if a wealth manager's growth isn't outpacing the debt it's taking on, a private equity owner might have a right to more equity. A lack of financial performance could also entitle a private equity owner more control over time, Penney said.

"As general rule PE firms, as professional investors, will be more structured than other types of investors. For some, the forced professionalization may be welcomed, but other entrepreneurs may not like feeling more like being an employee with tight controls," he said.

Wealth managers also tend to lump all private equity firms into one group and are unaware of the subcategories or specialities of individual firms, according to David DeVoe, the founder and managing director of DeVoe & Company, a consultant to wealth managers. Some private equity firms have more expertise leveraging debt, taking a company public or private, or might function more similarly to a venture capital firm, and it's important wealth management principals be aware of the type of investors they are partnering with to make sure there’s an operational and strategic fit.

“PE can add value and power but these are individuals that have gone through a myriad of these transactions and structured their agreements with a bias toward them and their investors,” DeVoe said. “They aren’t there to gouge anyone, but you want to make sure the structure is appropriately fair to all parties.”

That dynamic seems less prominent in the wealth management space, says Lee Equity Partner Daniel Rodriquez, because it’s not purely a consolidation story that’s attracting the capital. He said the size and growth rate of the industry (already at $55 billion globally and expected to grow to just under $70 billion by 2021, according to Ernst & Young’s 2018 Global Wealth Model) was the main draw.

He says his firm, with investments in Edelman Financial Group and Atria Wealth Solutions, is looking for long-term relationships with managers.

Part of the attraction is also the industry’s transition to fee-based advice. That’s led to more consistent revenue and forward-looking business plans, and in many cases margins that are “still quite attractive,” says Anna Zakrzewski, partner and managing director at the Boston Consulting Group.

For RIAs, the deals with private equity investors solves a problem many have of accelerating a growth plan that can only be accomplished successfully with an infusion of capital. Their clients are expecting better technology and digital capabilities akin to those found in other areas of their lives, including large retail banks—something most firms need much greater scale to develop and provide.

“If you’re not on the good side of scale, the market is going to pull away from you very fast because it’s going to become obvious in the type of digital experience that a client has,” said Ron Carson, founder and CEO of the Carson Group. It was his commitment to investing in technology upgrades for his clients that led him to make a deal with Long Ridge Equity Partners. In 2016, the firm invested $35 million in the Carson Group. Carson said it was more than just money that sold him on the deal. He added Long Ridge co-founder and managing director Jim Brown and partner Kevin Bhatt to his executive board.

“We didn’t do it for the money, we did it for their knowledge,” Carson said. “We had no debt when we brought them on and we continue to have no debt.”

The paradox of private equity in wealth management is that those firms attracting the most interest aren’t usually the most in immediate need. In fact, those firms that aren’t growing or don’t have a plan in place to scale effectively find little interest from the investors.

“[Private equity firms] don’t want to spend time turning a firm around,” Carson said. “They want to pour fuel on a fire, not rehab one.”

Still, Jason Barg, a partner at Lovell Minnick Partners, which has investments in Mercer, Lincoln Investments and HD Vest, offered one note of caution: While the markets were going well, it’s difficult to see the potential downside of private equity owners, he said. That is one reason wealth managers need to make sure they’re taking on investors with some experience in the industry, and not those that are just a “ tourist” in the sector.

“It’s easy to be a good partner when things are going well,” he said. But consider an unforeseen event or downturn in the markets that impacts a wealth management firm’s financial standing; if an advisor has to choose between satisfying the demands of his private equity owners or the needs of his clients, which stakeholder is most likely to win out?