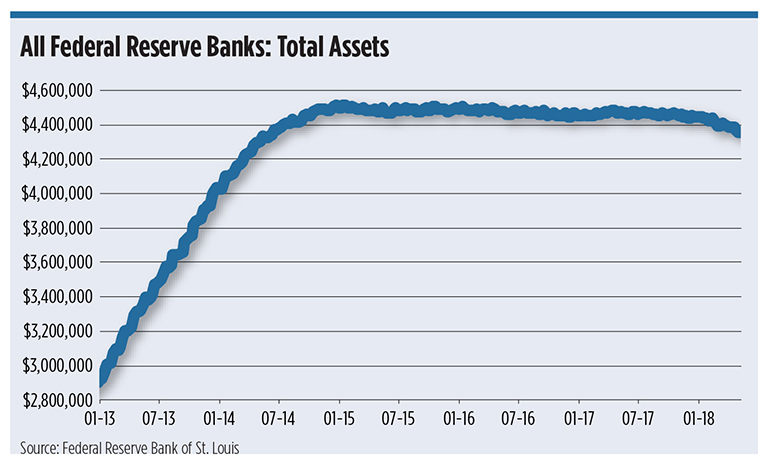

The Federal Reserve’s process of winding down its massive $4.5 trillion balance sheet started last October and is moving along quietly in the background in the midst of a calibrated series of modest rate hikes. The schedule that the Fed announced last September about this process is quite elaborate, involving specifics regarding the monthly runoff of Treasurys, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities with the maximum amount the runoffs will be increased in steps of three-month intervals during the first year of the process until they reach a combined $50 billion per month. So far, the Fed’s portfolio has only shrunk by a rather inconsequential $120 billion or so (graph below), but the pace of reduction in its securities holdings is on track to pick up pace by the end of the year.

The reason the entire project has attracted minimal attention in the bond market over the last seven and a half months is a testament to the solid structure and predictability of the process that Yellen’s Fed left behind. This allowed the process to unfold smoothly, away from the financial market’s otherwise ever-vigilant eyes. Markets are focused primarily on the parallel track of the normalization of monetary policy: the series of rate increases that the Fed is anticipated to put in place over the balance of the year and into 2019.

It is precisely the result of how orderly the normalization of the central bank’s balance sheet is playing out that a seemingly hypothetical but very pertinent question has not yet been raised: What can throw a monkey wrench into the process and what would the implications be for financial markets?

The answer is a significant, but asymmetrical, change in the pace of economic activity and its prospects over the next several quarters.

The Fed’s desire is clearly to use the federal funds rate as the frontline tool to conduct monetary policy in the periods ahead. The winding down of its balance sheet is to play more of a parallel, secondary role in the background. This means that substantial changes in the economic outlook would most likely alter, in either direction, the pace of interest rate increases rather than involve a quick change in the scheduled pace at which securities are running off from its portfolio.

However, here’s where the concept of asymmetry comes into play and why it merits some attention.

An unexpected strengthening of economic activity that heightens anxiety over its implied inflation risks would lead the Fed to pick up the pace of rate hikes, but most likely would not trigger an acceleration in winding down the portfolio. The latter is viewed more as a long-term, structural process that requires a higher threshold to be thrown off course.

If, however, economic activity slows over a string of quarters going into 2019 as a result of a confluence of factors, such as further rise in oil prices denting consumer spending, the vaguely anticipated tax cut-related capital spending never materializing, or any other exogenous adverse development, then the Fed’s response is likely to be more forceful in an attempt to cushion the downside risks for the economy.

Under that scenario, the Fed would not only suspend the rate increases but would almost certainly do the same with the runoff of securities in its portfolio, as continuing with the process would represent a tightening of financial market conditions in an environment where the economy is in danger. In other words, when the economy is perceived as running into unanticipated headwinds that threaten the longevity of the business cycle, the Fed is more likely to pull out all stops to contain the situation in a bid to achieve that much talked about, but rarely realized, “soft landing.”

So, what would be the implications for bonds and equities if a dynamic developed that forces the Fed to suspend its portfolio normalization process? The strongly intuitive answer is that it would trigger a major rally in Treasurys, with the 10-year yield eyeing the 2 to 2.5 percent range, or possibly lower, and cause a sharp pullback in equities on the order of at least 10 percent.

The positive response of Treasurys would be fueled not only by the prospects of an alarming cooling in economic activity but also by the more technical aspect of a decline in the supply of securities hitting the market that was generated by the previous runoff of the portfolio.

As for the reaction of equities, history offers an unassailable pattern of what happens to that asset class when faced with the prospect of an economic expansion facing an existential threat.

Following a long career as a professional economist in the financial markets, Anthony Karydakis currently teaches at the Economics Department of NYU’s Stern Graduate School of Business. He holds a doctorate from The Sorbonne in Paris.