The New York Times offered a story on Tuesday, “Come the Recession, Don’t Count on That Safety Net.” Guess what it’s about?

It starts by wondering “what will President Trump’s first recession look like?” It’s a fair question, I suppose, though I’d rather they asked, or added, “what will cause Trump’s first recession?”

Anyway, what the article takes an awful long time getting around to—after twice saying the question they pose isn’t so outlandish or premature and that the recent volatility shows how jittery people are AND pointing out that the tax plan and increased spending “boxed” the economy into a corner against the chance for stimulus in case we have a recession—is this: It’s going to be hard on people.

First, the article points out that we’ve exhausted a fiscal response unless we plunge into even deeper deficits, which is always a possibility. Secondly, it alludes to the Fed being potentially less sympathetic, given the deficit/stimuli just installed. Thirdly, it cites a study that the safety net has shifted to in-work families from out-of-work families. “Benefits that require recipients to hold a job become worthless when there’s no work to be had,” according to the article.

I’m not sure there’s much more to say on that matter other than, yeah, well. Fiscal options have, indeed, been closed off, irresponsibly if you ask me, but that doesn’t mean it can’t get worse in a recession as tax revenues fall off, which they will. Prudent tradition has it that a country is supposed to narrow or eliminate budget deficits in a growth phase and NOT do what has happened since the Bush era.

Further, though the article doesn’t touch on it, is Fed policy. Would, say, a cut in rates between 2.5 and 3 percent to 0 percent again have much impact? Would they buy securities again? And did that do anything in the first place, other than to boost risk assets and “encourage” policymakers in Congress to spend at Fed-influenced low interest rates? I can imagine the next recession being relatively shallow but, like the expansion, longer than normal.

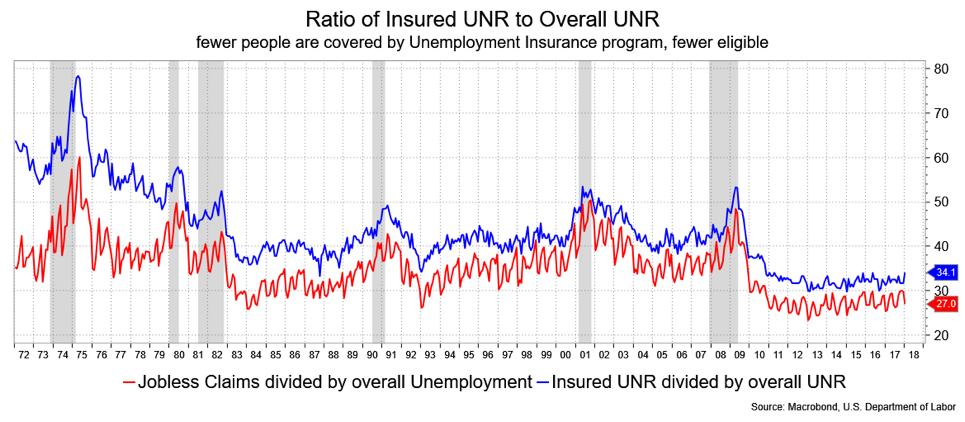

Which brings me to a chart that shows the ratio of the Insured Unemployment Rate to the Overall Unemployment Rate. It’s fallen sharply over the years. Why? Because more working people aren’t eligible since now they’re self-employed, contractors, part-timers, consultants—part of the gig economy. It’s one reason jobless claims overstate the overall health of the economy compared to the past. And the point is that many, or most, of the unemployed aren’t going to receive benefits anyway in the next recession.

Notice how the ratio has risen in the recessions. It could be that they move to gig-style jobs, but retain benefits or that people in gig jobs lose hours and tasks, but retain working status.

The St. Louis Fed recently came out with a piece, “Is the U.S. Due for a Recession?” which at the very least is provocative. The emphasis of the article was using the low unemployment rate as a signal. Sadly, the piece was frustratingly brief and not really conclusive. It notes the UNR hits a low just before a recession, but that seems the chicken and the egg argument. It also mentions that the longer an expansion occurs the closer it gets to tipping over, which seems more egg than chicken. The latter is called “duration dependence.” Included are examples of expansions elsewhere that went on for more years than this one AND noted that the UNR hit 2.5 percent before the recession of 1953.

The broad points are sound, but I didn’t get a conclusion to warn you of an impending recession any more than I did from the Times article, but thought it coincidental that many are talking about a recession but NOT associating such talk to the stock market’s action in the last month. To me, that is more cautionary signal than the length of the recovery or the UNR.

David Ader is Chief Macro Strategist for Informa Financial Intelligence.