By Mark Gilbert

(Bloomberg Gadfly) --As environmental, social and governance issues become embedded in the architecture of money management, the custodians of wealth are discharging the "E" part of their obligations by buying green bonds.

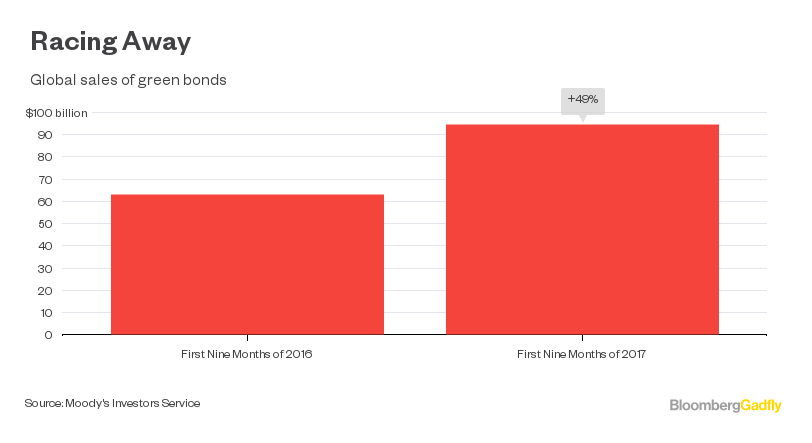

Sales of the securities, which promise to fund environmentally sustainable practices, are booming. Moody's Investors Service reckons issuance is likely to pass $120 billion in 2017 after sales in the first nine months of the year beat 2016's total of $93 billion. Returns on the bonds have outpaced those delivered by conventional investment-grade debt in the past year.

But this shortcut may prove to be an imperfect solution -- albeit the best available in an imperfect world.

The European Commission has just started a consultation process about whether "the duties of institutional investors and asset managers explicitly integrate material environmental, social and governance factors and long term sustainability." In other words, fund managers would have a "fiduciary duty" to consider sustainability when deciding how and where to allocate capital.

But the hurdles facing investors were highlighted in the results of a survey published by BNP Paribas last month: a fifth of investors don't incorporate ESG guidelines into their mandates. The main reason: they can't define them. And almost half of the hold-outs are unlikely to reconsider their position.

Classifying what counts as an ESG-compliant investment is problematic. More than half of the investors surveyed blamed a paucity of reliable data for their not implementing such policies. While that's expected to diminish in the coming years, the lack of tools to analyze the data will then come into play.

More than half of the participants in the BNP Paribas survey said they use green bonds and thematic funds to discharge their ESG responsibilities, beating the percentage using active share ownership, negative stock screening or ESG benchmark indexes.

Even with green bonds, however, there's enough wiggle room to worry an environmentally aware investor. In September, Moody's noted "a variation among issuers relating to ongoing reporting and disclosure commitments." Moody's reviewed 17 bonds and found 10 of them fell short on that score.

Earlier this month, Barclays Plc became the first U.K. bank to issue green bonds designed to fund U.K. assets, selling 500 million euros ($585 million) of the securities. According to ABN Amro, one of the sale managers, the proceeds will be used for "financing and refinancing of those Barclays mortgages on properties situated in England and Wales which are in the top 15 percent of the lowest carbon intensive buildings in these countries, based on estimated energy efficiency."

Since the buildings already exist, refinancing their mortgages -- no matter how environmentally friendly the structures are -- hardly seems like a way for an investor to be meeting its ESG obligations. Nevertheless, the sale attracted bids worth more than three times the amount of debt offered.

Whatever their shortcomings, green bonds are a healthy addition to the investment universe, as long as issuers don't stray into "greenwashing" by mis-allocating the proceeds. It can only be a good thing that asset managers are taking their ESG responsibilities more and more seriously. Here's hoping improved data and better classifications can help with the "S" and the "G" elements in the years ahead.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Gilbert is a Bloomberg Gadfly columnist covering asset management. He previously was a Bloomberg View columnist, and prior to that the London bureau chief for Bloomberg News. He is the author of “Complicit: How Greed and Collusion Made the Credit Crisis Unstoppable.”

To contact the author of this story: Mark Gilbert in London at magilbert@bloomberg.net To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net