By Nir Kaissar

As House and Senate Republicans pursue competing tax overhaul plans, one big disagreement is the estate tax. House Republicans want to repeal it in 2024 while their Senate colleagues want to preserve it.

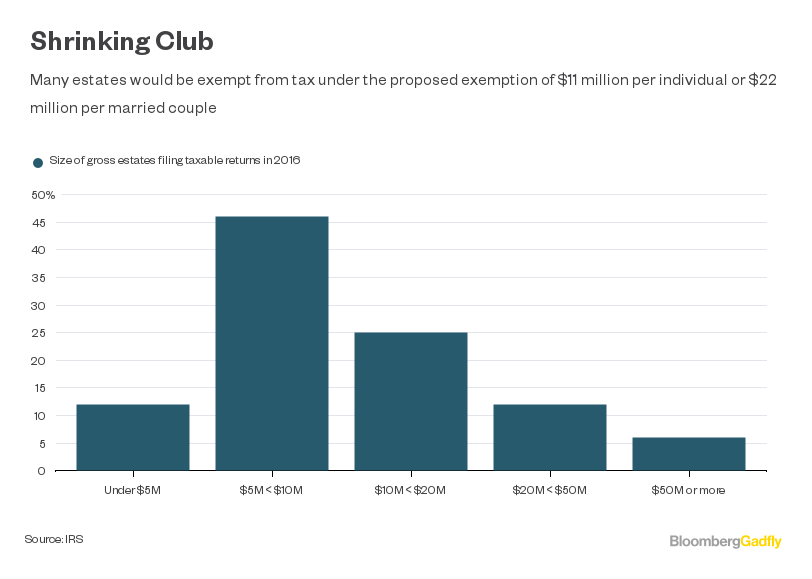

The House’s repeal plan would be a windfall for a small number of the richest Americans. My Bloomberg View colleague Al Hunt notes that the estate tax affects only 0.5 percent of all estates. Both the Senate and House plans would double the estate tax exemption to $11 million from $5.5 million per individual, which would further shrink the percentage of affected estates.

Nevertheless, average Americans dislike the estate tax. A variety of polls over the years have shown that most Americans want to repeal it. Ipsos recently conducted a survey for National Public Radio and found that 65 percent of respondents favor repeal.

That isn’t entirely surprising. The freedom to get rich or die trying -- as Curtis Jackson once put it -- is a cherished American ideal. So it makes sense that most Americans don’t want the government to seize their money, however unlikely it is that they will amass a fortune greater than the estate tax exemption.

But that opposition is misguided. Dynastic wealth erodes democracy, and the estate tax is a useful tool for breaking up fortunes over time. With wealth inequality at the highest level since the Gilded Age, now seems like a particularly bad time to abandon that protection.

There is a consolation prize in the House plan, however. Repeal of the estate tax would open a never-before-available path for average Americans to enrich their heirs. That path is created by repealing the estate tax and preserving the step-up in basis for inherited assets.

Here’s how the step-up works: Let’s say you invest $10,000 in an S&P 500 index fund. Your basis is $10,000. Then let’s also say that investment increases over time to $50,000. You have an unrealized gain of $40,000, on which you would pay tax if you sold the investment. But if you bequeathed that investment instead, your inheritor’s basis would “step up” to $50,000, which means that inheritor would only pay tax if the investment was sold for more than $50,000.

Without the estate tax, the step-up becomes a powerful tool for wealth creation. Let’s say you invest that $10,000 in an S&P 500 index fund at age 30. Around the same time, you have two children, which according to the Pew Research Center is the number of children that a plurality of mothers ages 40 to 44 had in 2014. Your investment grows at the S&P 500’s long-term annual growth rate of 10 percent, including dividends, while long-term inflation approximates the Federal Reserve’s target rate of 2 percent a year.

If you then gave equal parts of that investment to each of your two children when you died at age 79 -- the average life expectancy in the U.S. in 2015 according to the World Bank -- each child would inherit $235,000 in today’s dollars.

Here’s where it becomes interesting. If every generation passed that investment on to the next, each of your four grandchildren would inherit $1.2 million, each of your eight great-grandchildren would inherit $5.9 million, and each of your 16 great-great-grandchildren would inherit a whopping $30 million.

All for doing nothing for 140 years.

Granted, when it comes to investing, nothing is the hardest thing to do. The temptation over those 140 years to raid the investment, or to flee during occasional market panics, or to plunk the money on the latest investment craze would be overwhelming at times. But however difficult, the House plan makes it possible.

I’d still rather have the estate tax. But if it’s repealed, I’m going to squirrel away $10,000 for as long as possible.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Nir Kaissar in New York at [email protected]

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Daniel Niemi at [email protected]