by Shelley Goldberg

(Bloomberg Prophets) --Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen has indicated she will continue to raise interest rates and begin to shrink the balance sheet by buying back Treasuries. Under normal circumstances, this policy should pressure commodity prices downward. Yet that’s not happening.

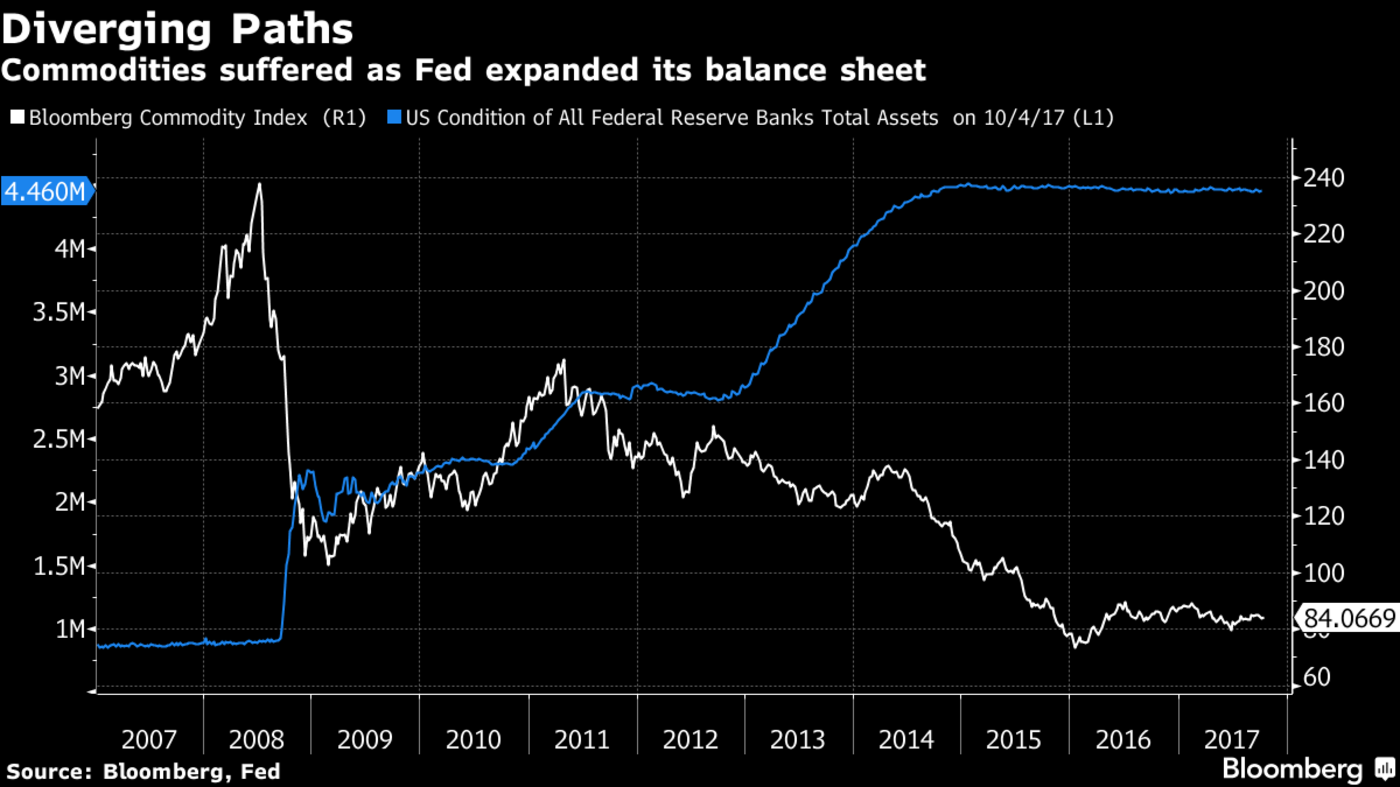

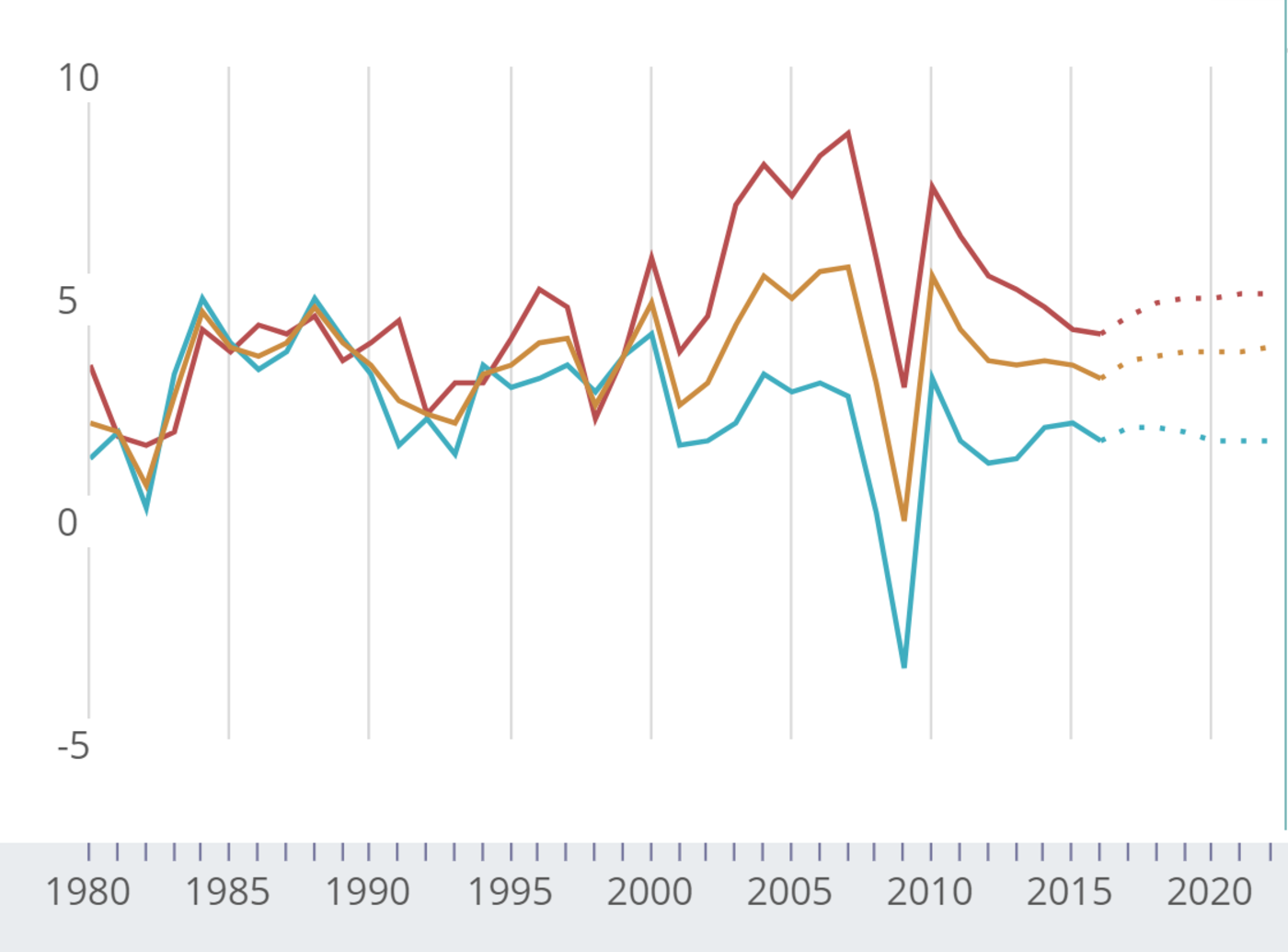

In recent history, the balance sheets of the big four central banks -- the U.S., China, the European Central Bank and Japan -- expanded through easy monetary policy and quantitative easing, as a direct response to the recession of 2007-2009. By 2010, total assets of central banks were $6.5 trillion, with the Fed’s portion at $2.25 trillion. Today, those figures are $18 trillion and $4.5 trillion, respectively. The stimulus resulted in a slower economic recovery compared with historical standards, as measured by global gross domestic product.

While GDP expansion has been slow, global asset growth has been no less than spectacular. In 2010, the global stock market capitalization was $54 trillion; today, it is $87 trillion. This year alone, global equity returns are running 17 percent, about twice the annual rate. U.S. equity markets are reaching all-time highs and fixed-income markets also appear stretched, despite an administration that is showing little success in overhauling the tax code and health care, confronting North Korean and Iranian nuclear threats, handling Asian and NAFTA trade agreements and facing increased domestic terrorism.

Now, central banks are putting on the brakes as a preemptive move on inflation. The Fed plans to reduce its balance sheet from the end of 2017 through 2022, together with more rate hikes. Markets are more aggressively pricing in a November rate hike by the ECB. The Bank of Japan is showing signs of slowing its asset-purchase activity. Only China is cutting.

So while there has been a positive correlation to balance sheets and the equity and fixed-income markets, the reverse holds true for commodities, which didn’t start to show signs of life until mid-June 2017. Until then, commodity prices had lagged behind for years, even in late 2016 into 2017, despite President Donald Trump's rhetoric around infrastructure and a border wall. But just when it was becoming more probable that the Fed was staying steady on the course of rate hikes and the central bank began signaling its readiness to scale back its $4.5 trillion balance sheet, commodities began to rebound, largely driven by crude oil and industrial metals like copper and titanium.

Why the reversal? For one, real wages have been stagnant, not only in the U.S., but in the developed world as a whole. Thus, GDP had been highly dependent on the wealth effect of higher real assets prices to stimulate aggregate demand. In the last eight years, the recovery in measured inflation of goods and services has been slow while asset prices (equity and fixed income) have inflated.

Second, commodities as an asset class have been passed over in favor of traditional markets. Investors weren’t seeking diversification because they felt safe sitting in broad-based indices. Traditional market long-only vehicles came back in vogue, while alternative investments, like commodities and the hedge funds and systematic traders that invested in them, lost favor (their fees relative to returns weren’t justified, and volatility in the commodities markets was not sufficient to make decent returns).

Third, monetary policy today is driven less by debt and more by exchange rates. Despite a significant increase in the Fed’s total assets since 2007, the bank has maintained a fairly constant balance sheet since 2014. What has changed is its composition. The Fed bought Treasuries, now totaling $2.46 trillion, and mortgage-backed securities valued at $1.78 trillion.

As the U.S. and developed economies approach the end of their long-term debt cycles, their interest rates, while rising, are still low. The dollar tends to rally on expectations of higher rates. Commodity prices, inversely correlated to the dollar, have suffered amid the greenback’s strength, as markets already factored in more rate hikes.

Fourth, the People's Bank of China cut the required reserve ratio on Sept. 30 to alleviate pressure caused by recent deleveraging and controls on growth. While easing makes the PBOC the outlier among central banks, China has evolved to become the world’s largest consumer and producer of global commodities and thus has more influence on prices than any other nation. And that influence is likely to grow.

Nevertheless, timing is key. Central banks are putting on the brakes even as commodities are enjoying good support. Yet, there are no promises of a smooth ride. Rate hikes and Treasury purchases must be precisely timed and implemented in the coming months to prevent major market disruptions. On Oct. 11, the minutes of the September FOMC meeting are due, though they will likely prove little different from those of July.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shelley Goldberg is an investment adviser and environmental sustainability consultant. She has worked as a commodities strategist for Brevan Howard Asset Management and Roubini Global Economics.

To contact the author of this story: Shelley Goldberg at [email protected] contact the editor responsible for this story: Max Berley at [email protected]

For more columns from Bloomberg View, visit Bloomberg view