By John Gittelsohn and Sonali Basak

(Bloomberg) --It was an unusual Wall Street formula.

Take the Los Angeles Dodgers. Add NBA Hall-of-Famer Magic Johnson. And stir in Guggenheim, one of the grand old names of American business.

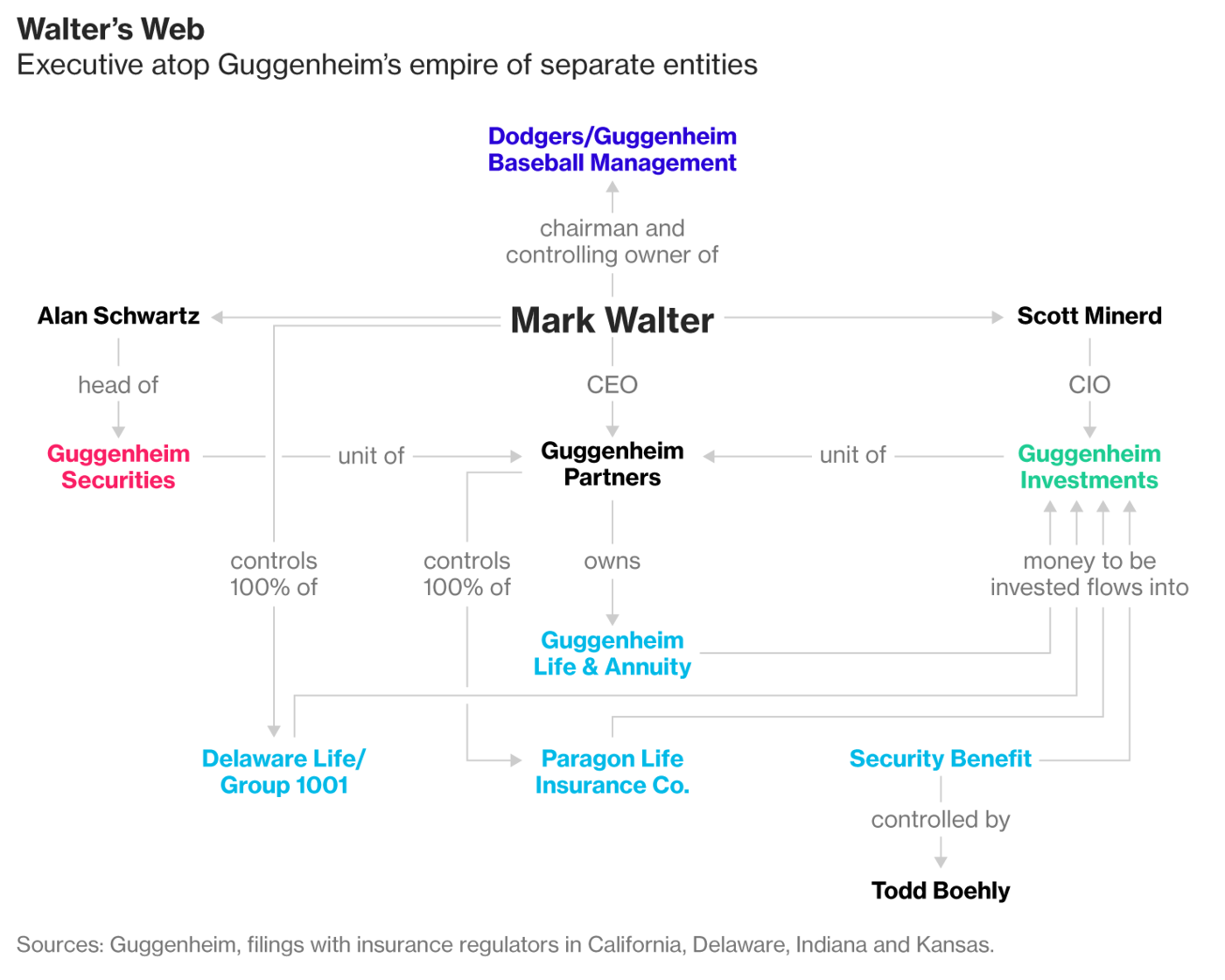

Today the 2012 Dodgers takeover seems to encapsulate the growing trouble inside Guggenheim Partners, whose leader, Mark Walter, cut that winning side deal for himself and select colleagues.

Interviews with more than a dozen current and former employees and people close to the firm paint a portrait of a once-thriving partnership now riven by personal and professional rivalries.

No fewer than 60 bankers, traders and analysts have departed over the last two years. Guggenheim recently went so far as to offer some senior managers bonuses to stay on for at least a year amid frustration over money, management style and personnel.

Top executives aren’t just feuding over the CEO’s outside investments, according to the current and former employees. They’re upset about the direction of the firm, which lost value last year even as assets grew. They’re also at odds over the promotion, pushed by Walter, of Alexandra Court to oversee global institutional client relations despite her lack of Finra credentials for the post.

Meantime, Court is negotiating an exit, these people say. Some Guggenheim employees wonder how long Walter, 57, will remain CEO.

The conflict reached a boil in late July, when Scott Minerd, Guggenheim’s star money manager, confronted Walter in the firm’s Chicago office.

The flashpoint: Walter’s decision to promote the South African-born Court even though she lacked key securities accreditations, including a basic U.S. Series 7 license. Guggenheim fired almost two dozen workers in her unit when she took the job.

Unsettled Clients

Minerd, a 57-year-old body-builder with a reputation for a volatile temper, told Walter that the move had unsettled employees and clients, said people familiar with the matter. Some of the people said Court received preferential treatment because of her close relationship with Walter.

Court’s attorney, Martin Singer, said her promotion had nothing to do with favoritism, but stemmed from her successful record building Guggenheim’s European business since 2010. She has brought “a disciplined, professional and efficient infrastructure” and has raised $20 billion of new assets since her April 2016 appointment to her current job, according to Singer, whose celebrity clients have included Bill Cosby, Charlie Sheen and Scarlett Johansson.

Unusual Step

Michael Sitrick, a Los Angeles-based public-relations executive representing Guggenheim, said of Walter and Court:

“There is no non-business relationship. But if there were, it was fully and promptly disclosed to the appropriate parties at Guggenheim, in accordance with established processes and procedures, which were then fully implemented, to avoid improper influence or favor.”

Court’s promotion was supported by senior management, Sitrick said. But in a January memo addressed to portfolio managers and senior executives and seen by Bloomberg, Walter called resistance to Court’s authority “pervasive” and “insubordinate.”

With tension rising, and word of the turmoil leaking out, Guggenheim’s board took the unusual step of issuing a firm-wide memo on Sept. 20.

“We issue this -- a unanimous statement of Guggenheim’s Board -- to set the record straight,” the memo said. The board “affirms full and complete support” for Walter and Minerd.

The memo continued: “The firm is thriving, growing, stable and strong.”

Walter, Minerd, Court and other Guggenheim executives declined to comment for this story.

It’s safe to say this isn’t quite what the Guggenheims had it mind when the family began assembling a cast of Wall Street characters to capitalize on a name that rivals Carnegie and Rockefeller.

Meyer Guggenheim

Meyer Guggenheim arrived in the U.S. in 1848 and made his fortune in mining and smelting. One of his seven sons, Benjamin, went down with the Titanic. Another built the art collection that gave rise to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan.

Today, a Guggenheim descendant, Peter Lawson-Johnston II, sits on the board of Guggenheim Partners. Among Guggenheim’s key hires: Alan Schwartz, the dealmaker who headed Bear Stearns Cos. as it ran aground in 2008.

Nowadays the real money behind Guggenheim is linked to another, less famous family: Sammons. Dallas-based Sammons Enterprises, which is now owned by its employees and has $85 billion in assets, holds about one-third of Guggenheim’s voting shares. Sammons initially bought into Liberty Hampshire Co., a financial firm that Walter had founded and later folded into Guggenheim.

Despite enviable successes, the rival camps have formed. Those allied with Walter have complained they’re carrying weight for Minerd. Revenue at Minerd’s asset-management unit fell 5 percent last year, contributing to a firm-wide 4 percent loss for shareholders, according to a June 30 letter to investors seen by Bloomberg. Minerd’s camp blamed Court’s management for the revenue drop, according to current and former employees. Minerd’s three largest mutual funds have bested about 95 percent of their peers over five years, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Senior Management

Schwartz, for his part, has built Guggenheim Securities and snapped up M&A talent. Revenue at his investment-banking unit rose 13 percent in 2016, to $580 million, according to the shareholder letter.

But the firm’s business isn’t the only game at Guggenheim. Over the years, Walter and others have pursued side deals, sometimes bankrolled, at times controversially, by Guggenheim’s various insurance affiliates.

Under Fire

Take the Dodgers deal. To create Guggenheim Baseball Management, the entity that bought the baseball team, Walter assembled former Los Angeles Laker Johnson, Guggenheim’s then-president and co-founder Todd Boehly and Texas oil tycoon Bobby Patton. Minerd, Schwartz and Lawson-Johnston weren’t named as partners. (Spokesmen for Johnson and Patton declined to comment.) The transaction came under fire when Guggenheim and three insurance affiliates were sued by clients for conflict of interest.

The lawsuit claimed that Guggenheim executives saddled the insurers with risky, illiquid assets, including the Dodgers, and that they inflated assets to get the deal done. The 105-page suit, filed in Chicago federal court, was voluntarily dismissed within 24 hours. It was withdrawn and never refiled “because it was recognized that the allegations had no merit,” Sitrick said.

The next year, in an unrelated matter, Guggenheim agreed to pay $20 million, without admitting wrongdoing, to settle claims with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The issue centered on a $50 million loan that a senior Guggenheim executive had received from a client, which might have raised conflicts of interest if the firm subsequently favored that client.

The executive, according to four people familiar with the matter, was Boehly. The client was Michael Milken, the one-time junk bond king, the people said. Spokesmen for Boehly and Milken declined to comment.

Boehly’s Exit

Boehly, 44, soon left Guggenheim to start a private investment firm, Eldridge Industries. Walter has told at least one business associate that he, too, would like to reach for something bigger.

He’s certainly been busy. In 2013, he and his wife, Kimbra, bought White Oak Plantation, a 7,400-acre Florida refuge for rhinos, giraffes and other animals. In 2016, Boehly divested his stake in another insurance affiliate, Delaware Life Insurance Co., with $37 billion in assets, and handed control to Walter. Delaware Life has since been rebranded as Group One Thousand One. Daniel Towriss, Guggenheim’s insurance expert, was named CEO in September.

Private Investment

That’s not all. In January, Walter announced plans to open a $1 billion “private-investment platform” with Frank McCourt, the previous owner of the Dodgers. And in May, he joined a partnership that paid $85 million for entertainment mogul David Geffen’s seaside estate in Malibu, California.

In July, Guggenheim brought in Jerry Miller, a former Deutsche Bank AG executive, to help broker peace between factions. Late last month, it announced it was selling its exchange-traded funds business for $1.2 billion, which will give the firm additional capital.

A day before Guggenheim’s board issued its September memo, and with speculation swirling inside the firm, Minerd went on CNBC. He said Walter had given no indication that he wanted to leave Guggenheim.

Minerd added: “All of us have to make a decision someday about what our lives are and where we’re going.”

--With assistance from Scott Soshnick, Hannah Levitt and Tom Metcalf.To contact the reporters on this story: John Gittelsohn in Los Angeles at [email protected] ;Sonali Basak in New York at [email protected] To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Gillen at [email protected] Bob Ivry, Josh Friedman