When markets sank in 2008, target-date funds disappointed their shareholders. During the third quarter of the year, the average target fund lost 10 percent, while the S&P 500 declined 8.4 percent, according to Ibbotson Associates.

The losses were particularly shocking because target-date funds were marketed as safe choices that always kept some of their assets in bonds. Many employers had encouraged 401(k) plan participants to use target funds. Worried that problems in target funds could undermine retirement plans, Congressional critics called for investigations.

Should target funds be changed? Fund companies are divided on the issue. Companies such as T. Rowe Price see no reason to redesign their funds. But other fund marketers have moved to lower the risks in their target portfolios. Those making alterations recently include Alliance Bernstein, Invesco, and Putnam Investments.

Target funds are designed for investors who will retire in certain years, such as 2020 or 2035. The fund portfolios are broadly diversified, holding stocks and bonds. As the retirement date approaches, the portfolio allocation shifts to become more conservative, including heavier stakes in fixed income.

Not For Me, Thanks

Most advisors have remained cool to target funds. “For someone who doesn't know anything about investing, the target funds are better than a blind shot in the dark,” says John Sterba, president of Investment Management Advisors, a registered investment advisor in New York. “But the problem is that the funds are one-size-fits-all. They are not customized to suit the needs of particular clients.”

Despite their limitations, the target funds are likely to remain a growing force in the investment world. Assets in the funds have climbed from $9 billion in 2000 to more than $250 billion today. The growth is likely to continue as more employers add target funds to retirement plans.

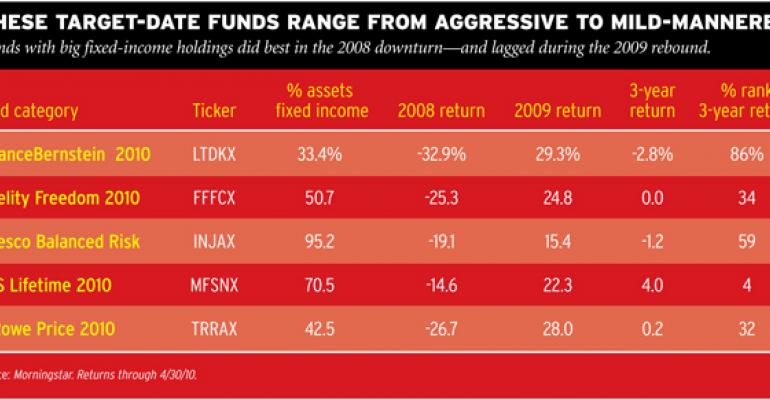

The debate about target funds centers on the question of asset allocation. T. Rowe Price has taken the position that savers need to have big stakes in equities in order to support lengthy retirements. As a result, the company's target funds rank among the industry's most aggressive. T. Rowe Price Retirement 2010 has about 57 percent of its assets in equities and the rest in fixed income. In contrast, the average fund with a similar retirement date has about 41 percent of assets in equities, according to Morningstar.

The T. Rowe Price approach clearly has merits for investors who need growth. During the five years ending in April, T. Rowe Price 2010 returned 5.4 percent annually, outdoing 98 percent of competitors. But the aggressive asset allocation comes with risks. In the downturn of 2008, the fund lost 26.7 percent, trailing 69 percent of competitors.

Investors who seek a cautious choice may feel more comfortable with Invesco's funds. Unsatisfied with the risks of equity-heavy portfolios, the company retooled its target funds. Now Invesco Balanced-Risk Retirement Funds normally keep about 90 percent of assets in bonds, 30 percent in stocks, and 30 percent in commodities. The numbers add up to more than 100 percent because the portfolios hold futures, which can be leveraged to increase the total exposure to each asset class.

Invesco's allocation is markedly different from most target funds, which stick with familiar mixes of stocks and bonds. The company settled on the innovative approach after studying various investment scenarios. The Invesco researchers concluded that there are three main market environments: periods of recession, growth with low inflation, and growth with high inflation. While stocks excel during times of noninflationary growth, bonds lead in recessions, and commodities do best when growth is accompanied by inflation.

By holding assets in the three different asset classes, the funds are likely to deliver decent results in most environments, says Scott Wolle, the Invesco portfolio manager. “Nobody really knows what will happen over the next few years,” Wolle says. “In a world of uncertainty, it makes sense to hedge against different economic outcomes.”

Wolle concedes that his funds will likely lag during bull markets. But he argues that by avoiding big losses in downturns, Invesco should deliver decent results over the long term.

Aggressive? Some Are

AllianceBernstein has taken a very different route to managing risk. The company's target funds have long ranked among the most aggressive. AllianceBernstein 2010 Retirement Strategy has about 63 percent of assets in equities, well above the category average. But after the downturn of 2008, AllianceBernstein began looking for ways to limit volatility.

The company's researchers rejected the idea of increasing the strategic bond allocation because that would lower expected long-term returns. AllianceBernstein finally decided to employ short-term measures that can steady portfolios. “We wanted to provide smoother results during periods when it is difficult for people to stay invested in the markets,” says Tom Fontaine, head of defined contribution investments for AllianceBernstein.

To protect retirees and those close to retirement, the company divides portfolios. Up to 20 percent of assets are set aside in a volatility management component. The rest of assets remain invested according to the strategic allocation. During times when volatility is low and the outlook for stocks remains promising, all the assets in the volatility component will be invested in stocks. But as volatility increases, the assets will gradually shift to fixed income. “Think of the volatility component as shock absorbers on a car,” says Fontaine.

When volatility dropped early this year, the AllianceBernstein fund had all the volatility component invested in stocks. Fontaine says that the component will be all in bonds if volatility returns to the severe levels of 2008. He says that the volatility component should reduce losses in downturns. But he concedes that the investment could trail as markets rebound.

It is too soon to tell whether the approaches developed by AllianceBernstein and other companies will prove to be winners over the long term. But it seems likely that these will not be the last shifts in target funds. Most funds are less than a decade old, and managers are still struggling to find the right formulas.