By Patrick Clark

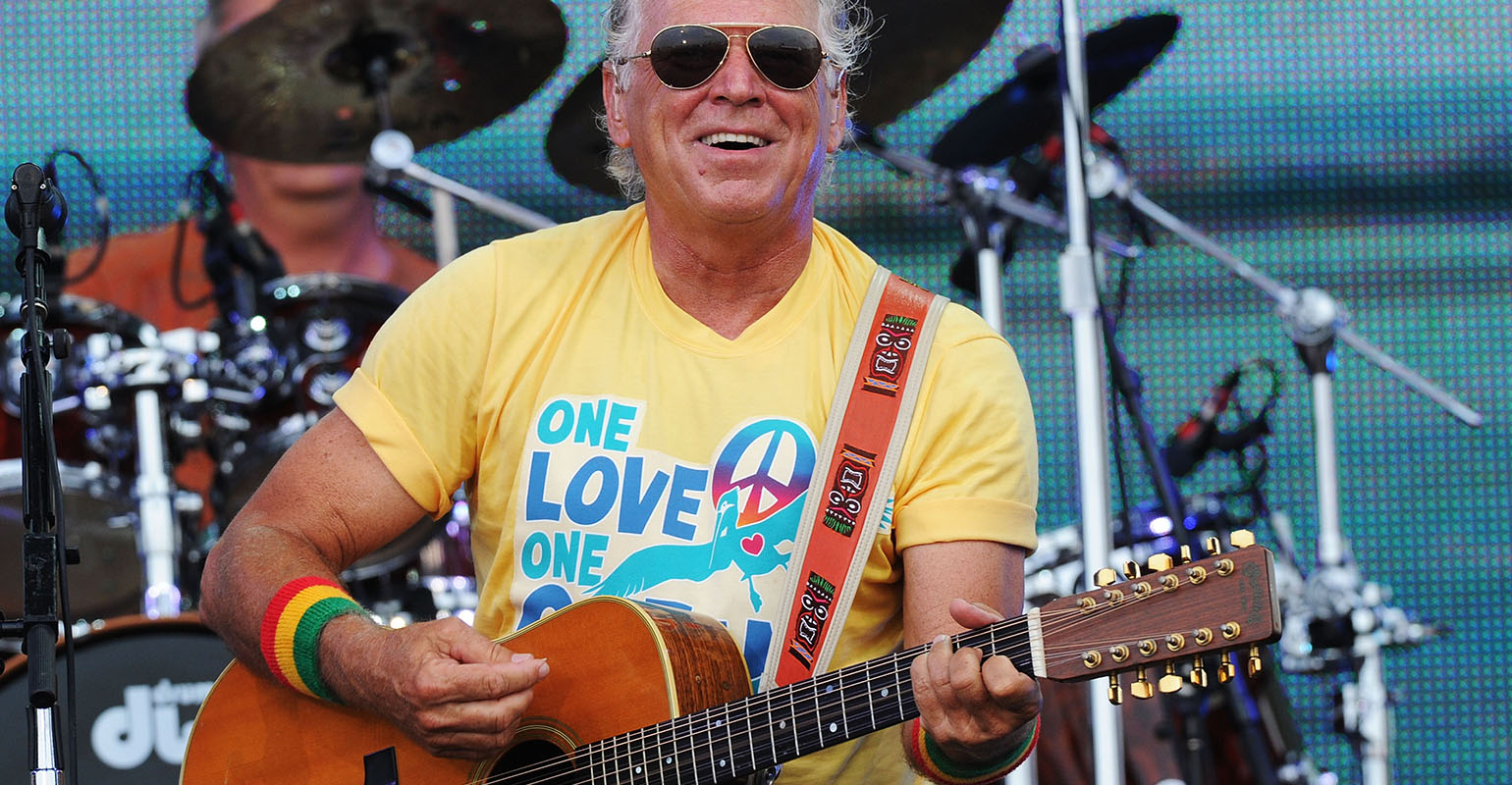

(Bloomberg) --Joe Lombardi strolled through the packed Field 5 parking lot outside the Jones Beach amphitheater on Long Island—past the men dressed as pirates, the boat parked atop a party bus, the cornhole players and the silver-haired tailgaters pedaling tandem bikes. The diehards had arrived at dawn, and by mid-afternoon, some had crashed out in the shade of inflatable palm trees, napping away the hours before Jimmy Buffett would take the stage.

“A certain segment of his fans would like to live in Margaritaville,” said Lombardi, who serves as president the local chapter of the Parrot Heads in Paradise, a Buffett fan club with 25,000 members around the world.

It wasn’t an idle observation. Over the last two decades, Buffett has built a licensing and hospitality empire on the back of his most ubiquitous hit, selling everything from hotel rooms to deck chairs and frozen shrimp through his company, Margaritaville Holdings.

Now he’s slapping his brand on 55-and-older communities in a novel bid sell homes to boomers who are ready to kick back—just not in the same way their parents did. In February, the company said it was partnering with a Canadian homebuilder called Minto Communites to build 7,000 homes in Daytona Beach, Florida, in an age-restricted development called Latitude Margaritaville.

Buffett has a loyal fan and consumer base, but aging home buyers may prove a tricky market. Boomers are working longer and moving less than their parents, preferring to renovate their homes so they can age in place. For some, the snowbird lifestyle their parents’ generation invented might look like one last tradition against which to rebel. Others might just not want to admit they’re getting old.

“We have people who are really into the lifestyle. They can’t wait,” said Lombardi. Other fans worry the communities could resemble theme parks, or worse: “The last thing anyone wants is to go someplace where people are living out their last years.”

Forty years ago, long before it became a microwave dinner or real-estate development, “Margaritaville” was a 1977 hit that saw Buffett playing his trademark role of everyman in paradise, bemused at his circumstances but determined to live in the present, cocktail in hand, not dwell on the half-remembered past.

Buffett turned Margaritaville into an actual place with the opening of his first restaurant in Key West in 1987, but it wasn’t until the late-’90s that he kicked his branding operation into gear. Today, the singer’s website offers an astounding array of branded consumer goods, including LandShark Lager, rum and tequila, chips and salsa, pool floats, beachwear, and a selection of souped-up blenders sold under the heading of party machines.

Margaritaville’s hospitality business has become an even bigger draw, with 70 restaurants and a string of hotels in resort towns dotting the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. In all, its sales topped $1.5 billion in revenue in 2015, and more than 20 million guests walked into a Margaritaville establishment last year, according to John Cohlan, the company’s CEO.

Even so, the brand’s expansion into real estate shouldn’t have been a surprise. “Twenty years ago, if you had asked me what’s the logical, highest, and best use of the IP, I wouldn’t have said restaurants,” said Cohlan. “I would have said a place to live.”

For Cohlan, that can mean a hotel room to stay in a few nights or a cottage to visit a few times a year. Yet Latitude Margaritaville may be the brand’s true apotheosis.

Buffett’s songs, from “A Pirate Looks at Forty” (1974) to “Oldest Surfer On the Beach” (2013), have long concerned themselves with aging gracefully. Buffett himself is 70. His fan base is getting up there, too. Little wonder that the largest chapter of the Parrot Heads in Paradise, with more than 1,000 members, is in The Villages, a sprawling 55-and-older (“55-and-better,” in industry parlance) community in central Florida.

That tantalizing alignment of brand and product helps explain why news of the first Latitude Margaritaville generated a lot more interest than the typical retirement community. Stephen Colbert and Jimmy Kimmel picked up on the announcement; on Good Morning America, Michael Strahan wondered if he were old enough to move in.

More than 100,000 people signed up for updates on the project, according to Mike Belmont, president of Minto Communities USA. (That prompted the developer to move forward with a second Latitude Margaritaville, in Hilton Head, South Carolina, and a marina condo project—named for the 1983 Buffett tune “One Particular Harbour”—near Sarasota, Florida.) While the first homes won’t be ready until next year, in October, prospective buyers can visit a sales center in Daytona Beach to see what’s in store.

“What we try to do is create emotional triggers that transport you to Margaritaville,” said Pat McBride, whose firm has been designing Buffett’s restaurants and resorts for nearly 20 years. Taking his cue from Buffett’s 1979 song “Volcano,” he installed tequila-and-sour-mix-spewing mountains in some early restaurants. A 14-foot-tall blue flip-flop and a chandelier made of margarita glasses remind guests at the Hollywood, Fla., resort why they’re there.

Diners linger just a few hours, hotel guests a few days; a place where people live full-time calls for a lighter touch. In Daytona Beach, a faux lifeguard station will stand sentry at the entrance; the place will be planted with dense, tropical vegetation. The plans also call for a town center built around a series of connected swimming pools, pickle-ball courts, and a bandshell, plus a doggie spa called Barkaritaville and a mechanic shop that will specialize in customizing tricked-out golf carts.

The Margaritaville team is also creating programming inspired by Buffett’s interests—things like fly-fishing classes, cooking lessons, and live music. The idea, said McBride, is to give boomers a chance to pick up the pursuits they’d put on hold decades earlier in order to grow up and get jobs. Or as Cohlan puts it: “We like to talk about it as going back to summer camp at 55.”

It’s a sensible approach. For decades, developers sold retirement homes on golf courses and sunny climes. As boomers age, however, the market is diversifying, and builders are ditching one-size-fits-all designs to target narrower groups.

That means projects centered on activities like community service, agriculture, and wellness, said Margaret Wylde, chief executive of ProMatura Group, a research and advisory firm focused on older consumers.

But selling homes by signaling to a niche group cuts two ways, attracting some while warning others to stay away. You don’t retire to a dude ranch if you don’t like the smell of manure. You probably don’t buy a home in Latitude Margaritaville if you don’t think you’ll fit in with Buffett fans.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love to party,” Wylde said. “The crowd I imagine being attracted is not my crowd. It would not be something that would attract me.”

Joe Lombardi didn’t really consider himself a fan when he went to his first Jimmy Buffett concert in 1986, at the Jones Beach stop on his Floridays tour—but then Buffett started singing, and so, it seemed, did everyone in the stands. In the years since, Lombardi has seen Buffett more than 70 times, and spent countless hours doling out concert tickets and organizing his club’s charity events.

Maybe it’s that sense of belonging that’s helped Buffett’s fans wryly stomach the recognition that their idol is always selling them something. They don’t mind being suckers for the brand, because they’re having fun.

“We joke about how soon he’ll be selling us Margaritaville Depends or LandShark Ensure,” said Larry DeGennaro, 57, a longtime parrot head who’d made his annual pilgrimage to Buffett’s Jones Beach from his home in Pearl River, N.Y. Sure, it’s silly to buy a house, or even a deck chair, because a singer’s name is on it, but Buffett fans tend to give in to the pull. “We all want to live vicariously through him.”

DeGennaro and his wife Denise own a townhouse in Hilton Head, and in the weeks before the Jones Beach show they’d driven around the site of the future Latitude Margaritaville. Denise, 57, was showing off photos of the development site to a friend, Michelle Moffitt, when a group of younger women interrupted, looking for “the guy with the shot stick.”

You mean the “shot ski,” the parrot heads corrected, describing a tailgating innovation consisting of four shot glasses affixed to a ski, allowing a group of friends to throw back shots at once. (The guy with it wasn’t around; the women moved on.)

Moffitt, 60, usually catches Buffett at least once when he passes through the Northeast each summer. She’d come to Jones Beach this time from Saratoga Springs, a good three hours north, but she too was thinking about a Margaritaville home where she’d relax by a pool to the soothing sounds of tropical rock and roll. “My kids were like, ‘Mom, go there.’”

To contact the author of this story: Patrick Clark in New York at [email protected] To contact the editor responsible for this story: Samantha Schulz at [email protected]