The world’s wealthiest family offices are looking to help clients use their money to effect positive change in the world, but for many there are still disconnects, often generational, between intention and action.

UBS' recently released 2017 Global Family Office Report, which surveyed 262 family offices of various types worldwide on an exhaustive variety of subjects, reveals that family offices are increasingly engaged in philanthropy and social and environmental impact endeavors.

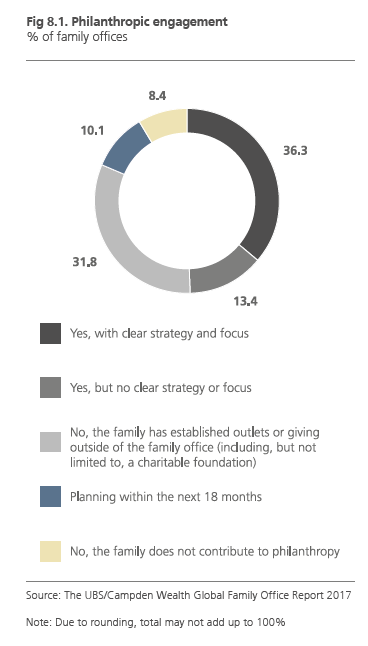

Overall, some 60 percent of surveyed family offices either currently manage families’ philanthropic activities or plan to do so within the next 18 months. Of those, almost 95 percent plan to either maintain or increase their current philanthropic commitments within the next year.

In total, the average respondent donates $5.7 million annually to charitable causes, though this number is notably dragged down by the Asia-Pacific region, which donates, on average, only $600K—in comparison, North America weighs in at $8.4 million and Europe $6.7 million. That the average family office surveyed had about $921 million in assets under management, should give an indication of how much room for growth there still remains in this area, and the scale of the potential impact of even a single percentage point increases in these numbers. Both the reasons for optimism, as well as just how far many family offices have to go, are reflected in this quote from an anonymous single-family office executive:

“About four or five years ago, we developed a mission and have since been trained to be increasingly focused and strategic around donations, which is still a work in progress. We recently hired an executive director dedicated to our giving. So we now have a separate foundation that meets quarterly, an executive director, a mission—and we are now working to improve the quality of our granting process.”

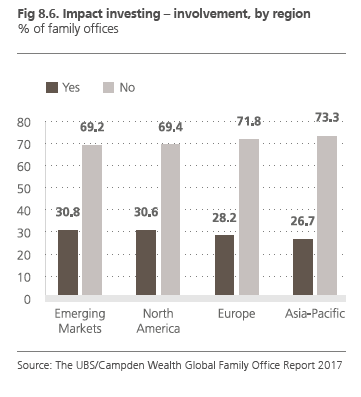

In a similar vein, 28 percent of respondents claim to be currently engaged in impact and/or ESG investing, and roughly 40 percent overall are expecting to increase their allocations to such opportunities. However, not all is going quite as smoothly as advertised in this area. The survey notes that though the numbers look rosy, “as we probed further through qualitative interviews, a number of family offices alluded to the fact that most of them did not understand how to implement impact investments, while a separate cohort did not believe in mixing business with philanthropic endeavors.”

The struggles of these groups, and the generational conflict they can create, are reflected by a different executive, who explains, “We don’t currently engage in impact investment. Let’s do the best job we can at making money. Then that gives us more money and resources to give. But that may be old thinking. And I suspect that we may look at that a little more over the next few years. The next generation cares more and more about social-impact investing and how we invest.”

And that generational shift is bearing down fast. Creating a succession plan is the surveyed families’ top priority—69 percent expect to undergo a generational transition in the next 15 years. Interestingly, there’s a fairly clear-cut divide in how these families plan on handling that incoming transition of power. Nearly 36 percent expect to follow the “traditional” path and have the next generation directly take over the family office. However, almost 31 percent are planning on handing the reins over to a nonfamily professional, with the next generation simply providing occasional oversight, a route that even only a decade ago was still somewhat sacrosanct.

Ultimately, facilitating the transfer of intergenerational wealth is the primary purpose of most family offices, and family offices seem to be taking an increasingly outward view, both in terms of who will manage that wealth on a day-to-day basis and to what aims it will be put.